Now that Michael’s given us an overview of the Mormon priesthood and answered some of my questions about how the priesthood relates to gender and transfiguration of spirit, I think we’ve all got enough background to go on to weirder and wonkier questions. Again, my questions are in bold, his answers follow, and he’s not to be blamed for the illustrations.

Q: At various points in the history of Christianity, monks and ascetics were seen as particularly holy because they withdrew themselves from the world, contemplating only God. Is there any Mormon analogue to this role? Has there been a kinda-gnostic tradition in Mormonism that saw the material world as evil/dangerous?

There has never been a monastic tradition in the LDS Church. The closest you would get is a mission, wherein your time and energies are strictly regulated to make the most of your time proselytizing. Or maybe that time when all the Mormons removed themselves to the Mountain West, lived in a quasi-theocracy, and followed a system of collective economics (only somewhat kidding!).

And as to a gnostic tradition – I don’t think there’s been anything like that. In fact, one of Joseph Smith’s pronouncements – canonized in scripture – is that matter and spirit are the same substance, just that the latter is “purer” (don’t ask me what that means, exactly). In the same vein, we believe that God the Father and Jesus Christ (two separate beings!) have physical bodies, and that one of the primary purposes for human beings’ life on earth is to obtain bodies, like the one God has, that can be resurrected and kept eternally. We also believe that matter cannot be created nor destroyed, and that God’s creation of the universe was really molding it out of “matter unorganized” through whatever means you believe in (the LDS Church has no position on evolution). No creation ex nihilo here, but that’s another matter.

Of course, that does not mean that Mormons have not seen the political world as evil/dangerous. After having been driven out of at least multiple settlements with pitchfork, torch, and rifle close behind, being pursued to their desert sanctuary by federal troops, and being systematically disenfranchised, dispossessed, and discriminated against, I believe most people would come to feel that way. Nevertheless, even though the Mormon leadership in the 1800s was often at odds with American politics at large (and often downright derogatory toward American culture, but the feeling was mutual), they never turned their backs on the founding documents of the nation. Mormon Constitutionalism is very long-lifed, dating back to when in a revelation to Joseph Smith God implied that the American founders were inspired by Him to establish those documents. How literally is this to be taken? Your mileage may vary.

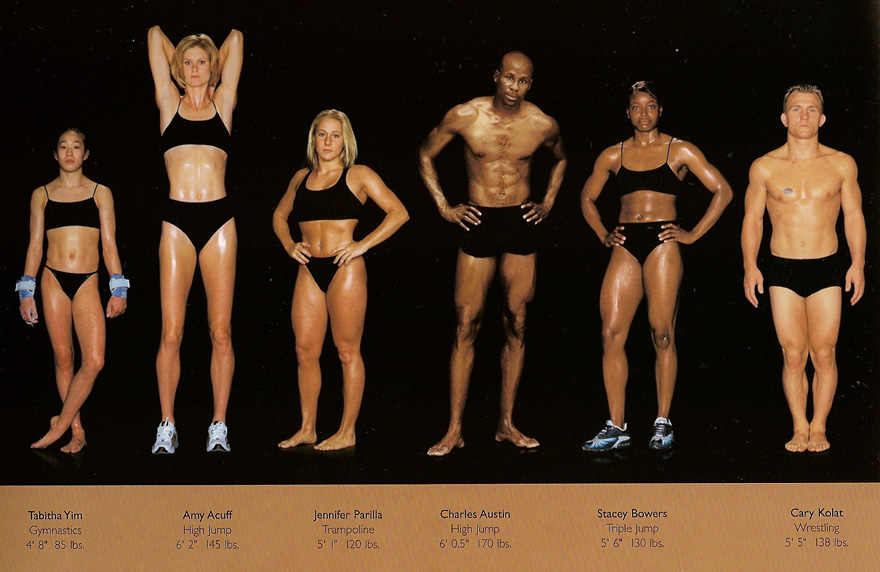

Q: So, as the transhumanist, I’ve got to ask what does “one of the primary purposes for human beings’ life on earth is to obtain bodies” imply about how we treat them, how we’re allowed to modify them? I know you’re a scifi nerd, too, so are there any possible futures you see as in direct contravention of the correct attitude to the body?

Wow! James Cameron goes to Challenger Deep, and this question may as well be named just that.

I think that first is that we should not try to slough off or diminish our sense of embodiment. This principle formed the basic idea of a recent talk (Mormonspeak “sermon”) by apostle David A. Bednar (entitled “Things As They Really Are”), in which he cautioned against forgoing physical human contact for digital communication of whatever means. His point was that by ignoring our bodies, we move toward restoring ourselves to a premortal, pre-embodied state: we, in effect, regress to a previous, lower state of being. There are some things we can only learn and hone with bodies (among them the challenges of health, physicality, limitation, and imperfect communication). Moreover, just as the spirit is tried during its time on Earth, the body must be tried as well; both must be redeemed through the Atonement of Jesus Christ.

The Book of Mormon prophet Lehi had this to say, and I think it’s very pertinent to the LDS conception of physical bodies:

“For it must needs be, that there is an opposition in all things. If not so, my first-born in the wilderness, righteousness could not be brought to pass, neither wickedness, neither holiness nor misery, neither good nor bad. Wherefore, all things must needs be a compound in one; wherefore, if it should be one body it must needs remain as dead, having no life neither death, nor corruption nor incorruption, happiness nor misery, neither sense nor insensibility.”

We need both health and sickness to understand God and to become like Him. (There’s a lot more to this, but that gets off into the LDS conception of God, about which books on books have been written…)

In addition, the LDS Church, with Paul, teaches that the body is the temple of the Holy Spirit. Some types of body modification, such as tattoos and other permanent alterations that lead to (dare I say?) an “unnatural” appearance, are thereby discouraged. Nevertheless, we are not expected to accept everything that comes our way; my mother had plastic surgery to reconstruct what she had lost in a double mastectomy. I can’t say there’s an easy answer. It’s similar with the question of diminishing one’s connection to the body: how much, for example, should we try to mitigate pain, illness, and old age? I can’t say that I’ve thought too much about that subject.

The only futures I can project at present that would for certain controvert the Mormon idea of the body would be ones wherein the experience of embodiment is totally discarded. Maybe it’s something like the Matrix or the real-life Second Life of Surrogates, or perhaps it’s human brain functions converted into computer code. That’s the extreme, though; there’s a lot of gray in the middle. I don’t know how I would feel about deliberately replacing functional limbs with souped-up prosthetics, for example, though I’d probably come down against it. (This is where consulting the Mormon theologians and philosophers would come in handy. They’re thought a LOT more about embodiment than I have.)

On another note, I have no problem understanding the natural biases and heuristics of the human body, because it helps me think better about why I think and do things. I’ve even told people that I believe that sometimes God takes advantage of our natural thought processes to help us act properly.

Q: Are there ever times you wish your church had permanent clerics? Or advantages of that system you’d like to incorporate a different way?

There are benefits and disadvantages to both. One benefit of having a professional clergy would be that after going to grad school in Mormon Studies I might get a job! But alas, that is not to be.

One thing that I believe would come out of an organized clergy would be a byproduct of the training needed to get there: an LDS Church with a more systematic and well-defined theology, with theologians to elaborate it. As it stands, Mormon theology is a hobby for those with an interest in it (and some of those hobbyists are very good), while the Church mostly busies itself with trying to help its members live in a Christian fashion. Indeed, much of the confusion in popular culture concerning Mormon beliefs – as well as the sometimes stunning heterogeneity of popular Mormon belief once you venture beyond the core doctrines – comes from the large number of pronouncements by historical LDS leaders, many just speculating, that have never been officially refuted by subsequent leaders. The preferred policy is just to let peripheral matters fade into quiescence. While it would be nice if the Church came out and denounced some things (like past racist policies) outright, there’s also a part of me that loves the open, exploratory, undefined nature of LDS belief. I’m often glad there’s no LDS Aquinas.

On the other hand, another benefit might be better training among leaders. With an ever-changing leadership, leaders find themselves in positions for which they are utterly unprepared. If you were a young auto mechanic called as bishop, how would you counsel a woman who approaches you with concerns of faith that orbit obscure historical facts you’ve never heard of? If you’re a lawyer, how do you teach 5-year-olds about the New Testament? Sometimes the fruit of inexperience can verge on disastrous. However, the lay ministry and the mutability of callings are very horizontal forces in an otherwise very vertical hierarchy; besides, where else could the abovementioned people get those sorts of life experiences? Much of the beauty of the lay ministry resides in how violently it forces us into contact with our fellow men and women in cooperation toward common goals, and I have found that invaluable in my own life.

Thanks so much to Michael for correcting misinformation and satisfying my curiosity!