A Review of When Francis Saved the Church, by Jon Sweeney

(This review is part of the Patheos Book Club.)

by Wendy Murray

When I was living in Assisi, Italy to work on my book about the life of Saint Francis of Assisi — titled A Mended and a Broken Heart — a friar and scholar with whom I regularly consulted exhorted me with a statement I have never forgotten: He said, “Francis is an ocean–don’t say we caught him.”

In this way I am always curious to read new books about Saint Francis and how others go about interpreting the life that, for at least one Franciscan friar and scholar, proved equally life-giving and elusive. Jon Sweeney’s new book, When Francis Saved the Church, is the most recent offering. Sweeney is no stranger to Franciscan studies, nor to Francis himself. He has written many books and serves as a consulting scholar for national news media.

Yet reading his new book I have been left to conclude — in keeping with the ocean metaphor– that if Francis is an ocean, then Sweeney and I caught glimpses of him at differing swells. His book bespeaks a Francis of bland generalities–a good listener, averse to seeing “the other” in people, Buddhist-like in his disposition toward creation. In contrast, the Francis I came to know and appreciate in the writing of my book, while congenial, nevertheless stood in stark contrast to these generalities; he was visceral, at times impulsive, emotional, and a man of action and conviction. He laid his life on the line numerous times without flinching, and, as Chesterton said it in his biography of Francis, “he threw his heart on to every raging fire.” As I described him in my book: “Francis didn’t operate on a linear plane. He blew apart in every direction at once.”

Of the wide swath of ideals Sweeney ascribes to Francis, the one that rang most true to me was Francis’ unequivocal conviction that orthopraxy trumped orthodoxy: “Francis watched his contemporaries in religious life . . . focus their ministry on teaching right belief, and in stark contrast he focused entirely on right action.” (21)

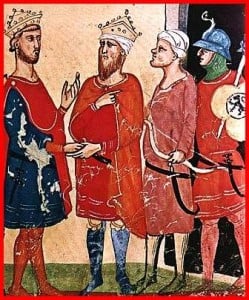

Beyond that, there is little in Sweeney’s portrait that I recognized. By way of example, I highlight only one episode because of its relevance today and also because it captures the ambivalence I felt reading Sweeney’s presentation of Francis of Assisi. The event is Francis’ trip to Damietta, Egypt in 1219, during the Fifth Crusade and his visit to the (Muslim) Sultan. Sweeney writes:

“. . . when Francis traveled to Egypt at the height of Christian crusading fervor, he angered nearly every religious leader of his day by asking questions and seeking to understand. What was there to discuss? many thought. A holy war has only one righteous side. But Francis understood through relationships the sort of things that only a few understand. He possessed an openness that was unique among his contemporaries. It’s almost as if Francis couldn’t see the differences between himself and the sultan, Malik al-Kamil, nephew of the great Saladin. To Francis, there was no ‘other.’ ” *

The author correctly concludes that, once the two came into one another’s company, Francis and al-Kamil forged a positive repartee and enjoyed mutual fondness and respect. Even so, there are several points in the description above that struck dissonance with me and the research I did on the same episode.

More Afoot Than Crusading Fervor

When Francis made his plan to travel to Damietta, Egypt, more was afoot than “Christian crusading fervor.” He, along with his traveling companion Brother Illuminato, intentionally calculated their journey to put them head-long into epicenter of the Fifth Crusade, dispatched by Pope Honorius IV in 1219.

On his way he first met with his religious counterparts, other Francsicans, including Brother Elias, in Acre (then in Syria, now in Israel), who supported him and traveled on with him to Egypt. Once there, they encamped with the Christian army where Francis became intimately connected to the second in command, the renowned King of Jerusalem, military leader and grand knight, Jeanne di Brienne. Francis consulted him regarding both the impending military campaign and his own desire to visit the sultan. (Jeanne di Brienne developed such a bond with Francis, that when he died, he requested burial in the basilica in Assisi, near Francis, wearing a friar’s tunic.)

Sweeney correctly makes the point that Francis did not go on the crusade as a warrior. Though, it is important to note that there was a day he would have (and did) fight fiercely in battle. Prior to his conversion he had actively pursued knighthood in no-holds-barred military engagments.

On this occasion, however, Francis was a knight for the gospel of peace. And, while on one level, it could be said that Francis was “open” in his visit the sultan — and there can be little doubt Francis comported himself with his signature disarming congeniality — his purpose was defined and singular. His official biographer Bonaventure and all major biographers (Thomas of Celano, Julien of Speyer; Henri D’Avranches; Jaques de Vitry; along with the author of the Fioretti, etc.) make it clear: Francis went on this crusade determined to visit the Muslim leader al-Kamil to try and convert him to Christ, even if it meant death, as all deemed it would. For Francis, there would be no point in making the journey and assuming its risks simply for the purposes of an open discussion.

In typical fashion, Francis (again) put his life on the line and threw his heart on this raging fire, offering his life for the soul of al-Kamil. Interestingly, this very earnestness and singleness of purpose won the affection of the sultan, and ultimately won Francis his freedom.

After Francis and Illuminato had been captured, threatened with decapitation, and then led into the presence of the sultan, he promptly asked Francis if he wished to become a Saracen (Muslim). Francis responded he did not come to convert to the religion of Mohammed, but instead had come to present the sultan’s soul to God on behalf of Christ.

The sultan, flummoxed, fetched his sages for advice. The sages told the sultan that he was obliged to uphold “the sword of the law” and was bound by duty to cut off the clerics’ heads. The sultan conceded that he was indeed bound by law to execute Francis and Illuminato. However, he decided to act against his own law, because, he said, “it would be an evil reward to bestow on one who intentionally risked death in order to save his soul for God.”

The Definite ‘Other’

Sweeney asserts in his book that, during this meeting, it was “almost as if Francis couldn’t see the differences between himself and the sultan. . . . To Francis, there was no ‘other.’ ” Neither Francis nor the sultan glossed over the differences between them. To the contrary, they confronted and defined them right-off-the-bat, but with humility one toward the other.

By the end of their visit, when it became evident that al-Kamil would not be converting to Christianity, nor Francis to Islam, with genuine good will the sultan invited Francis to extend his stay. Francis graciously declined stating that he and Illuminato would prefer to return to the Christian camp. Al-Kamil granted them safe passage and, on top of it, offered them gold, silver, and silk garments, all of which Francis refused. (He said that he considered the sultan’s soul to be the most precious possession he could have returned to God—much more so than the treasures.)The sultan gave the friars more than enough food and dispatched a military escort to guide them back to the Christian army.

While there was great “openness” at this meeting, the intent had always been clearly defined, both in Francis’ mind and also in al-Kamil’s. The ‘other,’ on the part of each, was duly noted and confronted. Each, however, did so with generosity of spirit. Some — and here it was difficult for me get Sweeney’s sense — would have preferred a Francis who acknowledged Islam as equal to Christianity and Judaism as among the world’s primary belief systems. But Francis did not do so. Others would like to have seen Francis condemn the beliefs of Islam altogether, which he also did not do. Francis set his own agenda in this encounter and followed it through on his own terms.

Rather than denounce the sultan for his beliefs, he put his own life on the line to offer to deliver the sultan’s soul to God through Christ. Risk and disgrace did not matter and the sultan understood this. In the end, the gesture won him, if not to conversion, to mutual respect and reciprocity of valor.

So here at last, as the Christian and the Muslim part company in mutual affection, the ocean that is Francis settles to an equanimous plane: Sweeney’s Francis and the Francis I know come together in agreement — Francis was loving toward and loved by all.

Historical Turning of the Tide

Sweeney concludes that “nothing really happened between Francis and the sultan in any historical sense.” Yet it could be argued that history indeed was made as a result of this meeting. In 1229, three years after Francis died (1226), al-Kamil negotiated a ten-year peace agreement with the then Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, who grew up in Assisi and knew Francis well.

Frederick had obliged Pope Gregory IX to mount the Sixth Crusade and al-Kamil, for political reasons of his own, wanted to avert the conflict. So he made the concession and surrendered the city. (The only other time Christian forces held Jerusalem occurred during the first Crusade in 1099.)

Other than this stunning historical moment, the only other point of commonality Frederick and al-Kamil shared was their independent acquaintance with their friend, a humble friar, who, by the time of the Jerusalem agreement, had been dead for three years.

Saint Francis was a little of what Sweeney contends him to be. But he was so much more than that. The Francis I know, whom I discovered in my years of research, was a “a complicated man, a true Italian among Italians, a poet, a warrior, a knight, a lover, a madman — and a saint.”

~ ~

* “Other,” in this context for Sweeney, means the great divide between Christianity and Islam that fueled the Crusades: ‘In the late medieval worldview the greatest ‘other’ was the follower of Islam. Muslims were sworn enemies of Christendom.’ (57)”