What are the differences and similarities between the Law of Hammurabi and the Law of Moses? Did one borrow from the other?

Ancient Law Books

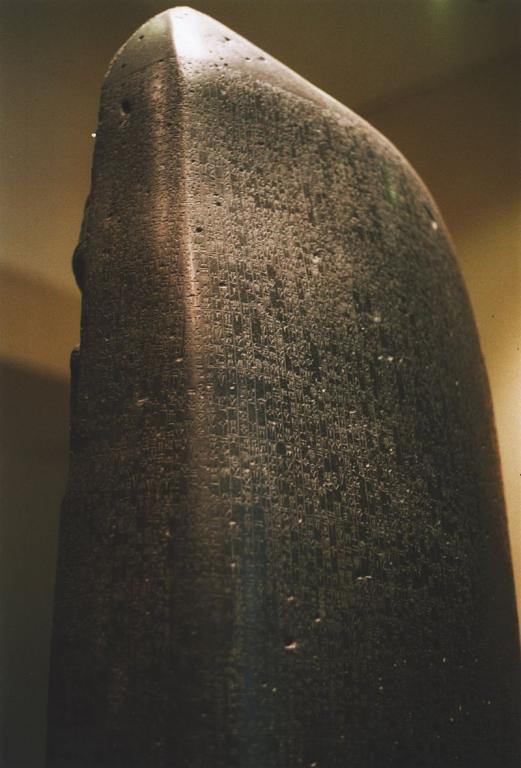

After ancient Israel’s exodus from Egypt, God gave to them the Book of the Covenant, a book which contained the laws of God by which Israel was to live. It is sometimes called the Law of Moses. Another ancient people, the Babylonians, had their own law called the Code or Law of Hammurabi. In reading both, we notice that there are striking similarities, but there are also vast differences. And the differences show how one is far superior to the other. The source of the Book of the Covenant is God; the source for the Code of Hammurabi ancient Mesopotamia, or Babylon to be specific. The Code of Hammurabi is a well-preserved Babylonian code of law by which the nation is to live by, so both are sets of laws designed to help society function in ways so that it could prosper, and these laws contained particular civil rights.

Similarities

The Book of the Covenant is sometimes called the Law of Moses, but the Book of the Covenant and the Law of Hammurabi used in the Babylonian Empire, seem closely related in the contextual and legal language, so it’s easy to see how the Covenantal Laws of Israel and other nations might have influenced one another. There is also a shared common purpose because both contain serious consequences for those who break which break the law(s), so the consequences act as a deterrent to crime. For example, both share in the protection of marriage, family, property damage, injury, murder, robbery, theft, kidnapping and even in commerce, so they both act as stabilizers of society. For Israel, they constituted expectations from God in how we are to live with our neighbors, and I personally see this as foundational for the U.S. and other nations because our laws encourage both citizens and authorities to live in relative peace. Both laws share similar expectations for society and for the stability of the nation.

Code of Hammurabi. Artist, Unknown

Differences

As for as differences between the two laws, the authority or source are different; one is from God and one from Hammurabi. One has reasons that are self-serving (Hammurabi), but God’s laws are always for the benefit of the people. In Martha Roth’s, The Laws of Hammurabi, she writes that Hammurabi felt that he was chosen by the god of Enlil, only one among many, to be made the shepherd of Babylon (lines i.27-41, p. 336). Moses knew that He was a chosen vessel of God, the One and True God, to be shepherd the nation of Israel. He was a shepherd when God called him, and died as one. Other differences concerned the violation of laws of Hammurabi which constitutes violations against Hammurabi himself and the nation, but violation of the Covenant are sins against God Himself, even though the people also had been sinned against. Different too was the fact that God was interested in creating a kingdom of priests, a holy nation, but Hammurabi’s motivation is for prosperity and longevity on the throne. Therein lies significant differences…the Covenant protects the disenfranchised members of society, regardless of their place or rank in society, while the Code of Hammurabi is interested only in the free men class and gives special protection to the middle and higher social classes of Babylon. This is seen in the laws of the Code as the awilu are given special status and protection but the lower classes, the wardu (slaves) and the mushkenu (free person of low estate) have no such protection. That makes the lowest classes of the Babylonian society significantly more liable. [1] While biblical law sees human life as more valuable than material possession, the Code treated significant material loss as sometimes worthy of death (Code of Hammurabi, p 338). [2] Conversely, God requires a life for a life, but the Laws of Hammurabi may only require financial compensation, and the life of a slave might only bring a fine. [3] I find it interesting that silver was the main currency of Babylon, but gold is the primary precious metal used in the inner sanctuary.

One is Superior

The superiority of God’s Laws is that obedience (and holiness) is the desired outcome, so that a relationship with God is made possible, but the Law of Hammurabi’s goal is for longevity of the king and prosperity for the nation, regardless of who gets hurt. For example, the death penalty for theft (Hammurabi) seems extremely harsh as compared to the Covenant which required restitution. The death penalty for thievery in Babylon seems to indicate that the nation valued goods over human life, while the Covenant valued people over things, not requiring a thief to die. Another example was when anyone caused a pregnant woman’s child to die. The Book of the Covenant required a life for a life while the Code required they pay a fine. This Code clearly indicates a lesser value on human life Covenant. God sees the sanctity of life…the Code does not.

The Law and Salvation

Both the Code and the Covenant share common ground in that they contribute to civility and order in society, and they bring criminals to justice, however, the Covenant stands supreme over the Code because of its Author Who is no respecter of persons. We cannot say the same for the Code of Hammurabi which had regard for a person’s social and financial standing. Paul understood that the law was a means of knowing what sin was (Rom 7:7), and the impossibility of presenting ourselves before a holy God, but thankfully, the New Covenant shows us that “the righteousness of God has been manifested apart from the law [and that] the righteousness of God [is] through faith in Jesus Christ for all who believe” (Rom 3:21-22). That is salvation. The Code has no such ability to make a person righteous because “one is [only] justified by faith apart from works of the law” (Rom 3:28), and no amount of law keeping could ever make one perfect. Even so, we should still strive to “uphold the law” (Rom 3:31c), but the good news is that even though we can’t possibly fully obey the law, since “all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God [we] are justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus whom God put forward as a propitiation by his blood, to be received by faith” (Rom 3:23-25a).

Conclusion

If it were true that ancient Israel copied and used the Law of Hammurabi for the basis of the Book of the Covenant, it begs the question; why did the Israelites only use some of their law and not all of it? They certainly didn’t take part of the Code that provided for the poor, widowers, and orphans. The Code had no such protection to help, protect, and defend those who could not help or defend themselves. Moses certainly didn’t copy the laws from the Code which favored the wealthy like the Law of Hammurabi had. What the Babylonians should have done was to copy the Book of the Covenant from Moses, because it didn’t have laws favoring the rich and powerful. This Book doesn’t place products over people. It regards the sanctity of life of infinitely more value than just paying a fine. That’s because it’s from the Author of Life.

Article by Jack Wellman

Jack Wellman is Pastor of the Mulvane Brethren Church in Mulvane Kansas. Jack is a writer at Christian Quotes and also the Senior Writer at What Christians Want To Know whose mission is to equip, encourage, and energize Christians and to address questions about the believer’s daily walk with God and the Bible. You can follow Jack on Google Plus or check out his book Teaching Children the Gospel available on Amazon.

1 In Babylonian society there were mainly three classes; the awilu, a free person of the upper class; the wardu, or slave; and the mushkenu, a free person of low estate, who ranked legally between the awilu and the wardu. “Babylonia Babylonian Social Hierarchy.” Bible History. http://www.biblehistory.com/babylonia/BabyloniaSocial_Hierarchy.htm (Accessed Oct 16th, 2017).

2 Desmond T. Alexander. From Paradise to the Promised Land (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Publish, 2012), 217.

3 Ibid., p. 219, 210.

Page numbers are cited from the assigned reading of Martha Roth, The Laws of Hammurabi.