There is nothing like the thrill of discovering a new vein of thought. The only thrill greater is the discovery of a new vein of thought in a thinker you thought you knew.

Alasdair MacIntyre is someone who is frequently quoted in theology and philosophy papers. You see his After Virtue referenced all over the place. You might also find mentions of his God, Philosophy, University and many tiresome variations on the title Whose Justice? Which Rationality?

You almost never hear about the work Dependent Rational Animals. I think we are all the worse for it. This is a remarkable book with an opening salvo as memorable as the one in After Virtue.

The topic of Dependent Rational Animals is human inter-dependence, with the emphasis on dependence. It is a topic I have broached many times, ror example, when talking about Kristeva’s appreciation of St. John Paul II and in the context of the extended family’s collapse.

MacIntyre talks approaches dependence from an interesting angle. He presents disability as a revelatory situation. It is revelatory because the extreme case, although MacIntyre argues the extreme case is actually more commonplace than we like to remember, reveals to us something that is the case for all of us:

We human beings are vulnerable to many kinds of affliction and most of us are at some time afflicted by serious ills. How we cope is only in small part up to us. It is most often to others that we owe our survival, let alone our flourishing, as we encounter bodily illness and injury, inadequate nutrition, mental defect and disturbance, and human aggression and neglect. This dependence on particular others for protection and sustenance is most obvious in early childhood and in old age. But between these first and last stages our lives are characteristically marked by longer or shorter periods of injury, illness or other disablement, and some among us are disabled for their entire lives.

These two related sets of facts, those concerning our vulnerabilities and afflictions and those concerning the extent of our dependence on particular others are so evidently of singular importance that it might seem that no account of the human condition whose authors hoped to achieve credibility could avoid giving them a central place. Yet the history of Western moral philosophy suggests otherwise. From Plato to Moore and since, there are usually, with some rare exceptions , only passing references to human vulnerability and affliction and to the connections between them and our dependence on others. Some of the facts of human limitation and of our consequent need of cooperation with others are more generally acknowledged, but for the most part only then to be put on one side.

And when the ill, the injured and the otherwise disabled are presented in the pages of moral philosophy books, it is almost always exclusively as possible subjects of benevolence by moral agents who are themselves presented as though they were continuously rational, healthy, and untroubled. So we are invited, when we think of disability, to think of “the disabled” as “them,” as other than “us,” as a separate class, not as ourselves as we have been, sometimes are now, and may well be in the future.

This passage also throws a new light upon the Walker Percy fragment we featured yesterday. The stigma attached to depression and other mental diseases make them that much more difficult to cope with. The irony is that these diseases lead to isolation, but the lack of acceptance and understanding associated with them only leads to more isolation. It is a vicious circle propagated by the cult of self-reliance and success. The unwillingness to acknowledge such problems misses a revelatory moment.

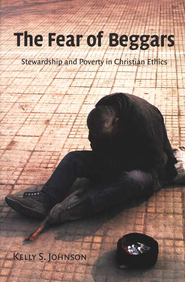

In the end I think this also is related to our fear of beggars. The beggar’s reliance upon our help is so overwhelming that one feels the need to ignore them in order not to see a humbling truth about oneself.

Luigi Giussani liked to say the beggar is the protagonist of history, rather than the autonomous individual destined for endless economic dynamism. To not understand the fact that dependence is a necessary condition of our lives, rather than a temporary condition, is to miss a great deal about what it means to be human–pretty much most of what it means to be human.

There is no greater witness to this than John Paul II during the last years of his pontificate.

The ridicule he endured in the media for his disabilities shows how difficult a truth this is to swallow, but swallow we will.