I know that after my departure savage wolves will come among you, and they will not spare the flock. And from your own group, men will come forward perverting the truth to draw the disciples away after them. (Acts 20:29-30)

How do we know who to believe when we don’t have access to hard evidence?

The first time I was asked to weigh in on this question, it was about allegations of sexual abuse within the context of a religious community. When the alleged abuser denies the abuse, how do we know who to believe?

But the question is bigger than that. How do we ever know who to believe when we’re presented with conflicting statements and no physical evidence?

When we are forced to evaluate from the outside, we can’t ever be certain, but through a process of discernment we may be able to get to the point of being reasonably confident.

It’s the process of discernment we tend to skip over. We don’t want to live with uncertainty, especially when the truth revolves around something as important as abuse.

Some cases are easier to discern than others, but the process is the same, even if one walks through this process unconsciously.

What might that process of discernment look like?

The process of discernment for a Christian should look similar to the process someone outside the church would take, with one exception. We involve God.

Prayer

It might seem like a waste of time, but an honest prayer could make all the difference.

First, we ask God to reveal the truth to us, even if it’s hard for us to handle. We ask God to open our minds and our hearts so that when the truth does come, we won’t shy away from it or fail to recognize it.

We also confess. God already knows what’s in our minds, so there’s no reason to be ashamed. It’s important we tell God what we want to be true. Owning our biases (and we all have them) helps us break down our defenses against truth.

What could like look like in practice? If my close friend has been accused of enabling abuse, I might pray to God and confess I don’t really want to know the truth. What I really want is proof that my friend is innocent. That’s a normal thing to want when someone we care about has been accused of doing evil. We want to remain comfortable in a world where we’re surrounded by good people. We don’t want to believe we may have been deceived by someone doing evil.

We need God’s help to clear our bias away.

Who has made the claim?

Next, we evaluate the person who has made the claim and how credible they are.

What exactly is the claim?

Can any parts of this claim be proven or disproven? If parts of it are disproven, which parts? There’s a difference between a minor detail (like the color of shirt a person was wearing) and a major part of the claim being disproven.

Where did this person get their information? Were they a witness or they did experience this firsthand? Is it hearsay? Do they have documents they can share, and are they willing to share them? Do they refuse to give details about how they know what they claim to know?

Has their dishonesty been exposed in the past?

What would this person stand to lose by making this claim? What would they stand to gain?

What would the people closest to this person stand to gain or lose by this claim?

What’s their agenda? This is an important one because we all have our agendas, and that’s not always a bad thing. If your agenda is to ease the suffering of people living in poverty, that’s a Christ-like agenda, but it’s still an agenda. You will be more likely to take actions that serve that agenda and less likely to take actions or make statements that would harm that agenda. If someone makes a claim that could harm their known agenda, that may be an indication they’re being honest. If someone makes a claim that furthers their known agenda, we need to evaluate the claim in light of that.

How has this person communicated their claim?

How much power, authority, or influence does this person have? Are they relatively safe while making this claim, or will this claim actually cost them something?

We have to look at the answers to these questions as part of the greater whole. Each answer is an indicator, but can’t be taken to prove or disprove a claim on its own.

Who is the claim about?

We can ask the same questions about this person.

In cases where a person who is not in a position of power makes an accusation of abuse against a person who is in a position of power, we can evaluate the claim and determine it’s most likely true. The cost of making that sort of allegation is huge and, in the absence of any outside interference, that person stands nothing to gain from making a false claim. Why would anyone risk making a false abuse claim against someone in a more powerful position?

In cases where both people have some measure of power, authority, or influence, we need to do more to evaluate any claims that have been made. In those cases, each may stand to gain something. We need to evaluate the integrity of each party and look at the people closest to each party to see if there are any identifiable agendas that could be served.

A police officer may accuse his superior of taking bribes but has presented no physical evidence of this. Maybe you know both men involved and are struggling to determine who to trust. In a case like that, it’s useful to ask these questions about both men to determine who is most likely to be telling the truth.

In the Church

We have to be willing to do this work within the church. It’s the only way forward.

It requires humility from us. We have to admit we might not be on the right side. We might not understand what’s going on around us as much as we think we do.

Most abuse cases won’t have physical evidence. Most of the time, it’s one person’s word against another. It’s especially challenging because we know how often abuse has been covered up and enabled in the past. We can’t rely on men in positions of authority to be honest or protect the vulnerable.

I believe there are good, honest men in the church, but the trouble is sifting them out from the filth. Carefully evaluating any claims we hear can help us.

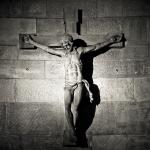

We’ve always known the church would attract evil. Jesus warned us.

Beware of false prophets, who come to you in sheep’s clothing, but underneath are ravenous wolves. By their fruits you will know them. Do people pick grapes from thornbushes, or figs from thistles? Just so, every good tree bears good fruit, and a rotten tree bears bad fruit. A good tree cannot bear bad fruit, nor can a rotten tree bear good fruit. Every tree that does not bear good fruit will be cut down and thrown into the fire. So by their fruits you will know them. (Matthew 7:15-20)

We have to be open to the possibility that someone who would otherwise be on “our side” could be part of the problem. We have to release ourselves from our biases and the desire to serve our own agendas to get at the truth. It’s uncomfortable and it creates such a stir of anxiety in us that we would rather duck our heads and wait for it all to blow over, but as baptized members of the body of Christ we must be willing to seek the truth no matter where that truth leads us.

This isn’t only applicable in cases of abuse. This applies every time we hear a claim and don’t have access to evidence.

We pray. We discern. We seek the truth.

We aren’t protecting the church when we refuse to see the truth. The church has survived just fine without you or me defending it. The truth is from God, and nothing from God can hurt the church.

What the church needs is a light that reaches into every dark corner. That’s how we protect the church.