The last two song and sentiment posts have touched on problems of uncertainty. How does Floyd derive comfort from his series of questions about heaven? Why does being unblinded leave Nurse Fay Apple more uncertain that she was in ignorance? The last song I want to discuss is from Man of La Mancha. In “What Does He Want of Me” Aldonza’s song follows the same structure as Floyd’s–a litany of questions–but instead of finding comfort, she seems to be as discomfited as Nurse Fay Apple. You can listen to the song below (with slightly different lyrics than the revival version I’m quoting).

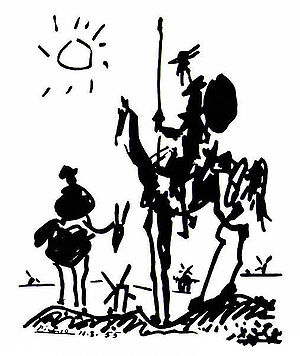

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=spRnVJ8MDoAAs staged in the revival, Aldonza questions Sancho Panza, the squire of the Mad Don Quixote, about his master’s ways. [This is different than in the audio above, where the song is addressed to Quixote. I prefer the revival’s relyricization, because Aldonza cannot appeal to Quixote for explanation, but she might ask Sancho to explain interpret the man he follows]. Quixote is a holy fool, jarringly out of step with the world. In the musical, his inability to find a place in this Spain is not because of some flaw in himself; it is a rebuke to the world that cannot accommodate his abandonment of self.

Why does he do the things he does?

Why does he do these things?

Why does he march

Through that dream that he’s in,

Covered with glory and rusty old tin?

Why does he live in a world that can’t be,

And what does he want of me…

What does he want of me?

It’s not hard to translate Aldonza’s questions to the experience of the followers of Jesus. Think of the man who walks away after Jesus asks him to sell all he has and give it to the poor. Or the disciples who flee after Jesus reveals the hard teaching of the Eucharist. They, too , must have thought:

No one can be what he wants me to be,

Oh, what does he want of me…

What does he want of me?

But why are Quixote’s unspoken demands frightening to Aldonza. If he asked for the plainly impossible (“Aldonza, sprout wings and fly”) or obviously mistook her (confusing her with the very distinct Sancho, not the ideal of Dulcinea), he would be ridiculous, but there would be no threat to Aldonza. Dulcinea is just close enough to possible that a little seed of fear sprouts in Aldonza that she might be called to be what Quixote asks.

Aldonza doesn’t just ask what to do about Quixote, which would leave her in the comfortable, spectator position of his relatives. By asking “What does he want of me?” she acknowledges a relationship between them. And she questions Sancho urgently about what, exactly Quixote wants from her, because sooner or later, she’s going to have to decide whether to deny it to him.

Doesn’t he know

He’ll be laughed at wherever he’ll go?

And why I’m not laughing myself…

I don’t know.Why does he want the things he wants?

Why does he want these things?

Why does he batter at walls that won’t break?

Why does he give when it’s natural to take?

Where does he see all the good he can see,

And what does he want of me?

What does he want of me?

Aldonza is stuck on the horns of Lewis’s Trilemma: Lunatic, Liar, or Lord. If Quixote’s claim can’t be laughed off, then someone must have the authority to ask Aldonza to be more than she is. But since Quixote is just a man, Aldonza can’t answer his demand with Augustine’s prayer, “Give what you command, and command what you will.” Quixote has unblinded her but doesn’t have to power to lead her, so Aldonza despairs in the gulf between ought and is.

But, for a Christian, there’s no begging off being what He wants you to be, since we’re given a more trustworthy guide than Quixote. But the demands he makes have a tendency to sound just as foolish. I’ve said before I tend to like hymns with a martial tone (especially “God Whose Purpose is to Kindle“), but I think the one that’s most likely to make your blood run cold is “The Summons.”

Will you let the blinded see if I but call your name?

Will you set the prisoners free and never be the same?

Will you kiss the leper clean and do such as this unseen,

and admit to what I mean in you and you in me?

The horror of that let!

Christ calls us Dulcinea already, and rebukes us for clinging to ‘Aldonza’ in our fear. We’ve already been offered the power to be what we ought to be, but, moment by moment, we decline to exercise it or acknowledge it. We couldn’t possibly be so beautiful or so strong. Better to stay small on the sidelines than acknowledge every moment we’ve spent shirking til this point. The first ‘Amen’ is an acknowledgement that we hadn’t said it until now.

But better to bite the bullet and admit that I have greatly sinned, in what I have done and in what I have failed to do, than to deny culpability by denying that I can and should be better.

T-1 day.