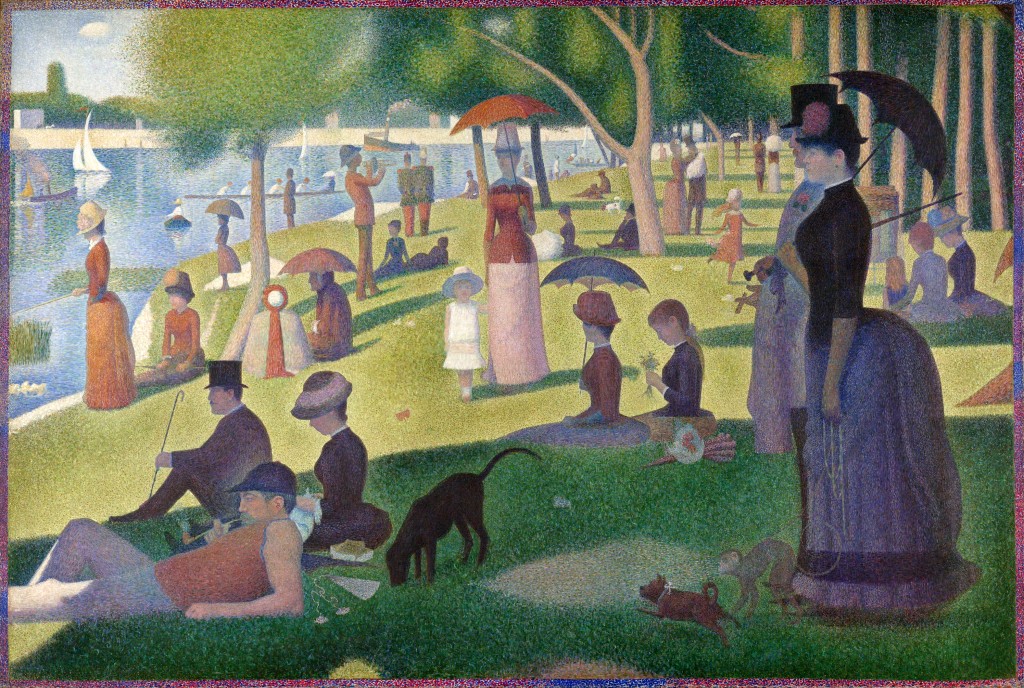

So, apparently if I host an installment of the Stephen Sondheim film festival the night before a silent retreat, I end up spending a lot of time meditating on Seurat instead of Scripture. A few weekends ago, I invited friends over to watch Sunday in the Park with George, Stephen Sondheim’s musical about Georges Seurat’s creation of A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. (It’s on Amazon instant streaming, go enjoy!).

In the first act, Georges struggles to express himself to his lover, to his mother, and to his friend. And his great work can’t quite bridge the gap, since his compatriots conclude that his pointillistic style has “No Life” (“His touch is too deliberate somehow”). When he and his lover, Dot, have their falling out he tries to explain the intimacy he feels they share:

George: I cannot divide my feelings up as neatly as you, and I am not hiding behind my canvas-I am living in it.

Dot: What you care for is yourself.

George: I care for this painting. You will be in this painting.

Dot: I am something you can use.

George: I had thought you understood.

Perhaps it would be easier for Dot to understand if she could see George sketching during the earlier number “The Day Off” (below). As George studies the figures on the island, he’s drawn into their experience. Although he appears absent and distant in dialogue with others, when he draws them he puts on their characters and mimics their cadences in brief musical monologues.

But it’s hard for the audience to decide if looking from behind his sketchpad gives George a genuine intimacy with the people he paints, or if it just simplifies them enough for him to be able to embroider their personalities as suits him. Is he really seeing Dot, his beloved, or just enough of an armature for him to hang his own inventions on?

It’s a question to trouble any lover, including all Christians. When we pray, are we thinking with God or about God? In C.S. Lewis’s Screwtape Letters, a malevolent demon tells his apprentice not to worry when his target turns to prayer, since it’s easy to be misled by the picture we paint:

If you examine the object to which he is attending, you will find that it is a composite object containing many quite ridiculous ingredients. There will be images derived from pictures of the Enemy as He appeared during the discreditable episode known as the Incarnation: there will be vaguer—perhaps quite savage and puerile—images associated with the other two Persons. There will even be some of his own reverence (and of bodily sensations accompanying it) objectified and attributed to the object revered. I have known cases where what the patient called his “God” was actually located—up and to the left at the corner of the bedroom ceiling, or inside his own head, or in a crucifix on the wall. But whatever the nature of the composite object, you must keep him praying to it—to the thing that he has made, not to the Person who has made him. You may even encourage him to attach great importance to the correction and improvement of his composite object, and to keeping it steadily before his imagination during the whole prayer. For if he ever comes to make the distinction, if ever he consciously directs his prayers “Not to what I think thou art but to what thou knowest thyself to be”, our situation is, for the moment, desperate.

As a lover of abstractions, and someone with George-like tendencies to do better with characters I imagine than creatures I encounter, this is a terrifying paragraph to read. I’ll talk a little tomorrow about why neither George nor I should despair (though Dot may well despair of either of us).