John P. Dourley is my favorite interpreter of Jung. Author of numerous books on Jung, including A Strategy for a Loss of Faith, The Psyche as Sacrament, and On Behalf of the Mystical Fool: Jung on the Religious Situation. You can read a couple of his essays online: “The Foundational Elements of a Jungian Spirituality” (Scribd) and “Jung and the Recall of the Gods” (.pdf). My favorite, however, is his book, Goddess, Mother of the Trinity (1991). Unfortunately the book is out of print and hard to find in libraries. I was fortunate enough to track down a copy at the Chicago Public Library. So I thought I’d give a summary of it here.

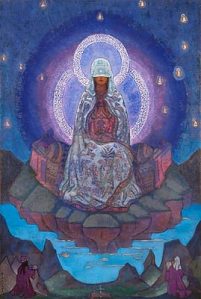

Following Erich Neumann, Dourley offers a Jungian interpretation of “the Goddess” which equates the archetypal Mother Goddess with the unconscious. The unconscious is defined as that “unlimited and creative largess” which is the “deepest ground of the psyche”. According to Dourley: “Culturally we are an uprooted people because we have lost living touch with her vivifying and unifying energies.”

This creative “matrix”, the unconscious, seeks to become fully real-ized (made real) in consciousness or the ego, which Dourley (following Jung) describes as its child. The Goddess, thus, gives birth to her child, consciousness, so that in the child she may come to know herself.

“The consciousness thus born moves, in the life of the individual and of humanity collectively, by the native rhythm of the psyche itself toward a sympathy as extensive as the embrace of the matrix mind which creates it and, in turn, seeks to become fully conscious in it. … In this manner does the mother of all consciousness seek to become real in each individual centre of consciousness in a process of mutual completion.”

The symbol of the Goddess and her child expresses well the relationship between consciousness and its divine matrix (the collective unconscious) as one of organic unity. Following Jung and Neumann, Dourley’s understanding of this deepest dimension of the psyche is best expressed by images of maternity and creativity.

However, this “birth” is not a one-time event, for the birth of consciousness is always necessarily partial, never total. The “inexhaustible creativity” and “infinity fecundity” of the Goddess seeks ever greater fulfillment through its expression in the human consciousness. The wholeness of the Goddess “can never be more than approximated in history.” According to Dourley, the claim that any one religious constellation exhausts this process of revelation is the substance of “psychic idolatory”. Consciousness must, therefore, always return to its source in the unconscious in order to expand the scope of its “empathy”.

According to Dourley, re-entering the womb of the Great mother is a “universal psychospiritual necessity”. The child, thus, must return to its mother, the Goddess. This return to the source is conceptualized as either a marriage with the Goddess (an incestuous one) or a return to the womb: death (self-sacrifice), followed by a rebirth. Dourley describes the unconscious matrix as “she who creates, destroys and renews human consciousness”. Thus the Goddess is not only Mother, but also Lover and Destroyer (see Robert Graves’ The White Goddess). The cyclical process, called “individuation”, repeats itself again and again in the psyche (both individual and collective) in an organic and dialectic process of ever-increasing mutual self-completion. In this reciprocity, the individual is redeemed through the ingression into the Goddess, and the Goddess is redeemed through her manifestation in the individual, or rather through her “progressive incarnation in existential life.”

This movement alternates between separation and reunion of the unconscious and consciousness, the Goddess and her child, which is perceived by the conscious ego as birth and death, respectively. When successful, this re-entrance into the Mother’s re-creating depths and the subsequent return to consciousness becomes the rhythm of a person’s life, a cyclical movement into into and out of the divine matrix which Dourley describes as “the ego’s love affair with the Great Goddess”.

The process is driven teleologically toward an ultimate and complete union of the ego and the unconscious, toward a wholeness which Jung calls the “Self”. Through each cycle the unconscious becomes progressively more incarnate in consciousness, and the scope of consciousness’s “empathy” increases. The move toward wholeness is a “paradoxical combination of greater personal integration and extended universal empathy.” According to Dourley, the goal of this development of consciousness is not perfection, but rather “completeness”.

Ironically, however, this process of increasing completeness demands the periodic death of the conscious ego. The ego

“constantly dies in its conflicted and restricted consciousness toward patterns or resolution of opposites and broader, more encompassing empathies, in a process that can never be completed in a lifetime, but can never be avoided without the sin of self-betrayal.”

Mythologically, this process is revealed in the numerous myths of dying gods and goddesses (or heroes and heroines), i.e., Ishtar, Osiris, Ba’al, Odin.

It is the desire to resolve the oppositions inherent in the conscious life which drive the ego to its death. These oppositions are manifest in myth as the slayer of the dying god or hero, he who is the dark twin of the god, both the same and “other”. In the womb (or the underworld), the god or the hero discovers “the unifying symbol which bears to consciousness the energies and more embracing empathy of resurrected life”.

But two pathologies can interfere with this process. While there is a healthy “nostalgia for the source from which we came” which pulls the ego toward the feminine and toward death, there is also a pathological

“refusal or inability to return to the conscious world with the re-creational energies given by the Goddess. As Jung explains, ‘As the Godhead [Goddess] is essentially unconscious, so to is the man who lives in God[dess].’ This is the fate of the addict and the truth of the mystic. The former can get in but not out. The latter can do both.”

“Consciousness once immersed in its transforming origin, must resist the temptation to give itself forever to her enticing dissolution.”

On the other hand, there is also a resistance to the return to the source, as it requires the ego “to forego the comfortable certitudes of a perspective, often gained with considerable pain.” The extreme form of this resistance is what Dourley refers to as “patriarchal consciousness”. It is

“every form of consciousness which prefers to remain within itself, to rely exclusively on its rational powers and willful energies and, so, to refuse the invitation of the Goddess to death and renewal in a life-long process with which the ego can and must co-operate but never control.”

This “refusal to re-enter the womb” is manifest in the myths of those gods and heroes who refuse the call of the goddess, i.e., Gilgamesh, Jehovah, Cuchuclain. Elsewhere, Dourley writes that, in Jungian terms, patriarchy “describes the pathological consciousness of members of wither gender when their conscious mind is severed from its roots in the archetypal and so divested of the experience of humanity’s native divinity.”

According to Dourley, in emphasizing the reality and power of the collective unconscious, Jung

“opened up to the twentieth century the possibility of the recovery of the Goddess which, when fully appropriated, can make less radical understandings of her nature and power look trivial and, when depicted as one among many deities rather than their common source, self-defeating.”