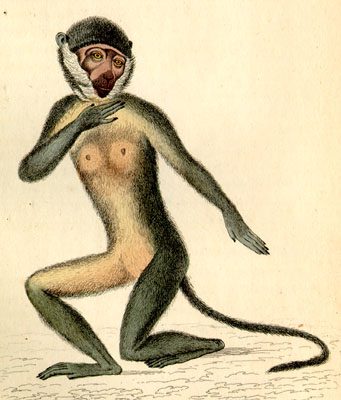

Man is a self-glorified ape. He occupies no special place in the Cosmos — a bigoted, specieist idea — and the differences between him and his hairier, happier relatives are merely quantitative. Man has more intelligence as he has less hair than the gorilla, and this alone is the reason for his apparent apartness from the animal kingdom and his puffed-up sense of dominion over the earth.

The ape uses rudimentary tools to feed itself. The human uses complex tools to feed himself. The ape lives in a basic society,  complete with leaders, followers, mates, family members, and even friends. The society of man is a more intricate version of the same. An ape can solve simple puzzles. A man can solve complex puzzles. The difference between the two is the same as that between a Model T and a Lamborghini, a sapling and an oak. The human represents a quantitative improvement over the capacities of the orangoutang. He does not dwell in a entirely separate and elevated sphere of existence.

complete with leaders, followers, mates, family members, and even friends. The society of man is a more intricate version of the same. An ape can solve simple puzzles. A man can solve complex puzzles. The difference between the two is the same as that between a Model T and a Lamborghini, a sapling and an oak. The human represents a quantitative improvement over the capacities of the orangoutang. He does not dwell in a entirely separate and elevated sphere of existence.

This belief has half a billion benefits, chief among them this: If we are not unique from beasts, then our complicated practice of morality is merely a social and evolutionary construct, as are the varied practices of the animal kingdom. Though the moral construct may be complex and even useful, ultimately it — with its mandate to monogamy, charity and all the rest — may be disregarded with the same ease of mind as one casts aside any other social and/or evolutionary construct, like eating three meals a day instead of whenever we’d like to eat.

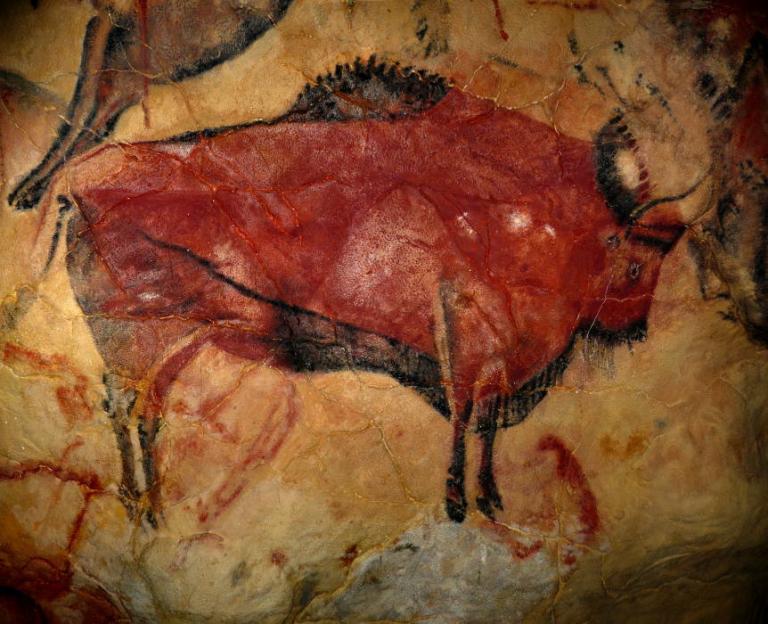

As someone who loves to sin as much as eat whenever I want, I’d snap up this belief like pike does a mackerel if not for those damn cave-paintings in those stupid caves.

By them, man exhibits a characteristic that can only be described as a quantum leap, a qualitative difference between himself and the beasts, a “1” where the animal is set at “0”, not a “2” where the animal is set at “1”. Art. That man from our earliest knowledge of him is an artist is evidence of an infinite, insurmountable gap between him and his naked relatives. It is not, as was the case with tool-using, that the ape is a rudimentary artist and man a better one. No animal draws pictures. There is no art in the animal world, while it shines forth in mankind like a lighthouse in an otherwise murky sea, to the point that it is quite literally the first thing we know about prehistoric man. As the journalist G.K. Chesterton pointed out, “All we can say of this notion of reproducing things in shadow or representative shape is that it exists nowhere in nature except in man; and that we cannot even talk about it without treating man as something separate from nature.”

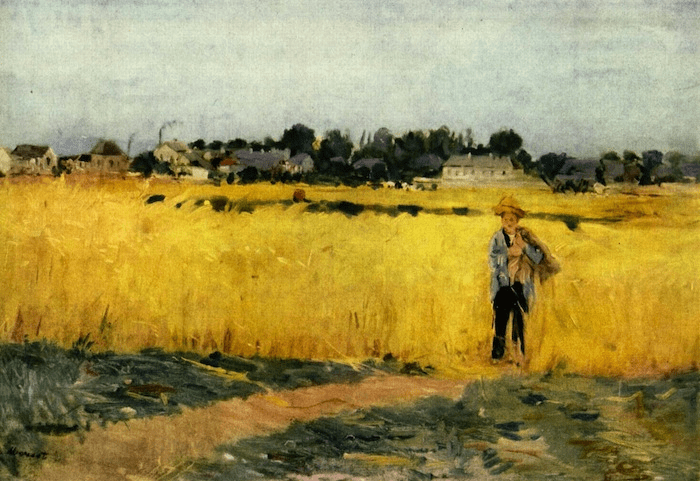

The fundamental reality of art is depiction. Modern art depicts something, even if that something is an intangible abstraction, and existential angst, or an otherwise frightfully modern emotion. But we’ll leave aside the moderns for the moment and focus on the majority of human depiction, which has been of objects, objects lit up with the glorious light of subjectivity — as in the Impressionists — or pushed towards an attempted objectivity — as with the Realists.

Here’s the crux: Depiction requires the ability to view the thing depicted as useless. This is a difficult concept to nail to a board, so allow me say the same thing in several ways, in the hope that one will ring: Art requires us to view an object outside of the normal realm of that object’s usefulness, to view a cornfield in the fact of its being, not just in the fact that it’s useful for growing food.

Art requires that we are able to experience and “speak” of something outside of its useful context, of the water outside of our thirst, the mate outside of our sexual need, and the cow outside of our hunger.

A peach, to us, is for eating, as it is for the ape. But only the human will depict that peach on the wall of his cave, as if it had value not simply in being eaten, but in the fact of being a peach.

If reality is viewed in terms of need-fulfillment, then art, which fulfills no need besides itself, cannot exist. If use is the method by which a subject views the universe, that same subject cannot take a step back and draw the universe, for art is useless. He cannot view the buffalo as being, just being, available to observation, disinterested admiration, love, or simple depiction, if the buffalo is merely useful for man.

If reality is viewed in terms of need-fulfillment, then art, which fulfills no need besides itself, cannot exist. If use is the method by which a subject views the universe, that same subject cannot take a step back and draw the universe, for art is useless. He cannot view the buffalo as being, just being, available to observation, disinterested admiration, love, or simple depiction, if the buffalo is merely useful for man.

This ability to interact with objects outside of their usefulness to us is evidenced by the fact that we interact with everything, while animals have a limited environment. I know about the Milky Way, the periodic table, and the country of Uruguay, things I have no use for. If the environment is given its scientific definition, “the air, water, minerals, organisms, and all other external factors surrounding and affecting a given organism at any time”, then humans have the remarkable ability to transcend their environment, while the ape continues to interact with its environment, and its environment alone, unless trained to do otherwise (i.e. unless something becomes incorporated into its environment through a system of rewards).

The advent of artistic creation is man, it blossoms in the Cosmos from that one, singular source. The human being stands alone, a being that can interact with the world outside of his environment. Thus the human being does indeed stand in a position at once apart from and elevated over that of the beasts. He has dominion over the world, because he is the only being within the cosmos that has a world, a whole world, while all other conscious life has an environment (by its nature limited).

It’s almost as if the world, in some strange and marvelous capacity, exists for him. But bottle the thought, its implications are drastic.