Over at the Heathen blog, Jön Upsal’s Garden, the (unnamed) writer of the blog has addressed “A Question for John Halstead”.

His question is essentially “Why the heck do you call yourself Pagan?” Since I don’t know the author’s name, I will call him Jön. Jön’s question is a genuine one, and it is one I have heard several times in the last few weeks. Jön’s question is addressed not just to me, but to other atheist Pagans and Humanistic Pagans out there, so I encourage others to post their responses as well. And to that end, I will be cross-posting this response on the HumanisticPaganism.com blog next month. The blogger, NaturalPantheist, and social media coordinator for HumanisticPaganism.com has already posted his response here.

So the question is: Why do we call ourselves “Pagan”? Why not just call ourselves atheists or humanists? What does the “Pagan” label add to our identity? Implicit in Jön’s question is the assumption that the term “Pagan” implies a belief in the literal existence of gods. And it is that assumption that I need to address first.

1. Theism was never a necessary element of contemporary Paganism.

I guess it makes sense to assume that all contemporary Pagans must be polytheists, given that ancient pagans were polytheists. But I have always found this assumption to be odd, given the history of the Neo-Pagan revival. Following Sarah Pike, author of New Age and Neopagan Religions in America, I date the beginning of the Neo-Pagan movement to 1967, which was the year three of the most important early Neo-Pagan groups were organized. In 1967, Feraferia was incorporated, the New Reformed Order of the Golden Dawn was founded, and the Church of All Worlds filed for incorporation. Literal belief in gods was not a requirement for membership in any of these organizations. Even if you date the Neo-Pagan revival earlier to Gerald Gardner, literal theism was not a requirement for British Witchcraft either. Even modern Heathenry (which also began in the 1960s) was historically ambivalent about the nature of the gods.

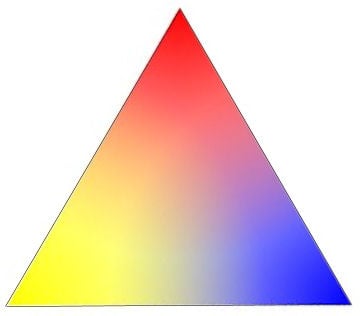

In any case, since that time, Pagans have always held a wide variety of beliefs about the nature of Pagan deities. Margarian Bridger and Stephen Hergest have famously described Pagan theology as a multi-colored triangle with three extreme positions which subtly blend into one another. The red corner represents the view that the gods “are personal, named, individual entities, with whom one can communicate almost as one would with human beings.” The blue corner represents the view that the gods are “humanlike metaphors or masks which we place upon the faceless Face of the Ultimate, so that through them we can perceive and relate to a little of It.” The yellow corner represents the view that the gods are “constructs within the human mind and imagination.” Atheistic or Humanistic Pagans tend to fall more into the yellow part of the triangle.

Bridger and Hergest’s model was published in the first issue of The Pomegranate in 1997. But atheistic/humanistic Pagan is much older than that. Writing in 1979, Margot Adler observed in Drawing Down the Moon that, for some Neo-Pagans, the gods are “not to be believed in or trusted, but to be used to give shape to an increasingly complex and variegated experience of life.” In fact, nowhere in Adler’s opus is there any indication that belief in literal gods is a necessary element of Paganism. Reading Drawing Down, it is possible to walk away with the impression belief in literal gods is more the exception than the rule among Neo-Pagans. Maybe this is a reflection of Adler’s own bias, but she was a professional journalist, so I’m inclined to believe her.

Another useful way of thinking about this is the Three Centers model of Paganism, which views Paganism as a Big Tent with three “poles”: Nature, Deity, and Self. Individuals may find themselves closer to any one of these poles or anywhere in between. So a Pagan may identify with the Nature or Self pole (or both) and not with the Deity pole at all and still be a Pagan.

2. Not all contemporary Pagans are reconstructionists and not all ancient paganism was theistic.

But what about the ancient pagans? Didn’t they believe in literal gods? It is difficult to say what exactly ancient pagans believed about the nature of the gods. The terms “theistic” and “atheistic” are products of a post-Enlightenment culture, and we should beware of projecting our categories backwards onto peoples far removed in time and space from us. But even if ancient pagan were theistic in the sense in which we understand it, not all contemporary Pagans are trying to reconstruct the ancient pagan past.

Isaac Bonewits famously distinguished between Paleo-Pagans, Meso-Pagans, and Neo-Pagans. A fourth category might be called “Retro-Pagans”. In contrast to Retro-Pagans or pagan reconstructionists, Neo-Pagans attempt to blend what they think were the best aspects of ancient pagan ways with modern humanistic, pluralistic, and inclusionary ideals. Polytheism may are many not be among the elements which Neo-Pagans choose to include in this blending. Humanistic Pagans, for example, draw inspiration from ancient pagan myths and rituals, but attempt to do so in a way is both intellectually and emotionally satisfying to modern people. As a result, some Humanistic Pagans may use theistic language in a metaphorical or Jungian sense, while others exclude theistic language from their practice altogether.

It is also important to note that, atheism was not unknown among the ancients. Humanism, philosophical naturalism and paganism have a shared history, spanning centuries. Both humanism and naturalistic science flowered in Classical Greece, for example. While they declined throughout the Christian Middle Ages, they enjoyed a resurgence during the Renaissance, which also saw a renewal of pagan imagery and symbolism. Some ancient pagans — like the Stoics and the philosopher Plutarch — adopted allegorical interpretations of their myths and metaphorical understandings of the gods. See, B. T. Newberg’s Naturalistic Traditions series, Luc Brisson’s How Philosophers Saved Myths: Allegorical Interpretation and Classical Mythology, and Anne Bates Hersman’s Studies in Greek Allegorical Interpretation.

3. Paganism adds a emotional element to philosophical naturalism.

Now, to answer Jön’s question, What does Paganism add to humanism or atheism? For me, it adds an emotional quality. It speaks to the parts of my being that rationalism does not reach. Many religious humanists and religious naturalists, like myself, find humanism and philosophical naturalism to be intellectually compelling, but emotionally or psychologically unsatisfying. Humanism and naturalism just lack the symbolic resources of theistic religions. Paganism is well-suited to fill that void. On the other hand, contemporary Paganism can seem prone to irrationalism and superstition. Scientific naturalism can counter this tendency. Together, they balance each other. Naturalism can help keep Paganism true to the empirical world around us, while Paganism can enrich naturalism with symbolism and myth.

A good example of this approach is Áine Órga’s essay, “Emotional Pantheism: Where the logic ends and the feelings start”. Áine writes that while she does not believe in divinity in any real way, she has very strong pantheistic feelings:

“My beliefs and therefore my practice are certainly naturalistic. I leave room for the unexplained, and engage in practices that might seem empty or pointless to some naturalists or atheists. But I don’t take many leaps of faith intellectually, everything is based in reason. In this way I am a naturalistic Pagan.

“Where I do take those leaps of faith is in the emotional sphere. By engaging in this spiritual practice, I open myself up to experiencing things beyond the mundane. In many ways, it is in exercise in allowing myself to feel without judgement. My spirituality is my way of allowing my pantheism a space in my life.”

And atheistic or Humanistic Pagans like me find Pagan myth and symbolism — both contemporary and ancient — to be especially significant. For example, the Neo-Pagan Wheel of the Year with its corresponding mythology has a deep emotional and psychological resonance for many atheistic and Humanistic Pagans. The Neo-Pagan Mythos is an amalgam of myths and stories drawn from many different sources, both ancient and modern. It describes the passion of dying and reviving deities and heroes, often including the monomythic journey of the hero and the interaction of a tri-form goddess of nature and sovereignty who is wed to a duo-form phallic consort/sacred king with light and dark aspects, who perpetually struggle with each other, sow the seeds of their own rebirth, and are ritually sacrificed to or by the goddess in a cyclical pattern in order to renew the powers of life. This Mythos emphasizes those aspects of the deities which relate to sex and death, which have been excluded from or demonized in the monotheistic religions, and invests these traditionally negative qualities with positive meaning, including the valorization of the divine feminine generally, and especially the dark aspect of the divine feminine which gives death in order to generate new life; and the wild or bestial phallic/horned god of sexual license liberation.

4. Nature and ritual are two of my spiritual touchstones.

The experience nature as sacred is at the heart of why I call myself Pagan. Emma Restall Orr’s definition of a “Pagan” as “one for whom that ancient wordless book of lore, nature, is utterly sacred and as such, s/he listens more carefully, treads more softly, and celebrates with more exuberance” fits me well. And this is consistent with how the word has been used by many others, include the Romantics and Transcendentalsists. Jön asks:

“Is it to mark their belief in the importance of nature? That doesn’t work, because there are plenty of environmentalist atheists. I’d be willing to bet the intersection between those two groups was pretty significant, actually.”

Jön is right that there are many environmentalists who are atheists. I see Paganism as a form of what Bron Taylor calls “Dark Green Religion” which brings to secular environmentalism a sense of the nature’s sacredness. A purely secular environmentalism would be unsatisfying to me in the same way that a purely secular humanism would be.

Jön goes on:

“Is it about the rituals? Well, here he might have something, if he’s just looking at rituals as psychodrama (although I’m sure he won’t enjoy being reminded that Anton LaVey got there first in his Satanic Bible and Satanic Rituals). But if it’s about the plain efficacy of ritual, it still doesn’t explain why he doesn’t take the final step and just start his own religion, with its own rituals that hit the psychological buttons he feels are their purpose, but which doesn’t rely on any supernatural agency for its undergirding premise, and thus distance himself from those Gods-believers he seems to despise so much.”

I don’t think its any coincidence that the publication of LaVey’s Satanic Bible in 1969 coincided more or less with the Neo-Pagan revival. (I don’t think he “got there first”, though.) Both groups were on to the same idea of ritual as “psychodrama”.

For me, one of the the goals of Neo-Pagan ritual is to evoke powerful emotional responses for the purpose of incarnating, exploring, and consecrating the archetypal patterns of my unconscious, so as to resolve those intrapsychical conflicts which were created by the dissociation of the shadow components of my psyche (sex and death) caused by Western guilt culture generally and my monotheistic upbringing specifically, and to effect a healing reintegration of those elements.

I also use ritual to connect with nature and try to alter my consciousness to experience an expanded or deeper sense of “Self” which includes all living beings — an experience which is sometimes called the “re-enchantment of the world.”

This perspective is consistent with what some early leaders in the Neo-Pagan movement described as the purpose of ritual:

“We are talking about the rituals that people create to get in touch with those powerful parts of themselves that cannot be experienced on a verbal level. These are parts of our being that have often been scorned and suppressed. Rituals are also created to acknowledge on this deeper level the movements of the seasons and the natural world, and to celebrate life and its processes.” — Margot Adler

“The purpose of ritual is to wake up the old mind in us, to put it to work. The old ones inside us, the collective consciousness, the many lives, the divine eternal parts, the senses and parts of the brain that have been ignored. Those parts do not speak English. They do not care about television. But they do understand candlelight and colors. They do understand nature.” — Z. Budapest

5. We’re all just making it up anyway.

To answer Jön’s question why we don’t just create our own religion with our own rituals — I think that’s exactly what a lot of Neo-Pagans are doing! Many Neo-Pagans recognize that all religions are, on some level, invented. But rather than causing us to reject all religion, we embrace it! As Paul Chase was written in his thesis, “Neo-Paganism: A Twenty

Finally, Jön asks whether it wouldn’t be simpler to drop the “Pagan” label, so I wouldn’t have to keep explaining all this. I admit, there are days it is tempting to do so. But I think it is a mistake to believe that any label I might give myself would eliminate the need for explanation. Christianity is the majority religion in the United States, for example, but given the wide variety of definitions of “Christian”, people still have to explain what being Christian means to them. So I will go on calling myself “Pagan” and explaining why to those willing to listen.