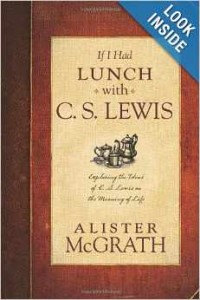

Alistair McGrath’s new book If I Had Lunch with C.S.Lewis is a short volume with a lively tea-and-biscuit feel that explores Lewis’s ideas on subjects related to the struggle and beauty of faith.

The book’s casual presentation could be helpful to some, but I stumbled over it. The issues addressed in Lewis’s arsenal of thought are not tea-and-biscuit fare. When Lewis himself broached such matters– heaven, education or suffering, it typically involved book-length discussions and years of evolving thought. I am not convinced this format serves Lewis or the reader. Even so, McGrath has earned his place in contemporary Christian historiography (including a recent fascinating biography of Lewis), so I tip my hat to him and wish him success with this small volume.

I focus upon here the chapter titled “Coping with Suffering: C.S. Lewis on the Problem of Pain.” In this short chapter McGrath highlights the two formidable titles for which Lewis is best known on the topic: The Problem of Pain and A Grief Observed. Each book was written at separate stages of his life and McGrath helpfully clarifies the distinctive elements of each: the former is clinical, deductive, analytical, and cogent — and the latter is visceral, dark, existential and at times random.

Lewis’s goal in writing The Problem of Pain, says McGrath, “is to ‘solve the intellectual problem’ that is raised by suffering.” Lewis makes the point that suffering is “built into the structure of the universe. But it is also something that God saw as a means of perfecting his creation.” Amid the darkness, Lewis asserts, there are distinct “chinks” of light, which, faint though they may be, help the lost person to carry on and believe that some larger operating principle is at work. It might be better understood this way: a person is lost inside a dark room who can not see the details of his surroundings — perhaps only indistinct shadows occasionally — but who knows, in spite of the darkness, that there is a floor to walk upon and walls that surround him.

One feels the rub when this reality works itself out the intimate drama of a person’s life. Here we have at once the universe with pain built into it and a solitary human heart being crushed by it and trying to find something to hold on to.

This was the vantage point of Lewis’s A Grief Observed, written in the aftermath of the death of his wife, Joy Davidman. This short volume reflects a dark and troubled Lewis. He is floundering: the rug has been pulled out from under his otherwise well-reasoned universe. Chinks or no, he doesn’t know how to navigate the darkness.

McGrath ultimately concludes that, despite the difference in tone, there is no major theological difference between these respective versions of suffering as articled in each of Lewis’s books. They are separate, if circuitous routes that ultimately lead to the same destination. God has intimate dealings with humanity and part of that picture involves inexplicable suffering. It is a contradiction that nevertheless holds: God is near and the world is dark. Or, another way of putting it, to quote Lewis’s personal literary champion, George MacDonald, “the veil between, though very dark, is very thin.”

At one point McGrath ponders, “. . . interesting, . . . but does it solve anything?”

No, it doesn’t. The problem of pain cannot be “solved” and there is no antidote for the weight of grief.

The best that can be gleaned from Lewis’s rational and visceral investigation, sketched out by McGrath, is that God entered the world save his creation and in so doing confronted the world on its own terms. This meant he would be crushed. Since Jesus was the embodiment of all that is good, a universe with pain built into it (according to Lewis), inevitably would contest that force of good. But is such knowledge enough?

Lewis would say, of course it is enough! In fact, it is the prototype. You find you way through your suffering because Jesus bushwhacked the way through ahead of you. More, he’s finding you in your suffering, and moving things around to give you ground to stand upon. He extends his hand to you in an invisible way and is asking you to take hold of it. To trust him.

~ ~

If I Had Lunch with C.S.Lewis is a selection of the Patheos Book Club. For more information or to join the conversation, visit here.

If I Had Lunch with C.S.Lewis is a selection of the Patheos Book Club. For more information or to join the conversation, visit here.