The remarkable thing about Spike Jonze’s recent movie Her are the many questions it manages to raise and then completely ignore. Perhaps it would be incorrect to call these plot holes. It’s more like Jonze and the characters he has created are simply oblivious to the intellectual and ethical challenges the plot poses but fails to address.

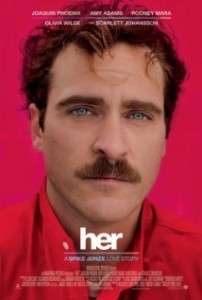

For those who haven’t seen it, the movie is set in the relatively near future and follows the story of Theodore (Joaquin Phoenix), a recently divorced ghostwriter in the employ of BeautifulHandwrittenLetters.com, and Samantha (voice of Scarlett Johansson), Theodore’s artificially intelligent, self-conscious computer operating system. Samantha has barely finished installing before she and Theodore find themselves falling for one another. The rest of the film proceeds in surprisingly typical rom-dramedy fashion with Samantha’s disembodiment filling in for the genre’s usual conflict-generating devices (ex-lovers, class divides, difficult in-laws, etcetera).

Among the many elephants Jonze leaves scattered about the room are all of the political and moral implications of purchasing an artificial “person” like Samantha. Isn’t there something quite wrong about purchasing a self-conscious entity to organize your email, take your messages, make your dinner reservations, and otherwise be limitlessly available to do your bidding? Isn’t there something even worse (if that’s possible) about becoming romantically—and yes, sexually—involved with that purchased entity?

These questions are not merely unaddressed by Theodore, they seem to be actually unavailable to him. His mental environment appears to be truly post-moral and emotivist, his political and ethical vocabulary thoroughly collapsed into the language of therapy. That is where the real action in the movie takes place: in Theodore and Samantha’s feelings. What should be troubling questions about the rights and responsibilities of persons natural and artificial are invisible, because they do not implicate anyone’s emotions. Theodore and Samantha apparently feel nothing in particular about her status as property, so they (and Jonze) can let the issue slide.

With some measure of trepidation, I posit that there is a nexus between this therapeutic totalism, the abolition of political and moral categories in favor of emotional ones, and Upper Middle Brow art (an emerging form which has been written about here before and of which Her is exemplary). Her represents something of a paradigm shift in that not only is the audience being flattered and its self-delight left undisturbed, this same courtesy is extended to the fictional characters. I will go one step further (out on the limb) and suggest that this confluence of ethical and artistic trends has something to do with disembodiment.

This is convenient for me as I write about Her, since embodiment or lack thereof happens to be one of the things that Theodore and Samantha do have feelings about. The fact that Samantha lacks a physical form is essentially the couple’s only relational hang-up. But in the context of the film, this absence turns out to be surprisingly insubstantial given the apparent obsolescence of the human body. All manual labor (so far as we see) has been replaced by technology, and even physical input devices for interacting with this technology, like our keyboards and touchscreens, have been largely eradicated in favor of voice commands. When it comes to what bodies are for, Theodore and Samantha apparently see little use for them aside from sexual contact.

Because they (and again, Jonze) are ultimately willing to treat fantasized, verbal sexual encounters (“phone sex”) as substantially equivalent to physical relations, disembodiment turns out to pose a real difficulty not for what it prevents but for what it enables. Their relationship hits the rocks when Theodore discovers that Samantha can and does carry on multiple conversations while she is communicating with him. In spite of her protestations to the contrary, he cannot escape the feeling that this prevents her from being fully present with him. Of course, we have no notion of what the subjective experience of an artificially hyperintelligent being might be like. From Samantha’s perspective, perhaps she is capable of carrying on thousands of conversations while being just as present in any one conversation as a human. But this violation of the human scale prevents her from satisfying one of Theodore’s relational demands: exclusive attention.

As Margaret Blume has argued (following Simone Weil), there is a connection between attention and embodiment. On the one hand, the demand for attention comes out of our embodiment, because our embodiment subjects us to the possibility of force and reduction to being a thing (that is, a body can become a corpse). On the other hand, the limits on our attention imposed by our embodiment may be independently significant.

The ability to enact multiple “intimacies” at one time is familiar to us digital natives. Through text messaging, G-chat, and a host of other communications platforms, we can be present in a variety of virtual forums simultaneously, all in addition to (and perhaps at the expense of) our physical presence. The reason some find this prospect troubling is the same reason that Theodore cannot get past his need for exclusive attention. Something would be lost with our bodies and the limits they impose.

What would be lost is the prospect of being wholly consumed, being exhausted, being used up, being revealed as finite and dependent. Our limits create the opportunity to experience an absolute investment of ourselves in some Other, whether the workman’s total absorption in his task, or the complete self-gift of the lover, or the mystic’s annihilation in contemplation of the divine. On the one hand, these are all occasions for transcendence, but on the other hand, it is in this very plumbing of the depths of our humanity that we discover we are not bottomless.

Our embodiment reminds us that we are creatures, things that might not have been and will someday pass away: from dust to dust. And our creaturely limits are foregrounded by our every encounter with external reality, of which mortality is only the most final. Only by avoiding the world, by shrinking the scope and depth of our activity, can we avoid being exhausted. We can only transcend our quantitative limits by submitting to qualitative ones. Thus, as Samantha’s processing power grows, she “upgrades” herself to a post-material, quantum computer, a purer intelligence, abandoning depth for limitless extent, trading the solid determinacy of a cube for the flat infinity of a mathematical plane.

In my final evaluation of this tortuous and possibly untenable string of associations, I think what we have in Her, particularly in its treatment of embodiment, is an unintentionally drawn blueprint of the Upper Middle Brow and its flattering treatment of its emotivist audience. In order to flatter an artificially reduced person, to “make consciousness safe” for him, to avoid disturbing his “fundamental view of [himself], or society, or the world,” your own narrative must become constrained in particular ways. In Her, we can see the bendings of the funhouse mirror, which are necessary to return a warped but flattering image of the viewer. And what is the manner of this constraint, what dimensions must be reduced, elided, and ignored: the moral, the political, and the physical.