This is strange, since all the readings on the first Sunday of Lent hone in on the mystery of Original Sin. The Gospel reading takes the dramatic crown by recounting Christ’s temptation in the desert (breathlessly retold in one of the most famous modern literary episodes in The Brothers Karamazov–something I’d like to return to later).

So, I’m surprised, and a little bit disappointed, that my crack research doesn’t indicate that the first Sunday of Lent is officially called “Original Sin Sunday.”

Can I claim copyright on that?

I’ll concentrate upon the first reading from Genesis, which later became the backbone for the doctrine of Original Sin thanks to the prisms of St. Paul, the early Christians, Augustine, and pretty much the rest of the Western theological tradition after him. Just because the original authors, nor the Jewish theological tradition that emerged from them, doesn’t mean that it’s not there. It is a legitimate theological example of the Jews of the New Testament doing what Richard B. Hayes calls reading backwards, in order to see insights that weren’t originally apparent in the divine text. Or, to put it in the words of The Four Quartets:

I’ll concentrate upon the first reading from Genesis, which later became the backbone for the doctrine of Original Sin thanks to the prisms of St. Paul, the early Christians, Augustine, and pretty much the rest of the Western theological tradition after him. Just because the original authors, nor the Jewish theological tradition that emerged from them, doesn’t mean that it’s not there. It is a legitimate theological example of the Jews of the New Testament doing what Richard B. Hayes calls reading backwards, in order to see insights that weren’t originally apparent in the divine text. Or, to put it in the words of The Four Quartets:

We had the experience but missed the meaning.

And approach to the meaning restores the experience

In a different form.

I should add that even though Eastern Orthodoxies (there is no one single uniform “Eastern Orthodoxy”) don’t necessarily articulate Original Sin, that doesn’t mean, as argued by John Panteleimon Manousskis, that it doesn’t exist implicitly in the Eastern tradition(s).

The text from Genesis that was read on Original Sin Sunday is generally read as demonstrating the sin of pride, the original sin:

But the serpent said to the woman:

“You certainly will not die!

No, God knows well that the moment you eat of it

your eyes will be opened and you will be like gods

who know what is good and what is evil.”

The woman saw that the tree was good for food,

pleasing to the eyes, and desirable for gaining wisdom.

So she took some of its fruit and ate it;

and she also gave some to her husband, who was with her,

and he ate it . . .

The standard interpretation, at least in the Western Protestant world, would have us believe that the pride consists in grasping for divinity. On this reading humanity loses God by wanting to become gods.

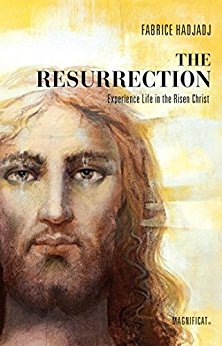

The French Catholic philosopher Fabrice Hadjadj, who is something like the second coming of Walker Percy, starts from this standard interpretation and quickly demolishes it in his The Resurrection: Experience Life in the Risen Christ. I make this comparison, because the self-help book sound of his book title, and his tongue-in-cheek approach using paradoxical examples culled from life in the ordinary, remind me of Percy’s Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book. Furthermore, I think the following makes Hadjadj’sThe Resurrection perfect Lent reading, but you be the judge:

The French Catholic philosopher Fabrice Hadjadj, who is something like the second coming of Walker Percy, starts from this standard interpretation and quickly demolishes it in his The Resurrection: Experience Life in the Risen Christ. I make this comparison, because the self-help book sound of his book title, and his tongue-in-cheek approach using paradoxical examples culled from life in the ordinary, remind me of Percy’s Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book. Furthermore, I think the following makes Hadjadj’sThe Resurrection perfect Lent reading, but you be the judge:

We would think that the worst possible thing would be “to make oneself out to be God,” whereas one psalm declares: You are gods, sons of the Most High, all of you (Ps 82:6). The danger is not to make oneself to be God, but to consider this name without the biblical key for understanding.

The following is the linchpin:

For is we take this name [you’re gods] according to the interpretation it gives, the real tragedy is instead that we do not make ourselves out sufficiently to be gods or messiahs, that is, sons of the Most High.

The statement above from Hadjadj seems to intentionally take a statement frequently attributed Leon Bloy–author of the influential fauvist novel The Woman Who Was Poor, and a major influence upon Hadjadj himself–up one notch . . .