The late Fred Phelps made his Westboro Baptist Church famous by being as outrageously offensive as possible. Perhaps the most universally reviled of Phelps’s many controversial tactics was the picketing of military funerals. Waving signs reading “THANK GOD FOR DEAD SOLDIERS,” Westboro disciples made not only a political statement but a theological one as well. According to Phelps, the deaths of American soldiers signified God’s judgment on a nation that had abandoned the Christian religion by tolerating homosexuals.

The vast majority of American Christians reject Phelps’s message of hate, but too many actually share one of his core beliefs. Many Christians believe that America’s political fortunes depend on the government’s attitude toward religion. For example, Joel Rosenberg’s book Implosion (reviewed in Fare Forward, Issue 2) argued that by adopting policies inconsistent with “biblical principles,” America has sown the seeds of its own destruction and will cease to be a world power unless it changes course.

Similar sentiments are widely shared on the Religious Right, and departures from traditional morality or “Judeo-Christian” religious observance are blamed for all kinds of evil. Examples of this logic are easy to find. In the wake of the Great Recession, many conservatives argued that the crisis could have been averted by a morality of individual responsibility. And though he subsequently walked back the comments, Mike Huckabee linked the Sandy Hook Elementary shootings with America’s ban on school prayer.

This tendency to find spiritual roots for national crises is not unique to America. In fact, the definitive work on the issue was written more than a millennium before America’s founding. At that time, Christianity was in a very different position. In the last days of the Roman Empire, St. Augustine wrote De Civitate Dei contra Paganos (The City of God Against the Pagans) to respond to charges that Rome’s abandonment of traditional religion for the new faith of Christianity was responsible for the decline in its power. Augustine’s argument draws valuable distinctions between different modes of “apocalyptic” thinking that remain relevant today.

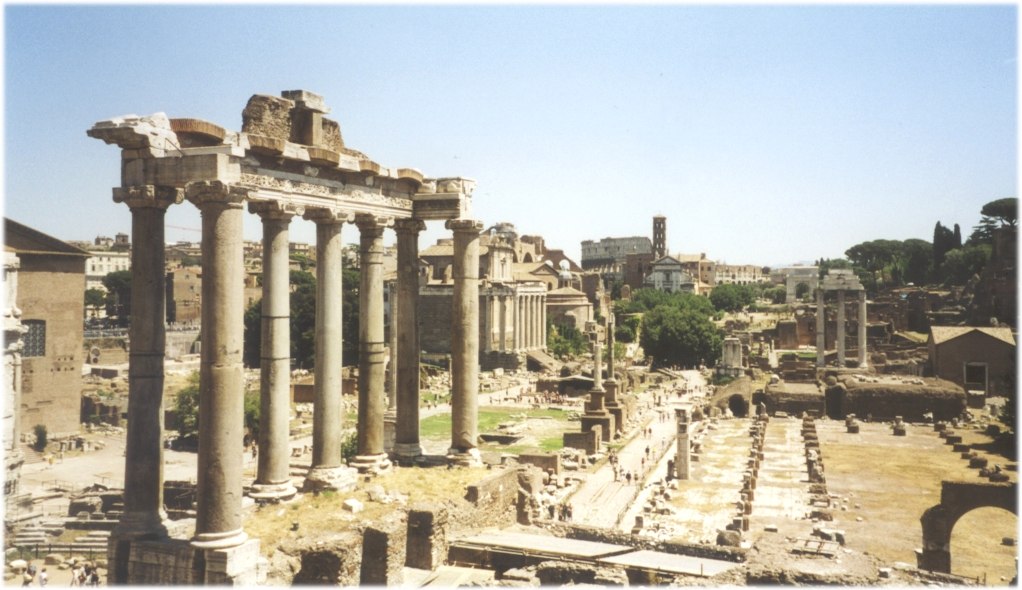

“Apocalypse” (from the Greek apokalypsis) literally means “un-covering” or “unveiling.” Many kinds of political discourse are “apocalyptic” in the sense that they look behind appearances to discern a nation’s future. The Romans practiced many forms of divination, like augury (the interpretation of events in the natural world) and haruspicy (the interpretation of the entrails of sacrificed animals), to make political predictions. But as their charges against Christianity reveal, they also saw religious practice as having political implication. In the same way, modern Americans often blame national troubles on departures from traditional religion or morality. Moreover, we frequently look to Rome for historical parallels with ourselves: Rome—the great city that brought peace to the world, but then collapsed under its own weight. Will we share its fate?

It is only natural for America to compare itself to Rome. America’s founders called their new state a “republic” after Rome’s res publica, and our constitution carries echoes of bygone Roman institutions. The men who shaped our early nation drew inspiration from the writings of Cicero and Polybius, and they combined elements of monarchy, oligarchy, and democracy in a single constitution, just as the Romans had done before them. They gave us a Senate because Rome had a Senate. They gave us an electoral college because the Romans voted in blocks. They gave our president veto power just like a Roman tribune.

Of course, the comparisons between the Roman and American empires do not end at the founding. The ways in which our government has evolved and the way we construe our role on the world stage reveal a continuous similarity between our two states. If we look at how Rome understood the disasters that befell it and how Augustine corrected that understanding in City of God, perhaps we can find common assumptions and transferrable insights for America’s own self-understanding.

Over the centuries, historians have posited many causes of Rome’s decline, usually with the aim of warning their own societies to avoid Rome’s fate. Perhaps low birth rates, epidemic disease, and economic instability played a part, but the Germanic barbarians delivered the final blow. The Western Empire finally collapsed in 476 A.D., when Romulus Augustus was deposed, but many historians claim that the turning point came almost 70 years earlier, when the German Goths sacked Rome in 410. The sack shocked many of the empire’s inhabitants because the city had not had a foreign army within its walls for 800 years. The Roman state had seemed like it would last forever. How could this have happened?

The most traditional of the Romans blamed Christianity for the disaster. Throughout the fourth century, Christians had become more numerous and more influential in the empire. Citizens who still adhered to Rome’s traditional polytheistic religion believed that if Rome had not recently abandoned its gods, then the gods would not have abandoned Rome to the barbarians. Augustine objected to the charges that the pagans made against the church.

But the pagans were not the only ones disturbed by Rome’s decline. Many Christians wondered what the destruction of Rome meant concerning the promises of God. Jerome bemoans the depredations of the barbarians in some of his letters. When he heard about the sack of Rome, he quoted Psalm 79: “O God, the heathen are come into thine inheritance; thy holy temple have they defiled; they have laid Jerusalem on heaps.” For Jerome and many others, Rome had become a Christian empire.

Almost a hundred years before the Goths entered the city of Rome, Constantine had won a devastating civil war in which he installed himself as the sole emperor. During the course of his conquest, he began to favor Christianity. The church historian Eusebius viewed the triumph of Constantine over his enemies as the triumph of Christianity over paganism. Eusebius portrayed Constantine as a second messiah who had ushered in a new heavenly age. Rome had been transformed. It was no longer a pagan empire; Rome had begun to establish the kingdom of God on earth.

The emperors after Constantine were not all devout and included one apostate, but the fourth century saw a steady Christianization of Rome’s political structures. Under Theodosius I, pagan religion was restricted, and Christianity became the state religion of the empire. Theodosius’s rule was the high point of Christian influence over the state, but less than twenty years later the Christian empire was at risk as the Goths swarmed Italy.

Augustine tackles two issues in City of God. First, he answers the pagan attacks on Christianity, which blamed the sack of Rome on the abandonment of pagan religion. Second, he defends the truth of the Christian faith and reassures believers that barbarian swords cannot destroy God’s promises—and he does all this in just 22 books.

According to Augustine, it was hypocritical for the pagans to blame the calamity on Christianity, because the sack of Rome was hardly the first tragedy to befall Rome. He catalogs devastating wars and natural disasters that took place before the advent of Christ, and he asks why the traditional gods did not save the Romans from those. Clearly, the pagan religion provided no better protection for the Roman state.

But Augustine’s more important corrective is directed at apocalyptic thinking among the Christians. Augustine argues that Christians must have a different vision of the New Jerusalem than that proposed by Eusebius. The Roman Empire might have had many Christians living in it, but that did not mean that it was a Christian Empire. Augustine contrasts two cities: the City of Man, which represents temporal government and includes the Roman state, and the City of God, which is the invisible Christian society that binds together all believers from every time and place. This City of God is the universal church.

According to Augustine, Christians have a dual citizenship. Our primary allegiance is to Christ and his city, but this allegiance does not necessarily conflict with our duties to the earthly city. The pagans believed that Christianity undermined the values that made Rome strong, but Augustine claims that Christian virtue allows believers to better fulfill their civic responsibilities. Christians act from a spirit of charity that seeks the best for others, while even the best Romans acted out of self-love. Christians will make better earthly citizens, but that doesn’t mean that they can transform the earthly city into the City of God.

Augustine shows that only one City of God exists, and it exists eternally. Earthly cities come and go. Augustine hopes that his readers will not despair when disaster strikes the City of Man because their Eternal City is unassailable. No one can thwart God’s purposes for his church. Rome, like all earthly cities, will pass away, so its temporal disasters should not cripple the Christian’s heart.

City of God has proved to be a timeless work because the corrective that Augustine gives seems to need reapplication to each generation. The centuries that separate us from Augustine are filled with people who have attempted to bring about the New Jerusalem through political schemes. We are merely the latest in a long line of Christians who have attempted to ensure material and political blessing through behavior modification. Isn’t that the mistake of the Pharisees, thinking that the promises of God belong to an earthly kingdom?

Augustine shows us the wrongness of apocalyptic thinking that puts eternal things in the service of temporal ends. This is easy to see in extreme cases like that Fred Phelps and the Westboro Baptists, but it is true regardless of degree: God is not a resource to be exploited for worldly politics. In contrast, the right kind of apocalyptic thinking should put the temporal things in eternal perspective. City of God reminds American Christians that their country is not the Christian nation; it’s just another earthly city in the process, long or short, of passing away. Augustine reassures us that even when America falls, God’s church will prevail. In the meantime, Christians should not withdraw from the earthly city. Augustine would ask you to take your dual citizenship seriously and work for the good of others through love.