This month, the Patheos Book Club is reading Catholic Spiritual Practices: A Treasury of Old and New, a collection of description of and reflections on common Catholic spiritual practice. The book is essentially a tasting menu; each of the twenty-six meditations is only a few pages long. It’s the book equivalent of Lewis’s Wood between the Worlds (or Grossman’s Neitherlands).

This book alone would not be enough to get you engaged in any form of spiritual praxis, but you might end up with a Catholic Spiritual Practices-shelf, full of books you got after having your attention caught by one of the brief essays. The editors of the collection did a nice job recruiting priests, religious, and laypeople to introduce these practices. In the space allotted, some authors share their personal experiences with a prayer tradition, and others talk about the way a particular discipline has emerged through and shaped Church history. Not all of the essayists are Catholic, since some of these traditions are widely appreciated across Christendom, so, sometimes the way that a practice fits into a specifically Catholic theology is left as an exercise to the reader.

I was pleasantly surprised at how many of these traditions I’ve encountered (it’s nice to have a vibrant parish with a lot of enthusiastic, talkative people my own age). One that has proved affecting for me is the Ignatian practice of the examen. So, in the spirit of the book I’m reviewing, I’ll give you a short personal reflection in case it sparks your interest.

After I read The Presence of God by Father Anselm Moynihan, O.P., I had a better idea of what prayer was, but not how to do it. You see, at one point, Fr. Moynihan advises:

The twofold practice of often recalling to ourselves the fact of God’s indwelling in our heart and of continually addressing our intimate, secret conversation to him instead of ourselves, is one of the best means of disposing ourselves for the operation of the gift of wisdom and obtaining from him the experience of his presence.

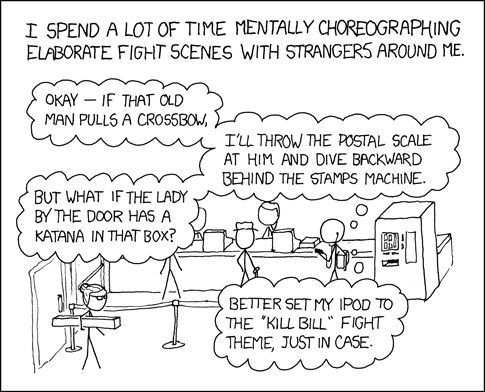

The trouble is, my internal monologue tends to look a lot like this:

So I wasn’t really sure what to do with the advice from the book. However, after my baptism, I read The Examen Prayer: Ignatian Wisdom for Our Lives Today by Father Timothy Gallagher. The Examen is a way of reflecting on the day through prayer. I started doing it after Mass, and it made it a lot easier to prepare for Confession and to spot moments where I needed to ask God’s forgiveness and aid.

Noticing sin and uncharity feels a lot like spotting Ugh Fields in LessWrong parlance. The trick is noticing the thing you’re flinching away from and then turning into it. It’s pretty hard to do, since, when you notice something you’ve screwed up, your first thought is usually “I suck,” which isn’t a nice-feeling thought to think. So, essentially, you punish yourself for noticing, and train yourself to avoid noticing your sins in the first place. (Imagine a company that cared a lot about quality control, but where management freaked out and got angry when employees spotted errors to correct. Soon you’d have trained your workers to not bring them to your attention).

LessWrong tends to recommend rewarding yourself immediately for noticing the error. Give yourself an m&m, pump your fist and say “Go me!” anything to break the conditioning pattern. And the circuit-breaking thought that helps me get through the Examen is gratitude.

Here’s how I think of it: sin is like a cancer; it grows and spreads through my character. Even a small error can quickly become dangerous if unchecked. Now, the trouble when coming up with cancer treatments isn’t sussing out ways to kill cancer cells, it’s finding a way to preferentially kill them while leaving our healthy cells untouched. In a similar way, the real struggle is disentangling myself from my sin. There a basically two approaches to the cancer problem: you can find a drug or a treatment that attacks a weakness peculiar to cancer cells (i.e. disrupting their abnormal angiogenesis) or you can try to make sure your poisons are administered in a localized way right where the cancer is (targeted radiation, nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery).

When I can, I like to do my daily Examen in the church after Mass. When I notice a flinch and lean into it, one thing I reflect on is that I’ve just consumed the Eucharist. Christ’s body is a part of my body, and, by holding my transgressions in my mind, I’m helping that grace be precisely targeted. It’s beyond my ability to create a balm in Gilead, but the Examen helps me cooperate with its administration.