I’m in the habit of taking popular music at its word. That is, I take the thumping stuff as a general indicator of what our culture enjoys hearing, and as a direct result of this habit, I’m awash in an atlantic depression, considering moving off the grid to make moonshine in the company of two goats (as an isolated goat gets lonely and begins to yell for companionship).

There is a trend in the basic pop lyric which, if actualized into daily life, will have us all enthusiastically trying to enjoy the iciest bowels of Hell. It is the death of Eternity.

Now the word Eternity freaks us out because God freaks us out — and this is right and just, because both are terrifying — but it was not always the case that a denial of God’s existence necessitated a denial of Eternity. Frederich Nietzsche, for instance, had no problem furiously denying the existence of the Almighty while simultaneously reveling in glimpses and swoons of Eternity.

This is because an experience of Eternity is an experience of the inexhaustible. This is not a definition, but a metaphor. (I don’t dare nail down the ineffable Evermore with an all-defining, prosaic thump. I can only point out Eternity as I point out a star, holding a finger out to something I am absolutely sure of, hoping that by grace your eye will understand and follow the precise angle of my stretching finger 20 light-years into space.)

So yes, Eternity is the inexhaustible, the evermore, the cup that runneth over, the paradoxical experience of perfectly-never-enough, of Beauty — which we can never conceive too much of — of goodness and of truth. Considered as such, Eternity is not religious. Consider, for instance, the lovers.

Regardless of a belief in a Creator, lovers speak of “being together forever,” not as a sweet, whimsical nothing, but as rock-solid understanding of the fact that their love has bound them. This “forever” is an eternal word. Love will not “die” with the death of one of the lovers. Love exists beyond the material presence of its object. In fact, I would argue that forever-love is experienced as always having existed as a potentiality within the lover. If a man “falls in love at first sight,” it is only because love was already sprung like a tiger trap for him to fall in. “I loved you before I met you,” say the lovers, “I was waiting for you,” and “it was you I loved all along.” The two did not “make love” (in the non-biblical sense) upon meeting each other. Each call forth love from the other. But what can be called forth that isn’t already in existence? In basic human experience (I assume we still have it) love forever is, forever was and forever will be. It is not bound by space, time or reason. We can love a time we never knew, a place we’ve never been, a character — like Frodo Baggins — who has no real existence, an animal — like a goat — who doesn’t share our species, an enemy who is categorically unloved, and the child we have not yet born. Les Miserables had spoke a truth deeper than we give it credit for: To love another person is to see the face of God, for through eternity we meet Eternity.

Now I said Eternity was not religious, but all religion is a dealing with Eternity. This is phrased in a hundred different ways, my least favorite being — and this usually comes from the sensitive, religious depths of The Huffington Post — that religion has value because it makes you “part of something bigger than yourself.” This is a degradation of the fact — that religion is sinking your teeth into Eternity — that works to make it sound like the joy of religion is essentially the joy of joining a club. (Actually, other people has always seemed to me to be the worst, most difficult, most exhausting part of religion.)

No, the joy of religion is its confrontation with the inexhaustible. The religious claim is fundamentally this, that our glimpses of Eternity — in love, beauty, truth, sublimity, sorrow, and all the rest — have their source in one deep, deep Eternity, and that man was meant for these depths, not the shallows. (And because I know this to be true, I can say with confidence that Frederich Nietzsche was a profoundly religious man. (And because he’s dead, he can hardly rebuke me for it. (But if he is in Heaven, which I strongly suspect, he might just reward me for it by his intercession. (But if it’s Heaven, he already has. (Eternity, you know.)))))

Now if you were wondering what any of this has to do with popular music, I’ll be honest, I got excited about Eternity and forgot what I was writing about. To the point.

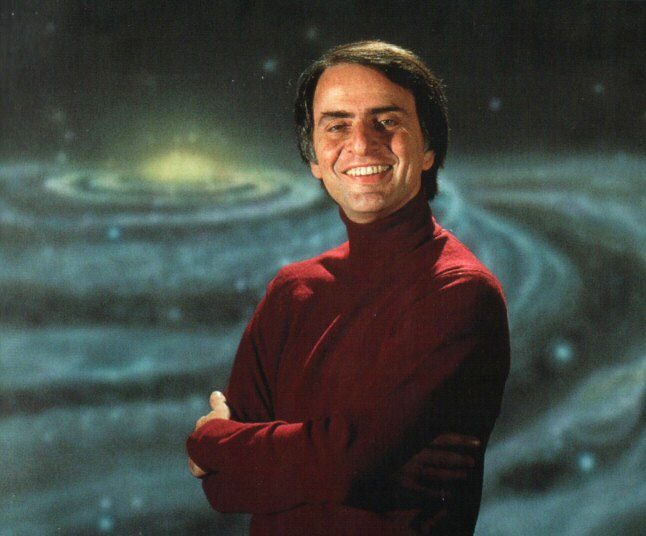

In a world in which science has dethroned philosophy as the primary — if not the only — method of attaining truth, the concept of Eternity is absurd. Science only deals with the physical universe, the material Cosmos which, in the wonderful words of Carl Sagan, “is all that is or ever was or ever will be,” and the primary fact of the material Cosmos is its crumbling. Science deals with a realm in which nothing remains, in which entropy is law and all things are move from order to disorder — from something to nothing. All things are exhaustible. If science is the only way truth can be known, Eternity is an illusion. That love — a chemical in the brain — could be a reality that transcends space, time and its object is an idiot’s idea. Science smiles obligingly on lovers who whisper “forever,” but she knows the truth: The lovers are lying.

This, I would argue, is one of the fundamental roots of our popular culture: a religious faith in science and technology as gods who can explain and fix everything. This faith is called scientism. It does not imply that people understand and use science well, just that they believe in it over everything else, and deny, or more typically don’t know, that it is rooted in philosophical and faith-based assumptions about the universe.

So what’s to be done in the face a universe emptied of Eternity? Suicide is a highly reasonable response. If nothing lasts, what’s the point of prolonging our inevitable dissolution, our ordained crumbling in a crumbling world? The world is essentially a difficult, suffering-filled trek in which everyone is executed at the end, and its hardly a shocking change of plans if we should take the Sunset Limited.

Nonsense, says the world, life is to be enjoyed, and the death of Eternity allows us to enjoy it for what it is. Look at us! We dip our toes in a cornucopia of goods and pleasures and there is no Judgment after death, no everlasting reality to face for doing what we want with them, as long as we’re not hurting others. The point of life is to be happy, so go, be happy, and yolo!

In the absence of Eternity, all we can do is attempt to imitate the Evermore by indefinitely repeating a finite good until we have a stroke and die. Joy shifts from finding inexhaustible depth in one thing to the heroic attempt to daily repeat a multitude of exhaustible pleasures and distractions and thus create an illusion of eternal life. This is where popular music makes an entrance.

Katy Perry needs to do Last Friday Night “all again,” Britney Spears tries to convince us she can “dance until the world ends” and Ke$ha reminds us that despite the “TiK ToK, on the clock,” “the party don’t stop no,” not because that’s in any way true, but because it needs to be true. So certain are the Black Eyed Peas of the necessity for indefinitely repeating their finite party that they actually resort to just straight auto-tuning the days of the week: “Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday / Friday, Saturday, Saturday to Sunday / Get get get get get with us / You know what we say / Party every day / Pa pa pa Party every day.” This song — “I Gotta Feeling” — might make the song “Party All The Time” — on the same album — seem unnecessary, but when your goal is to avoid despair by endlessly repeating an ever-ending thing, there’s really no limit to how often you can say it. The most repeated line in pop music is a bad attempt at Eternity: “All night long.” Pitbull takes it home, and God bless him for it. His mind-numbing repetition of “the party ain’t over, the party ain’t over / The party ain’t over” is to be expected, but the desperate necessity for a false sense of eternity truly blossoms in his album-topping “Don’t Stop The Party” in which we find out that “They can’t, they won’t, they never will stop the party/ They can’t, they won’t, they never will stop the party.”

And it’s this “they can’t stop the party” that I appreciate, not for its depth, but for its honesty. Truly, they can’t, for to stop the party — that conglomerate of finite pleasure — would be to face a world in which everyone, drunk or sober, having been laid or not, is about to die, with utterly no choice in the matter. The repletion of the finite as an illusion of Eternity is — of course — not limited to partying. It lives in the cult of youth which must by surgery and with-it-ness stay forever young, consistently and without reprieve propping up the pretense that the finite good of youth can be indefinitely repeated, which is, of course, another trope of popular music. It lives in the cult of wealth, which sees the continued and indefinite repetition of wealth-acquirement as an adequate replacement for finding the singular pearl of great price, that is, Eternity, and this is, again, a favorite topic of popular hip-hop. But why try and convince you of this when parody has already hit the nail on the head?