Via the Daily Dish, I found an article by Howard P. Kainz, that argues that the media’s relative comfort with Romney’s religion is proof that most Americans don’t consider Mormons to be real Christians. Here’s a pull quote:

[T]he fact that Mitt Romney, the first Mormon candidate for the presidency in our nation’s history, is not only a bishop in the LDS church but a High Priest of the highest echelon (the “order of Melchizedek”) within that religion, and is not being opposed because of the “separation of church and state,” is an indication that Americans do not consider him a bona fide Christian. In contrast, one can imagine what would happen if a Catholic or Lutheran or Episcopalian bishop or priest sought the presidency. An impossibility! … It is becoming clear that—from the ‘ordinary’ Christian point of view—Mormon “high priesthood” is a sui generis order, possibly analogous to higher Masonic degrees, incorporated into a religion quite different from most Christian denominations.

I was a little suspicious of the correspondence Sullivan and Kainz drew between Romney’s priesthood and that of Catholicism (which, as TV Tropes points out, we tend to treat as the default form of Christianity). Luckily, I’ve got a geeky Mormon friend, who’s very generous with his time, and he agreed to do a guest post here to give us all a crash course in what the Mormon priesthood entails.

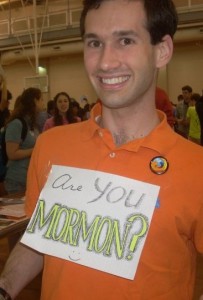

Michael Haycock is a classmate of mine, and has his own blog at Not A Tame Lion. He’ll be going to Claremont Graduate University’s School of Religion in the fall. After this post, there will be two additional posts of Q&A, where Michael answers some of my questions about Mormon hierarchy, theology, and culture. Michael’s post starts below his picture, and he’s put all the LDS-specific terms in bold.

Kainz gets his reasoning all wrong, mainly because Mormon definitions of ecclesiastical terms are drastically different from typical Christian ones, even though we use some of the same words. Honestly, a (relatively) quick primer on Mormon jargon and administration would go a long way to allay many people’s fears.

(Note that when I say “Mormon” or “LDS” I am referring exclusively to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, not any of the many offshoots.)

First, nearly all active (regularly-attending and involved) Mormon men are “priests after the order of Melchizedek.” If a man’s been on a mission, been deemed worthy after turning 18, or held any significant leadership position, he holds the Melchizedek Priesthood and is designated an elder. Older men, holding higher positions, are ordained to be high priests. (There are higher offices – patriarch, seventy, apostle – but they are much rarer.) These titles are called offices in the priesthood, and they determine what leadership positions a man can hold and which ordinances (rituals) he can perform. Once a man has been ordained to one of these offices in the Priesthood, he holds that authority until he dies unless his rights are removed due to disciplinary action.

On the other hand are callings, which are positions of responsibility that Mormons hold. In the LDS vernacular, “calling” doesn’t have the same sense of “vocation” that it does in other contexts: Mormons do not perceive some divine “call” and pursue it; instead, their leaders extend a calling to them as an assignment they can accept (or, if circumstances do not allow acceptance, decline; this is rare, though). Any position in the LDS Church is regarded as a calling, from Primary (children’s Sunday school) teacher to missionary (truly the only calling for which one volunteers oneself) to stake president. Both men and women receive callings, and some callings are generally gender-specific, like that of bishop or stake president (for men, because they are positions within the Priesthood).

All callings, however, are temporary. When you accept a calling, you are officially set apart for that duty; when the responsibility is going to be passed on to another person, you are released from that calling, and your responsibility shifts to your new calling.

Because the LDS Church has a completely lay ministry, only very few Church authorities maintain their positions through their lives: the First Presidency of the Church (the president and his two counselors) and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles (the twelve men who with the Presidency lead the Church). Even the Quorums of the Seventy, just below them hierarchically, only hold their positions until they’re 70-75 years ago, and then they’re designated “emeritus” – a position of respect, but no official authority.

Very few other callings are full-time positions (mission president and missionary are two that are because they involve leaving your home for 3 years or 1.5-2 years, respectively), and even those get no financial remuneration. In the case of missionaries, for example, one gets a minimal stipend from the Church derived from funds to which every missionary has already contributed. Thus, despite the demands of their callings in time, effort, and energy, people in local positions of authority must hold down their jobs, families, and perhaps studies in addition to having sometimes upwards of 40-50 hours of church work a week. (Scoutmasters have the exquisite joy of spending a week of summer vacation time camping with rambunctious teenage boys.)

But I don’t think Kainz even knows the term “stake president” and the difference between that and a Mormon “bishop,” both of which are positions that Romney has held, nor what men in these positions do. The smallest geographic unit of the LDS Church is called a ward, which is presided over by a bishop and his two counselors. A stake consists of at least five wards (and/or branches, which are small wards). Bishops are entrusted with overseeing the smooth operation of the unit they are called to lead. They extend callings, collect tithing funds, help manage local church finances, participate in the distribution of welfare funds, authorize some rituals (like baptism), counsel their fellow congregants, and interview members to ascertain their worthiness to participate in special ordinances and ceremonies in the temples or to receive new callings. Stake presidents do much the same thing, just on the next level of organization up.

Note that there are upwards of 28,000 bishops (or the equivalent) and nearly 3,000 stake presidents in the LDS Church worldwide: Romney, even when in a position of “authority,” was one of thousands, each of whom outside his assigned sphere has no authority and minuscule influence. Unlike in some other churches, these figures do not even vote on general policies of the Church.

Mitt Romney, having been released from all his callings that put him in positions of local leadership, has no residual ecclesiastical authority in the LDS Church. The most he could have is a little bit of symbolic weight as a very publicly prominent figure, but he is admirably reluctant to place himself in a position wherein he would attempt to formally represent the Church. In his mind, this silence is most likely a sign of respect and deference; passing himself off as an expert on doctrinal matters would be overstepping his bounds. (Though I won’t vote for him, I still thank him for not making himself into the “Mormon candidate.”)

Moreover, ANY male adult Mormon politician – including Harry Reid, Senate majority leader, Orrin Hatch, and other LDS congressmen, Cabinet members, or other politicians – holds the Melchizedek Priesthood. And this issue seemed to have been settled over a century ago: in 1904, Mormon apostle Reed Smoot (one of the top fifteen leaders of the LDS Church, a position Mitt Romney has never even approached) was elected to the US Senate and subjected to four years of congressional hearings to determine his eligibility for office. In the end, he was confirmed and allowed to serve. Another LDS apostle, Ezra Taft Benson, served as Secretary of Agriculture under President Eisenhower. It’s now 2012; are we going to backslide now?

In the end, if people complain about Melchizedek Priesthood holders serving in public office, they’re not only turning back the clock but effectively disqualifying all Mormon men from politics. Of course, this would lead to the situation in which only Mormon women, who are not ordained to the priesthood and are not currently represented in the US Congress, would be the only Mormons eligible for (American) office. Some might say that this would be a sort of hilarious poetic justice to repay years of ecclesiastical patriarchy. I know I’d get a good chuckle from it.