I’m working on a post on the atonement and the gospel (for the “Leaving Evangelicalism” series), which I will post sometime early next week. In the meantime, I thought I’d post a section from the prelude of a provocative and important book which critiques traditional, Western Christian atonement theory: Proverbs of Ashes, by Rita Nakashima Brock and Rebecca Parker.

from the preface:

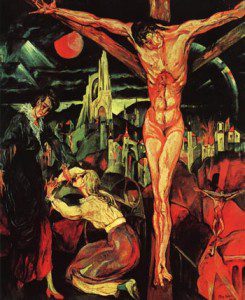

At the center of western Christianity is the story of the cross, which claims God the Father required the death of his Son to save the world. We believe this theological claim sanctions violence. We seek a different theological vision.

What words tell the truth? What balms heal? What proverbs kindle the fires of passion and joy? What spirituality stirs the hunger for justice? We seek answers to these questions–not only for ourselves but for our communities and our society…In the Bible, prophets and teachers repeatedly contend with their religion’s failures and false claims. Job railed against the pious teachings of his day as he struggled with devastating loss and illness. The teachings of his friends reinforced his suffering. “Your maxims are proverbs of ashes!” he protested…

from chapter one:

Over the years, Rita and I [Rebecca] would contemplate the meaning of Jesus’ death. To say that Jesus’ executioners did what was historically necessary for salvation is to say that state terrorism is a good thing, that torture and murder are the will of God. It is to say that those who loved and missed Jesus, those who did not want him to die, were wrong, that enemies who cared nothing for him were right. We believe there is no ethical way to hold that the Romans did the right thing. We will not say we are grateful or glad that someone was tortured and murdered on our behalf. The dominant traditions of Western Christianity have turned away from the sufferings of Jesus and his community, abandoning the man on the cross.

and then the kicker:

Atonement theology takes an act of state violence and redefines it as intimate violence, a private spiritual transaction between God the Father and God the Son. Atonement theology then says this intimate violence saves life. This redefinition replaces state violence with intimate violence and makes intimate violence holy and salvific. Intimate violence ends sin. Behind the holy mask of intimate violence, state violence disappears.

My brief reflection:

I don’t purchase wholesale the critique that Brock and Parker (and many other feminists) levy against

“traditional atonement theology.” There are certainly problems with elements of traditional atonement theology, and common versions of the “penal substitutionary” model of the atonement do lend themselves to ignoring

“state violence” and replacing it with “intimate violence,” a sanctioned and purportedly harmless form of violence. This amounts to an eclipse of human responsibility in Jesus death; it is chalked up to divine initiative and to “God’s plan.” In fact, this atonement theology is often, sadly enough, used to sanction–even if only implicitly–relational violence within families because it can normalize and spiritualize the suffering of victims and it can normalize and even seek to legitimate abuse by the “Father” in the relationship. If Jesus’s suffering was God’s plan and had a redemptive purpose, why shouldn’t your suffering be God’s plan and have a redemptive purpose? Brock and Parker powerfully show the horrible way this logic works in their memoir-theology. And it is important to say that this penal substitutionary model of the atonement is basically what many Evangelicals understand “the Gospel” to be. If that’s what the Gospel is, and if that’s all it is, that’s not good news at all. Not for the weak and vulnerable, anyway.

But I think one can affirm that the story of the cross holds the human actors (Romans, Jewish leaders) responsible for their acts of violence and even that God intended the cross (and resurrection) to accomplish something–salvation. The death and resurrection of Christ was an act of cosmic reconciliation whereby sin was atoned for, salvation effected, death overcome, and and the mechanisms of evil were delivered a fatal–if only eschatologically final–blow. And it was not just Jesus who suffered on the cross. God suffered too. A theologically, pastorally, and politically adequate articulation of the atonement of Jesus does not legitimate continued violence, whether violent acts of aggression by the state or violent acts of aggression within the family or society. It insists that the forces of violence and evil–and their theological justifications–have been crucified at the cross of Christ (thanks be to God) and that it is up to us now to be reconciled–to God and to each other.