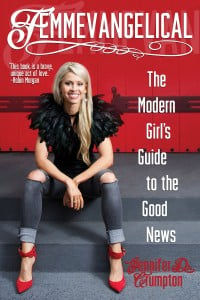

Here’s another excerpt from Femmevangelical: The Modern Girl’s Guide to the Good News.

This is from the chapter titled “‘In the Beginning’ Gets a New Ending”, which breaks down biblical literalism, describes how the New Testament was canonized, brings forward buried texts, and explores the history and purpose of mythos and logos.

Burying the Dead, Resurrecting Our Lives

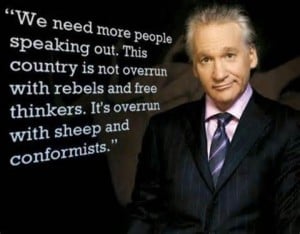

In light of this, I thought back to the Christian devotional books for women I read as a teenager. Stories not meant as modern morality tales were twisted into terrible recommendations of “holy behavior” for Christian women, teaching disempowering ideas I have long carried with me.

I once taught a Bible study for women at a church in Manhattan using the suggested book Esther: A Woman of Strength and Dignity by Charles Swindoll. Women are exhorted to be cunning and selfless like Queen Esther, who saved the Jews by daring to approach the Persian king un-summoned and request his favor, which could warrant death.” Swindoll draws bizarre and dehumanizing conclusions for modern women without acknowledging the reality of the story.

Scholars consider the book of Esther fictional; it is full of historical inaccuracies and is written in telltale early Jewish novella style. In true Hebrew Bible form, it is purposefully written as myth, using ancient oral tradition and shifting details to communicate a larger idea about the precarious history of Israel and the Jews’ sense of destiny. The character Esther was a Jew in exile in the Persian Empire around the mid-400s b.c.e., when she was kidnapped into a harem of King Ahasuerus, believed to reference Xerxes I. Hundreds of girl-children were “sent in” to the king (otherwise known as raped). Even if he never called for the girls again, they were confined within the palace walls for the rest of their lives as concubines, never to have lives or families of their own.

The character Ahasuerus makes Esther queen, the position being vacant because the previous Queen Vashti refused to obey his abusive orders. Her breaking point occurred when he summoned her to his drunken buddies’ boys’ night to “show off her beauty.” Ahasuerus punished Vashti for giving all the other women in the land the idea that they could question and resist their husbands’ commands. Even as queen, a woman with the audacity to stand up for herself was cursed and vanquished for her ungodly resistance to authority. This was the denigrating position young Esther was chosen to fill, but Swindoll does not talk about any of that.

What disturbs me about the traditional Christian interpretation of this story is that we are told with pride and awe that God purposefully inserted Esther into this hell hole to do God’s bidding and bring about God’s will. Why would an omnipotent God need to let hundreds of young girls get kidnapped and raped so that one of them could be put in position to beg for the lives of the Jews? The idea that God knowingly places women in abusive and dehumanizing positions to carry out a plan is gravely irresponsible—I’d call it evil.

In Swindoll’s devotional, in a chapter horrifyingly titled “There She Goes—Miss Persia!” Swindoll makes it sound festive and triumphant, like a musical starring Reese Witherspoon from Legally Blonde. He describes the period right after Esther is kidnapped and marinated like meat in beauty treatments for a year “under the regulations for the women,” exclaiming: “Look at that! It took an entire year for them to prepare these women to be presented to the king. That’s a lot of Oil of Olay and Lancôme, ladies and gents!” Really? He goes on to assume what Esther’s experience was like:

The original [biblical] text is colorful, [saying Esther is] “beautiful in form and lovely to look at.” Before long she will hear, “There she goes—Miss Persia,” And she will win the lonely king’s heart. It will be the classic example of the old proverb, “He pursued her until she captured him.” But at this point, she knows nothing about palace politics or a lonely king or what the future holds for her. She is simply living out the rather uneventful days of her young life, having not the slightest inkling that she will one day be crowned the most beautiful woman in the kingdom as well as the new queen of the Persian kingdom. My, how God works!

My, indeed. Xerxes was no poor, unassuming, lonely king; but Swindoll tries to make that excuse for his misuse of power more than once. The fact he thought Esther was the hottest of all the little girls is revolting, not something for Esther to be proud of, or for modern girls to aspire to. And we have no idea what Esther felt, since a male narrator tells her story.

Swindoll asserts these disturbing lessons: “God’s plans are not hindered when the events of this world are carnal or secular” (young girls getting raped and the queen enduring abuse: anything for “God’s plans”); “God’s purposes are not frustrated by moral or marital failures” (referring to Ahasuerus’ frat boy behavior and divorce of Vashti, which wasn’t a marital failure—that was misogyny); and “God’s people are not excluded from high places because of handicap or hardship”14 (referencing that Esther was an orphan and God used her anyway—getting kidnapped, raped, and held captive was not a hardship, but a compliment to women and a life-long spa day, in Swindoll’s interpretation).

Swindoll asserts these disturbing lessons: “God’s plans are not hindered when the events of this world are carnal or secular” (young girls getting raped and the queen enduring abuse: anything for “God’s plans”); “God’s purposes are not frustrated by moral or marital failures” (referring to Ahasuerus’ frat boy behavior and divorce of Vashti, which wasn’t a marital failure—that was misogyny); and “God’s people are not excluded from high places because of handicap or hardship”14 (referencing that Esther was an orphan and God used her anyway—getting kidnapped, raped, and held captive was not a hardship, but a compliment to women and a life-long spa day, in Swindoll’s interpretation).

While reading Swindoll’s book, I recalled a trauma I had repressed from the age of sixteen. Alone in a dance studio with my older male ballet instructor, he molested me. I thought at the time that if it was his desire, there seemed nothing for me to say or do about it. He brazenly assumed some sort of right to my body that I could not explain, and I had not been taught the critical thinking or sense of agency to stand up to him. Exposing him so he would not harm another girl would have never occurred to me.

To get through my guilt and shame over his actions—a typical irony of the abusive power dynamic—I turned to the only other thing as deeply ingrained in my Christian-girl consciousness as male supremacy: the fairytale interpretations of biblical womanhood that ignore atrocities. I avoided the confusion, pain, and humiliation by imagining this man—who had a wife and baby waiting to be brought to the U.S. from a small, poor Eastern European town—would turn out to be a prince, transforming me into a princess with a happily-ever-after ending. I never told a soul. It took me almost twenty years to realize it was a crime, because, in the Bible I was raised on, it wasn’t.

This Bible study of Esther marked the first time I questioned what a male authority figure was telling me the Bible meant. Swindoll (the author) was a senior pastor of a prominent church and chancellor of Dallas Theological Seminary, and because of his authority and influence, has now misdirected countless young women. People like to make Esther’s story romantic and fateful, but in the social reality behind this myth, about which the Bible is quite matter of fact, she was a subjugated pawn in the male political drama. She is rightly hailed a heroine, but she is not meant to be emulated, no questions asked, for millennia to come. Bringing Esther forward in a way that panders to makeup, beauty, and pageants forsakes the opportunity to talk about what women actually care about: making the world safer and more supportive for the true needs of girls and women: education, economic opportunity, the ownership of our own bodies.

Texts can open honest discussion of the inhumane conditions endured by women around the world. Instead of recreating Esther’s womanhood, feminists of faith should ask, What would the character Esther want us to do with her myth today to raise up women? Who are the Ahasuerus’ and his minions of today, and how do we overthrow them?

True wisdom, my friend Rev. Galen Guengerich once reminded me, is not for the faint of heart. Wisdom is creating a new definition of “biblical authority”—exploring our history and bringing it forward with the gospel of Jesus: freedom for the prisoners, release of the captives, sight for the blind, and God’s new reality that puts us in our rightful places. We are meant to do something about it.

Get Femmevangelical: The Modern Girl’s Guide to the Good News at Chalice Press, Amazon.com, or Barnes & Noble.