In the middle of a column on married couples ineptly supporting single friends, Sara Eckel had a weird model of what happy and healthy relationships look like:

Couples are weird. Relationships — happy ones, anyway — put you a strange bubble, a closed loop of positive reinforcement.

“I love you!”

“I love you, too!”

“You’re the best!”

“No, you’re the best.”

And so forth. It’s like Fox News, except in this case, the propaganda re-circulates between your party of two.

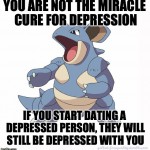

The mutual adoration can make for great relationship harmony; the problem comes when you leave the house. Head swollen, it can be easy to forget that you are not the most wonderful person in the world. Your spouse may think you’re hot stuff, but that doesn’t mean everyone else concurs.

I mean, in a way it echoes one of the distinctions that C.S. Lewis draws between friends and lovers in The Four Loves

Lovers are always talking to one another about their love; Friends hardly ever about their Friendship. Lovers are normally face to face, absorbed in each other; Friends, side by side, absorbed in some common interest.

But the thing that really rubbed me the wrong way in the Eckel piece was the assumption that it’s not just mutual fascination that makes lovers, but both being convinced that the other is perfect. The guys I’ve dated certainly wouldn’t be able to tell anyone that I’m the best, and I wouldn’t want them to think that. I want them to be on my side when I fight to be better.

My Shakespeare professor, Harold Bloom, said that Beatrice and Benedick had the best romantic relationship in Shakespeare, because they were “united in a conspiracy against the world” which he thought was a pretty firm foundation. I like that image, though I’d change “against” to “for.”

People in a good relationship are unquestionably on each other’s side, but the best way to be loyal is to be honest in one’s gaze. It doesn’t help a partner to persist in an error (factual or moral), when the two of you might be able to team up and work on it together.

In Arriving At Amen, I wrote about how this kind of loyalty helped me make sense of petitionary prayer. In the middle of a fight with someone in my debate group, I got the chance to see my antagonist differently.

Instead of imagining Madison and her anger as inseparable, I supposed that there might be some kind of authentic ur-Madison, just as literary scholars discuss the existence of an ur-Hamlet, the original source for Shakespeare’s text. I could imagine a Madison who was happiest and freest and most herself. I could have sympathy for that ur-Madison and imagine that she might feel slightly frightened or trapped by the strength of her anger. My boyfriend probably felt the same kind of sympathy for the ur-Leah he envisioned, hampered and blinded by layers of briskness and callousness.

If that kind of inner self was what God saw and loved—the part of ourselves that was oppressed by sin, not melded into it—it made more sense to me that there was a kind of petition that wasn’t just the equivalent of radioing in spiritual airstrikes to support you in a fight. Rather than calling on God to take my side and make things easier on me or to actively side against Madison and punish her, I could ask God to help me fight for Madison, and to help her fight for me, too.

I was able to shift my attitude a little, but there was still too much distance between me and Madison for me to credibly offer aid (or be too sure I had a specific sense of who ur-Madison was, as opposed to who she wasn’t).

Looking with love honestly is something we can try to do in any relationship, but it’s only within a relationship of trust and intimacy that it makes sense to speak about what we find, see if a partner agrees, and if they want to take up arms together.