Did Jesus believe in the inerrancy of Scripture?

Rob Bowman recently responded to my post, Seven Problems with Inerrancy, with his essay, Seven Problems with  Christian Opposition to Inerrancy.

Christian Opposition to Inerrancy.

In this post, I’m going to address only the first of Bowman’s critiques. Perhaps I can address the others in a new series of posts. He raises some good questions, deserving of serious response.

Bowman expresses disappointment that, like so many other critics of inerrancy, I neglected to deal with Jesus’ own words about Scripture. He says that, “if we are serious about following Jesus Christ, we must accept his view of Scripture.”

Let’s set aside an initial observation, which is the circularity implied in Bowman’s demand. If you assume the inerrancy of the Bible, you can then confidently go to the Bible to see whether what Jesus is (inerrantly) reported as having said about it supports the doctrine of inerrancy.

I’m willing to set the circularity issue aside because (1) most grand claims to authority have at least some circularity to them; and (2) Despite my critique of inerrancy, I tend to trust the Bible’s presentation of things more than I tend to distrust it–particularly when it comes to the gospels; and (3) Bowman has a point: What Jesus said and did, as best we can know it, is of utmost importance to theological belief and Christian practice.

So, then, what was Jesus’ view of Scripture?

In his post, he offers only one example, from Jesus’ teachings in the Sermon on the Mount:

Do not think that I came to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I did not come to abolish but to fulfill. For truly I say to you, until heaven and earth pass away, not the smallest letter or stroke shall pass from the Law until all is accomplished” (Matt. 5:17-18).

Reflecting briefly on the passage, Bowman claims,

That is a clear articulation of the traditional ancient Jewish view of Scripture as verbally inspired by God. The rest of the Gospels consistently attest that Jesus held this view.

This is a very strong claim which hardly seems supported by this one passage. It does suggest, as Bowman points out, that Jesus had a “high view of Scripture,” consistent with the dominant Rabbinic understanding of the Hebrew Scriptures.

But what Matthew seems to want the reader to understand here is that Jesus was indeed the Jewish Messiah and that his Messianic reign would be consistent with–not in contradiction to–Jewish religious life and its authoritative texts. Matthew was written primarily with Jewish Christians in mind and he was obviously concerned to show that Jesus did not desecrate the traditional authorities of Israel and bring in some brand, new thing that was inconsistent with Hebraic self-understanding and religious practice. Rather, Jesus showed his disciples the importance of following Torah, but keeping the main thing the main thing.

It’s worth noting, though, that immediately following this passage (5:21-48), Jesus makes a few adjustments to the Torah. These are the “you have heard it said…but I say unto you” texts. And they are not insignificant adjustments. Jesus intensifies the Torah teachings on lust/adultery, marriage/divorce, retaliation/generosity and loving the enemy.

This last intensification is important (against retaliation and against violence), because Jesus presses upon his follower the primacy of love and forgiveness over violence. How should one understand so much of the Old Testament, so much of which seems to provide divine approval of violence against enemies? Jesus’ teachings appear as a dramatic update or even disapproval of the “divine genocide” or “holy war” texts in the Old Testament.

While Jesus still shows respect for the authority of the Law, there is at least a sense in which he updates the commandments to allow for the new reality which has come into being–the new reality effected by the arrival of the Kingdom of God, which Jesus himself embodied.

But I still agree at a basic level that this text–as does the Sermon on the Mount on the whole–presents Jesus as highly esteeming the Torah and affirming its central role in the life of the discipleship community.

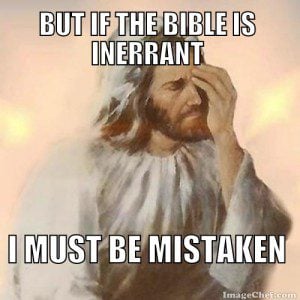

But is this evidence of Jesus’ “belief in inerrancy”? I don’t think so.

First, I have to give a basic definition of inerrancy. There are many varieties of inerrancy, but a typical definition is that the Bible is without error in everything about which it speaks. Inerrancy is usually distinguished from infallibility in that former (stronger) version means that the Bible’s truthfulness extends not just to matters of theological, ethical/moral, and soteric (salvation) significance, but to history and science, too. I take it that Bowman would agree with this basic definition, if it would allow for minor discrepancies: slight textual variants, “rounding up” of numbers, etc., such as those “minor” issues which are acknowledged in the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy.

But now, back to the Bible.

While he only gives the one example (Matt. 5) in his post, he also provides a link to a rather lengthy essay he has written arguing for Jesus’s affirmation of inerrancy. But here’s a friendly warning: one has to read rather far down to get to his discussion of NT texts.

In that material (if I can adequately condense it here), Bowman refers to Jesus’ use of the formula, “It is written,” to “introduce quotations from Scripture.” He also refers to the “Have you not read” phrase to highlight Jesus acceptance of Scripture’s authority. He refers to the Matt 5:17-18 “I did not come to abolish but to fulfill” passage (which I discussed above). Bowman also notes that Jesus cited Scripture passages to defend his actions to the Pharisees and other religious opponents (i.e. breaking the Sabbath rules with his disciples).

In my view, these examples do not support the notion that Jesus believed in inerrancy. Rather, they support the notion that Jesus accepted the (Old Testament’s) authority and that he spoke in terms of its assumed authority, both with his disciples and his opponents, to make the points he wanted to make–but those points had to do with religious and ethical matters, not with matters of history and science–as in the definition of inerrancy provided above.

I think Jesus had a basically functional and instrumental view of Scripture’s authority. He assumed the Bible to be inspired of God and therefore bearing a distinct stamp of authority, but it was for a purpose which exceeded the question of its being grounded in or by complete truthfulness with respect to history, cosmology, biology, and so on.

In one of Bowman’s stronger examples, he points out that Jesus “assumed the key events in the account of Jonah were factual.”In Matthew 12:40, Jesus is reported as saying, “For as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of a huge fish, so the Son of Man will be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth.”

Bowman suggests that “This is worth noting, since Jonah is one of the most ridiculed books of the Bible today.” Now, it may be that Jesus believed in the historicity of a man named Jonah who was swallowed by a large fish. But it also could be the case that Jesus was simply alluding to it as a common cultural background story to make the more important point: “behold, something greater than Jonah is here!” The real point was not about a historical Jonah (and certainly not “the inerrancy of the Bible”), but the primacy of Jesus himself, who will shadow the old Jonah story by the glory of his death and resurrection. The “three days” in the belly of a fish was a powerful literary/poetic connection to make to foreshadow his coming death.

Bowman then lists a number of other examples, each of which has to do with a moral or soteric teaching. With each example, Bowman is insisting that Jesus affirmed the authority of the Old Testament and appealed to its authority to make points about morality, justice, or salvation. I don’t dispute any of that. Those statements do not prove that Jesus held a (conservative evangelical) view of inerrancy. They do show that Jesus assumed, affirmed, and taught on the basis of Scripture as authoritative.

Bowman’s stronger example is Jesus’ reference to the “fulfillment of Scripture” in the unfolding events of his life. The gospels present Jesus as having an understanding that his own life was connected to prophecies of the Hebrew testament. There is a “historical” element here, in that Jesus’ perceived the events of his own life as linked to Hebraic prophetic predictions of the Messiah.

But to claim from this that Jesus viewed all of Scripture as being inerrant in all historical/scientific matters is just claiming far more than the evidence bears out. We could just as easily infer by this collection of texts that Jesus understood himself to be the ultimate referent point of the Old Testament and that, when the Scriptures pointed to his coming (incarnation) they reflected a sense of a true entrance of the son of God into historical time.

But I don’t think we can conclude from this that Jesus would insist on inerrancy; that, for example, Elisha’s axe-head actually floated or even that Jonah was an actual historical person who lived in such-and-such a time and place. In other words, there is no final way to claim that Jesus’s viewed every text, story, or teaching of Scripture with the flatness (or equality) as many evangelical proponents of inerrancy do. On first glance, I would suggest that the texts that Bowman presents us show a Jesus who assumes, affirms, and employs Scripture’s authority, but more along the lines of infallibility rather than inerrancy. And he does so to make points that have really nothing to do with the “nature” of the Scriptures themselves.

One text that Bowman omits to discuss is worth bringing up at this point:

I have testimony weightier than that of John. For the works that the Father has given me to finish—the very works that I am doing—testify that the Father has sent me.And the Father who sent me has himself testified concerning me. You have never heard his voice nor seen his form, nor does his word dwell in you, for you do not believe the one he sent.You study the Scriptures diligently because you think that in them you have eternal life. These are the very Scriptures that testify about me, yet you refuse to come to me to have life. (John 5:36-40)

Jesus is here speaking to Jews who uphold the “traditional view” to which Bowman often refers. Yet Jesus rebukes their undue emphasis on the written words of the Scriptures as being sufficientlylife-giving of themselves. These words testify to Jesus–and that’s important. But Jesus warns them not to substitute the words which testify for the reality (or person, rather) to which they point. It’s the Word, not the words, that ultimately matter.

I’m not suggesting Bowman himself is guilty of replacing Jesus with the Bible as the object of his devotion. But I do think that this text offers something of a “counter-evidence” to his claim that Jesus affirmed the inerrancy of Scripture. Now, there is a way to affirm inerrancy that does not capitulate to the modernist and fundamentalist temptation to replace the primacy of relationship to Jesus with confidence in the Bible itself.

Bloesch, in Holy Scripture, suggests a potential “biblical” view of inerrancy:

In biblical religion error means swerving from the truth, wondering from the right path, rather than defective information (cf Prov 12:28; Job 4:18; Ezek 45:20; Rom 1:27; 2 Pet 2:18 Jas 5:20; 1 Jn 4:6; 2 Tim 2:16-19). Scriptural inerrancy can be affirmed if it means the conformity of what is written to the dictates of the Spirit regarding the will and purposes of God. But it cannot be held if it is taken to mean the conformity of everything that is written in Scripture to the facts of world history and science (107).

This sounds pretty good to me. The inerrancy I reject is one which holds the Bible to be true, or error-free, in everything that it might possibly touch upon; what it is assumed to be about is not just theological, moral, or soteric (what is necessary for salvation) teachings. Certainly there is more in the Bible than theology, moral, or soteric teachings; it includes plenty of other material, including (apparently) historical matters, legal and organizational guidelines, poetry, proverbs of wisdom, and so on. But if we’re going to be honest about so much that the Bible contains, we need to be willing to say that it is not flawless, or perfect, or without problems, or not calling out for a bit of updating. Going beyond Bloesch, I would say these problems include not just matters of historical details or scientific worldview, but matters of morality as well.

The traditional inerrantist is not ready to admit to genuine errors in these other matters (e.g. matters of history and science–or certainly in morality), because then it puts the interpreter on the slippery slope toward epistemic chaos: how can we decide what in the Bible to trust and what not to trust? This is a difficult question, to be sure. But I’d rather live with the difficulty of that question than with the over-reaching ideology of the traditional, evangelical “doctrine of inerrancy.”

I affirm, with Bowman, that the gospels present us with a Jesus who related positively to the Torah–as well as to the Prophetic writings–and held them in high esteem as religiously and even ethically authoritative (though he also felt quite free to update them where needed). The Old Testament was the moral and theological foundation for Jesus’ self-understanding and teachings about the kingdom.

But I think we’d all be better off if we would learn to focus our readings of Scripture today through the lens of the centrality of Jesus, rather than via unjustifiable presumptions about the “inerrancy of the Bible.”