How does the dynamism of analogy reflect itself in the ways we go about imaging God?

If you haven’t read the introduction to Przywara’s Analogia Entis, then pick it up again.

John Betz, author of After Enlightenment, has littered his exhaustive introduction to Analogia Entis with many nuggets from Przywara’s other writings, sermons, and letters.

Here’s a sampling from the introduction of a 1926 Przywara lecture:

“Thus all our wandering in Him and to Him is itself a tension between an ineffable proximity and an ineffable distance. Every living thing… everything that happens is full of His presence. ‘He is not far from us; for in him we live and move and have our being.’ But we grow in our sense of His fullness only in the measure that we do not equate Him with any created thing or circumstance, that is, in the measure that we stand at an ultimate distance from every particular shining of His face. He is the one who lights up before us when we stand at a distance, and who lights up before us to urge us on. He is the infinite light that becomes ever more distant the closer we come to Him. Every finding is the beginning of a new searching. His blessed intimacy is the experience of His infinite transcendence. No morning of mystical marriage is a definitive embrace of His fullness; no mystical night of despair a detachment from His presence… He compels us into all the riches and changes of world and life in order that we might experience Him anew and more richly as beyond this world and life. And, ultimately, this indissoluble tension of proximity and distance to Him is but the innermost revelation of his own primal mystery, by which He is in us and beyond us, closer to us than than we are to ourselves, such that we love him as proximity itself, and, yet again, farther away from us than any other distance, such that we revere Him with trembling as distance itself. God in us and God beyond us.”

Przywara is clearly riffing on Augustine’s “God is closer to me than I am to myself” (Book X of the Confessions if I’m not mistaken) in a way that brings out its dynamism.

Artur Grabowski, in his IMAGE (59) essay “Unapologetic Visibility” runs with this dynamism in a different direction while commenting on John Paul II’s Roman Triptych and Letter to Artists:

“Of course, it is possible to be mistaken in one’s image of God. Faith, blind or enlightened, is in no way like an insurance policy. It is in the risk of creating that the artistic process is tied to the process of coming to know the subject. But I would hazard that it is better to imagine God badly than not at all. An error might bring a critical reaction, might provoke revisions, might become a stage on the road to excellence—whereas a lack of courage to try will lead to indifference. This leads me to the claim that rejecting the possibility of creating images is tantamount to rejecting the search for the image and likeness of God. It is a sin of indifference. Fear and narrow-mindedness are behind it. Rejection of the possibility of images is a sign of false humility and spiritual sloth; like any human vice, it can be translated into human weakness.”

Further on in his essay Grabowski explains how this willingness to proliferate images is typical of Roman Catholic dynamism, as opposed to say, Orthodoxy, which has much stricter canons of what count as acceptable representations of God and the saints. In this Grabowski approaches the position of the philosopher-theologian Jean-Luc Marion who argues in his The Crossing the Visible that Catholic kitsch is a safeguard against idolatry, because nobody would actually confuse it for God. There’s something to that!

As luck would have it, in between reading Przywara, I ran across the piece “Who’s Afraid of the Analogia Entis?” by Matthew Milliner. The author encourages his Protestant colleagues to open themselves to analogy. Their resistance was/is strong enough that the piece is part of at least an eight year old thread of posts advocating analogy for a Protestant audience. He even manages to enlist Jonathan Edwards on his side several times.

Matthew and I had a pleasant exchange. He pointed me to the lecture above. In it he argues the graybeard images of God the Father are heretical, because they are not sufficiently analogical. He takes an interesting turn toward the end by suggesting that American landscape painting (I must confess to a weakness against the Hudson School) might be more orthodox than the Orthodox (and Catholic) depictions of God the Father he critiques earlier in his lecture!

Yet, I wonder whether such representational purity is analogical or whether it falls into the dialectic (“Protestant,” if you will) trap of making God so transcendent that we are left with a brute world–no matter how nice the landscaping and lighting–without God.

The randomness on my facebook wall continued as Fr. Jonah Whiteford (an Orthodox priest) pointed out that depictions of God the Father as a graybeard were traditionally justified by identifying the Ancient of Days in Daniel 7:9 with God the Father:

“I beheld till the thrones were cast down, and the Ancient of Days did sit, whose garment was white as snow, and the hair of his head like the pure wool: his throne was like the fiery flame, and his wheels as burning fire.”

He even provided me with a florilegium of Patristic texts that make this very argument right here.

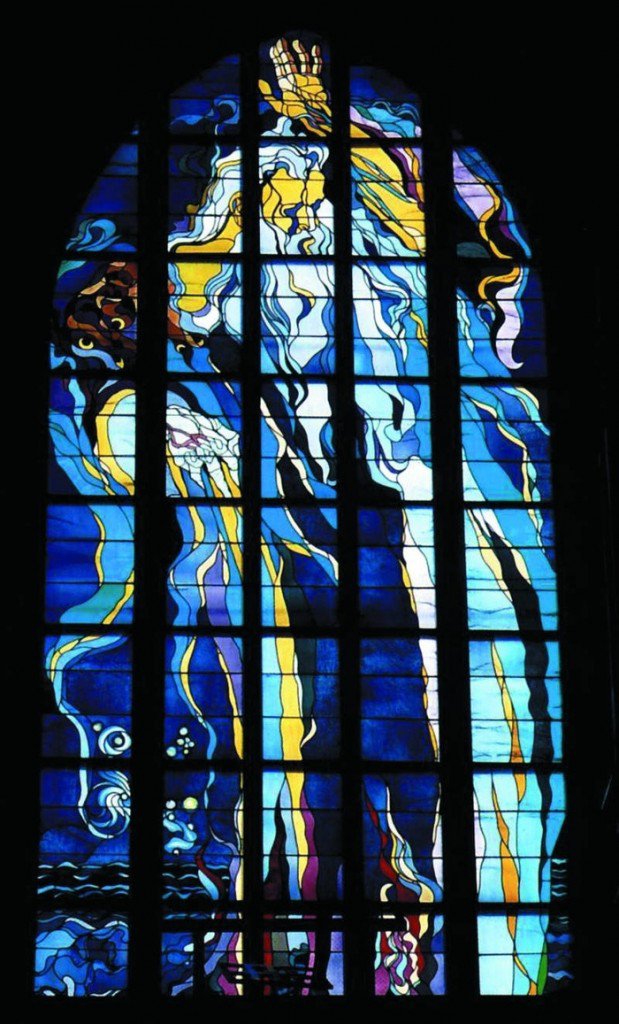

At this point, confused as I was, I realized that I had at least two potential justifications for the outstanding stained-glass window by Wyspianski in the Franciscan church in Krakow where Monika and I got married.

This magnificent figure is either a badly conceived yet brave (even if heretical) attempt at representing the Father (as all of them might equally be, even the absences of the landscapes…), or a representation that could potentially fit into some of the oldest canons of representation.

Wherever one might fall in this discussion, Przywara supplements Grabowski by reminding us that even if the image gets garbled in one telling, then the next telling will productively garble up the image in a new way as it corrects the previous one with new analogies:

“He is the one who lights up before us when we stand at a distance, and who lights up before us to urge us on. He is the infinite light that becomes ever more distant the closer we come to Him. Every finding is the beginning of a new searching.”

I’ve probably badly garbled up some points in this rambling account of recent discoveries, but you get the idea…

As Samuel Beckett once said, “All of old. Nothing else ever. Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”