The gospels include lots of stories of Jesus healing people. Some examples: unknown diseases, leprosy, blindness, deafness, incessant bleeding (“flux/issue of blood”), paralysis, epilepsy, demon-possession, and yes–death.

Here’s a survey of Jesus’ healing miracles in the gospel of Matthew, including both summative statements and individual accounts:

Summative: Jesus healed diseases, alleviated pain, cured epilepsy, exorcised demons, cured paralysis (4:23-24)

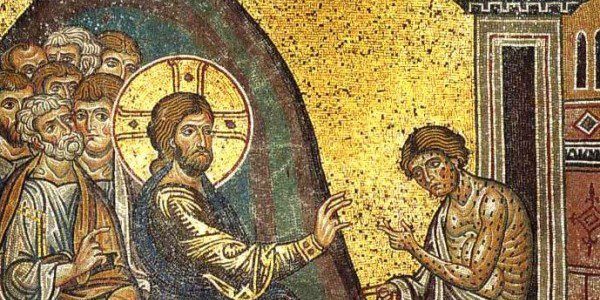

Man with leprosy (8:1-4)

Centurion’s paralyzed servant (8:5-13)

Peter’s mother-in-law (sick with fever): (8:14-15)

Summative: “many who were demon-possessed…drove out the spirits with a word and healed all the sick” (8:16)

Two demon-possessed men (8:28-34)

Paralyzed man (9:1-8)

Synagogue leader’s daughter (dead, Jesus raised her to life) (8:18-19, 23-26)

Woman suffering from continual bleeding (9:20-22)

Two blind men (9:27-31)

A demon-possessed and deaf man (9:32-34)

Summative: “healing every disease and sickness” (9:35)

“Jesus called his twelve disciples to him and gave them authority to drive out impure spirits and to heal every disease and sickness.” (10:1)

“man with a shriveled hand” (12:9-14)

A man who was demon-possessed and blind and mute (12:22-37)

Summative: (In his hometown): “And he did not do many miracles there because of their lack of faith.” (13:58)

Canaanite woman’s demon-possessed daughter (15:22-28)

Demon-possessed boy (seizures) (17:14-20) // disciples couldn’t heal him, because they had little faith (Jesus said)

Two blind men (20:29-34)

Summative: Healed many of the blind and lame at the temple. (21:12-15)

Now, a few thoughts on these healing stories:

Healing was an important part of Jesus’ vocation and Messianic identity.

Obviously, Jesus’s healing miracles were central to his ministry as portrayed in the gospel (certainly in the gospel of Matthew). They were testimonies to his legitimacy as the true Messiah and the Suffering Servant.

Healing was more than transforming individuals; it was about transforming structures of society.

Healing is not just about transforming individual situations, but it’s also–and maybe even more so–about challenging and changing unjust, oppressive, or perverted structures. A few examples: Jesus’ healing miracles displayed a willingness to transcend or set aside purity laws and in-group / out-group mentalities perpetuated on the basis of those laws by the religious leadership. He touches sick and unclean women (including a woman with the “issue of blood,” a woman with a fever, and a Gentile). He also touched lepers and corpses.

He healed on the Sabbath, much to the dismay and ire of the Pharisees, for whom the oral Law (supplement to the written Torah) prohibited doing good works for other people on the Sabbath–even though (as Jesus points out) they made provisions for getting their animals out of the ditch and protecting their own livelihoods.

Jesus’ healing miracles show that his mission is to disrupt and disempower the “Domination Systems” (Walter Wink), or systems (political, economic, religious, etc.) that perpetuate injustices and inhumanity toward certain non-privilege classes or individuals. Jesus showed a willingness to challenge the powers of the Domination Systems by crossing the boundaries established by those systems and pointing out places where they perpetuated injustices. .

Healing miracles were a testimony to the arrival of the Kingdom of God.

Jesus not only challenged unjust systems and structures, he also showed power over evil and death, and the destructiveness and oppressions that are consequences of those powers. Sickness and death and demonic oppression are all now under the power of Jesus and the Kingdom he announced and embodied. This doesn’t mean that those consequences are now no longer in effect (obviously we still deal with them daily and death is inevitable for us all). It does mean that we do not need to see them as having the last word, so long as we believe that the Kingdom will ultimately and finally arrive in full.

Healing miracles require human participation–that is, faith.

The healing stories, certainly the individual stories that are highlighted in the gospel, all involved some kind of assent, willingness, or–most centrally–faith in God and in God’s power.

It’s not always clear what comprises faith in each case, and there seem to be differences among them, but it seems easy to conclude that, in general, faith involves some kind of belief that God can bring about healing and that Jesus represented the authority of God and the presence of God’s reign.

The disciples were not able to cast out an evil spirit because they lacked faith. This suggests that healings were not so much dependent on some magical formula as they were about acknowledging God’s ultimate authority over creation. There was something unique about the period of Jesus’ life and the apostles in which healing miracles were done with consistency and remarkable power–to show that the Domination Systems are overcome by the kingdom of God.

What do we make of the commonality of demon-possession and exorcism in the gospels?

The gospels, especially Matthew and Mark, are filled with stories of demon possession and exorcism. Jesus is pictured, in the words of NT scholar James Dunn, as a very “successful exorcist.”

But what are we to make of these exorcisms today, in a context where we certainly don’t default to demon-possession as an explanation of epilepsy, or blindness, or deafness, and so on? Obviously there were dramatic stories of demon-possession too, which depicted the demon(s) basically taking over the whole person and even speaking through that person somehow to Jesus. We don’t see a lot of that around town these days. Although, I’ve heard stories from people from non-western and /or remote contexts where some kind of demon-possession–or supernatural evil–is assumed to happen with some regularity. Should we chalk this up to differing interpretations of the same event–i.e. using mythological categories to explain events that could be explained otherwise? I’m not prepared to conclude either way.

In any case, if we focus on the comparative lack of demon possessions and excorcisms between the typical modern context and that which is depicted in the gospels, the contrast can appear jarring. Ruldolf Bultmann succinctly describes this contrast–and the implications–in an oft-quoted observation:

It is impossible to use electric light and the wireless and to avail ourselves of modern medical and surgical discoveries, and at the same time to believe in the New Testament world of spirits and miracles.

We’re in a different setting, to be sure. We have access to a multitude of different and more adequate explanations for a host of sicknesses, diseases, and psychological disorders than did the people of the first-century (including, obviously, the gospel writers).

So what’s going on? One helpful point is that, as one article notes, neither the gospel writers nor Jesus “thought of demons as individual spirits of the dead acting on their own capricious influence.” Rather, “evil and hostility to God was perceived as much more unified and deliberate and demons (whether thought of as a single demon or as many demons) were only one way of understanding or picturing the malicious effects of that single will opposed to God” (p. 217).

Certainly in the NT context, evil was understood to be real and powerful–and those powers of evil set themselves directly against the in-breaking reign of God.

However we understand demon-possession and exorcism in the gospels and in our experience today, we can affirm that powers of evil do set themselves against God and God’s kingdom. And we can find ourselves participating in or instrumental for those powers, too–even if unwittingly or unintentionally.

Jesus went throughout Galilee, teaching in their synagogues, proclaiming the good news of the kingdom, and healing every disease and sickness among the people. 24 News about him spread all over Syria, and people brought to him all who were ill with various diseases, those suffering severe pain, the demon-possessed, those having seizures, and the paralyzed; and he healed them.

The hardest question of all might be: Why doesn’t God appear to do more healing miracles today?

If we take the NT gospels at least somewhat straight-fowardly and historically, and if we assume that Jesus did perform at least some–if not many (or all)–of the miracles that the gospels attest of him, why shouldn’t we expect that sicknesses and disease today can be healed by the power of God–if only those who are sick (or those who are praying for them) have enough faith?

This is a hard question and it can be existentially and spiritually difficult to work through, especially for those dealing with significant disease and loss themselves. Obviously, death awaits us all at some point, but some situations, some sicknesses, some experiences of death, suffering, and loss are easier to accept than others. And very often, it seems, prayers just aren’t answered. And surely most of us don’t want to conclude the reason those prayers aren’t answered is because people just don’t have enough faith, haven’t prayed “hard enough,” or because God’s love and grace doesn’t extend to everyone.

So what do you think? How would you answer this for yourself?