Yesterday I ran a post on science fiction and philosophy and the next one coming up is going to be on the distinction between science fiction and fantasy. So let’s make this a science-themed edition of quick-takes (as if I needed an excuse).

But before we move off sci-fi entirely, I want to link to a post on this topic by John C. Wright, an atheist-to-Catholic convert and Nebula nominee for his scifi writing. When it first ran, the essay was titled “Aliens Need Christ’s Redemption, Too.”

From the ever-excellent blog Schneider on Security, a link to the following academic paper: “Science Fiction Prototyping and Security Education: Cultivating Contextual and Societal Thinking in Computer Security Education and Beyond.” The researchers recommend using science fiction as a way to raise awareness of computer security issues and keeping them urgent and relevant. It’s certainly a step up from the password security theatre embraced by plenty of companies and websites.

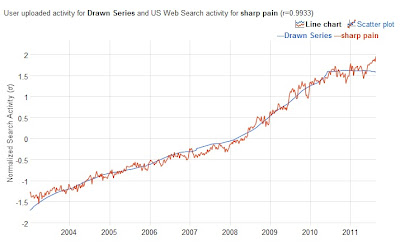

I really enjoy Google’s tendency to release why-the-heck-not? projects, and Draw from Google Correlate is the latest to delight me. You try to freehand draw a trend line with your cursor, and Google supplies a search term that roughly matches that plot.

Apparently we’re a lot more worried about “sharp pain” than we were in 2004. Have fun futzing around.

And, if you’re interested in trying to extract meaning from arbitrary-seeming jumbles of data, maybe you’ll like the research I found via Ezra Klein: an interesting hypothesis about the density of concepts in different languages.

The more data-dense the average syllable is, the fewer of those syllables had to be spoken per second — and the slower the speech thus was. English, with a high information density of .91, is spoken at an average rate of 6.19 syllables per second. Mandarin, which topped the density list at .94, was the spoken slowpoke at 5.18 syllables per second. Spanish, with a low-density .63, rips along at a syllable-per-second velocity of 7.82. The true speed demon of the group, however, was Japanese, which edges past Spanish at 7.84, thanks to its low density of .49. Despite those differences, at the end of, say, a minute of speech, all of the languages would have conveyed more or less identical amounts of information.

A friend of mine calls shennanigans, on the grounds that foreign languages always sound fast, since the unfamiliar phonemes mean you can’t tell when anything begins or ends. I imagine that could be true, but linguists could still observe some languages to be more densely packed than others. I don’t know much about linguistics, though, so I’d appreciate a clarification.

If you’re not already familiar with the Stanford Prison Experiment, check out the wikipedia page and then head over, with everyone else, to Stanford Alumni Magazine, where they’ve published interviews with several of the participants.

The experiment, which took place 1971, randomly divided up a group of volunteers to serve as either guards or convicts in a simulated prison. The experiment swiftly spiraled out of control, as the ‘guards’ began abusing the ‘prisoners’ under their care. It’s become a cautionary example of the corrupting and warping influence of power over people in a dehumanizing situation.

I’ve been catching up with Common Sense Atheism’s read-all-of-Yudkowsky project and one post I read this week (“Unbounded Scales, Huge Jury Awards, & Futurism“) touches on an interesting aspect of social science and cognitive bias. Here’s a preview:

Kahneman et. al., 1998 and 1999, presented 867 jury-eligible subjects with descriptions of legal cases (e.g., a child whose clothes caught on fire) and asked them to either

- Rate the outrageousness of the defendant’s actions, on a bounded scale

- Rate the degree to which the defendant should be punished, on a bounded scale, or

- Assign a dollar value to punitive damages

And, lo and behold, while subjects correlated very well with each other in their outrage ratings and their punishment ratings, their punitive damages were all over the map. Yet subjects’ rank-ordering of the punitive damages – their ordering from lowest award to highest award – correlated well across subjects….

Which is to say: if you knew the scenario presented – the aforementioned child whose clothes caught on fire – you could take a good guess at the punishment rating, and a good guess at the rank-ordering of the dollar award relative to other cases, but the dollar award itself would be completely unpredictable… Taking the median of twelve randomly selected responses didn’t help much either.

So a jury award for punitive damages isn’t so much an economic valuation as an attitude expression – a psychophysical measure of outrage, expressed on an unbounded scale with no standard modulus.

Read the whole thing, and then see what you could do to compensate for this effect.

And, to close closer to where we began, check out two English glosses on a Jesuit’s take on the Christian perspective on computer hacking and open source software. (As you may remember from my posts during senior essay season, I’m very invested in these topics). Here’s a quote to think on:

Mr Spadaro says he became interested in the subject when he noticed that hackers and students of hacker culture used “the language of theological value” when writing about creativity and coding, so he decided to examine the idea more deeply. The hacker ethic forged on America’s west coast in the 1970s and 1980s was playful, open to sharing, and ready to challenge models of proprietary control, competition and even private property. Hackers were the origin of the “open source” movement which creates and distributes software that is free in two senses: it costs nothing and its underlying code can be modified by anyone to fit their needs. “In a world devoted to the logic of profit,” wrote Mr Spadaro, hackers and Christians have “much to give each other” as they promote a more positive vision of work, sharing and creativity.

He is not the only person to see an affinity between the open-source hacker ethos and Christianity. Catholic open-source advocates have founded a group called Elèutheros to encourage the church to endorse such software. Its manifesto refers to “strong ideal affinities between Christianity, the philosophy of free software, and the adoption of open formats and protocols”. Marco Fioretti, co-founder of the group, says open-source software teaches the “practical dimension of community and service to others that is already in the church message”. There are also legal motivations. Commercial software such as Microsoft Word is widely pirated in many parts of the world, by Catholics as well as others. Mr Fioretti advocates the use of open-source software instead, because he doesn’t want people “to violate a law without any real reason, just to open a church document.”

[Seven Quick Takes is a blog carnival run by Jen of Conversion Diary]