In 2014, I’m reading and blogging through Pope Francis/Cardinal Bergoglio’s Open Mind, Faithful Heart: Reflections on Following Jesus. Every Monday, I’ll be writing about the next meditation in the book, so you’re welcome to peruse them all and/or read along.

This chapter is called “The Solitude of Prayer” but, as I read Pope Francis’s meditations on exile — the first, individual one, experienced by Adam and Eve, the Babylonian exile endured by the Jews, the state of Christians described in the Letter to the Hebrews, and, finally, back to the individual in prayer, I felt much more connected to others. Pope Francis describes the experience of separation from God as follows:

In its pilgrimage, our flesh feels nostalgia for the homeland, and it voices its longing deliberately and explicitly in prayer, in the presence of the glorious Lord, the Lord of that homeland we yearn for. Meanwhile, our flesh is caught between feelings and numbness, between grace and sin, between deference and rebellion. It feels the oppression of exile and dreads the long road it must walk; it struggles valiantly to defend its hope. The day that our nostalgia dies, our flesh will cease to pray. Seeking release from exile and from wandering in a strange land, it will make this world its homeland. It will tire of seeking after God.

This was a different take on the experience of being alien/foreign in the world that I’m most used to, the one from C.S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity:

Christianity agrees with Dualism that this universe is at war. But it does not think this is a war between independent powers. It thinks it is a civil war, a rebellion, and that we are living in a part of the universe occupied by the rebel.

Enemy-occupied territory-that is what this world is. Christianity is the story of how the rightful king has landed, you might say landed in disguise, and is calling us all to take part in a great campaign of sabotage. When you go to church you are really listening-in to the secret wireless from our friends: that is why the enemy is so anxious to prevent us from going.

I’ve liked the romance and urgency of Lewis’s framing since the first time I’ve seen it, but even though Lewis’s story is explicitly about conspiracy, I’ve tended to think about it as a solitary endeavor. Partially as carry-over from my Stoic-leanings, I prioritize things withing my locus of control — I think of myself as a lone operative, living in secret, focused on what I can do, alone. I don’t think as much about cultivating and maintaining nostalgia and love for the homeland I’m serving (due to Kantian-leanings, I try to work off of duty alone, unless I deliberately reflect). I think less about what to do in community, particularly when it’s something as comforting (which I tend to reinterpret as ‘indulgent’) as reflecting on the home we’re seeking and rejoicing in each other’s love for it.

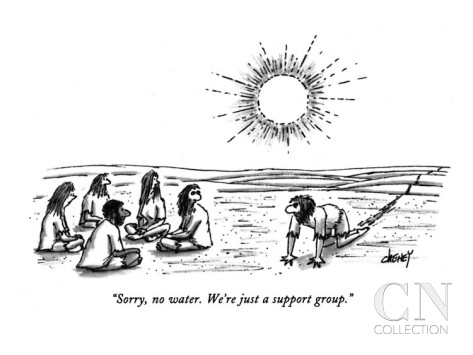

But Francis’s consideration of exile as a pilgrimage focused my thoughts on the other pilgrims. It’s exhausting to live in exile, and I think I’d do a lot better to think about more of my interactions with others through this framework. When I run into people who are sad or brusque or even cruel, I should do more to remember that I’m interacting with someone who is tired and who encounters far less fellowship than ze thirsts for. I’m meeting someone who has to speak everything in a foreign, clumsy language, which is often frustratingly misunderstood.

But I don’t mean by all of this simply that I should be a bit more patient with people (though it’s not a bad idea!). The person I’m talking to is strained by living in exile, but I don’t have to be content simply accomodating the difficulty; I can ameliorate it. A premise of Christianity is that we are all exiles together, alien to this world, but not to each other (though we may certainly be alienated). I should be welcoming people in a way that makes it feel like they’ve found some connection to home, not just a bit of hospitality from a stranger.

It seems like I should be trying to pull off the same kind of trick that a currently dead blog described in the context of recognizing and collaborating with fellow exiles:

Imagine two Soviet spies in the Cold War US who have to get in contact with one another. The KGB forgot to give them a silly code phrase like “the wombat feeds at midnight” so they’ve got to figure it out on their own. The Americans know these two spies are trying to get in contact, so if one were to just ask random people “Are you a Soviet spy?” the Americans could quickly guess that the asker was a spy and arrest him.

You are one of the two spies, and you spot someone who you’re about 50% sure is your colleague. How do you confirm they are also a spy with the lowest possible risk of getting arrested?

I bet there’s some fancy cryptographic solution here, but my intuitive strategy would be as follows:

Me: Excuse me, sir, do you know any good borscht restaurants around here?

Other Spy: Ah, borscht. I love borscht!

Me: I hear Russian borscht is the best. Have you ever had any?

Other Spy: Yes, I was in Moscow once many years ago, before the war.

Me: Really? Have you ever been to [street the KGB headquarters is on?]

Other Spy: All the time! That’s my favorite street! I used to talk to [name of KGB head] a lot.

Me: I am a Soviet spy. Are you one too?

Other Spy: Yes.You would be immediately under suspicion if you asked patriotic Americans “Are you a Soviet spy?”, since they would then know you were probably the other spy yourself. So instead you lead up with a question that seems innocuous to an American who’s not thinking about spying, but to a Soviet who is specifically looking for another spy is sorta kinda suggestive of Russia. The other spy can’t just say “Ah, I understand your code, I too am a spy” because then he might blow his cover to an American who was just looking for some good borscht. So he says something that slightly escalates the Russianness. You can’t just blow your cover now, because you’re still not sure he’s not just an American who appreciates a good plate of borscht himself, so you escalate the Russianness slightly further. In other words, you start off with a conversation that could happen by coincidence, decrease the chance of coincidence a little bit at each exchange only once you get the signal from the other, and eventually the conversation becomes one that couldn’t possibly happen by coincidence and you know he’s the other spy.

The question is how to welcome people. What are the little marks of fellowship I should cultivate to allow others to feel comfortable reaching out to me, to test if they’ve found someone from home? Kindness, sure, and patience. But the attitude that this framing makes me consider is one of “recognition/relief.” What can I do to welcome other people with a sense of “Finally! I’ve been waiting” and have it be true?