The movie mogul Sam Goldwyn once said, “If you want to send a message, use Western Union.”

Reading between the lines here he seems to be complaining about people using movies to preach politics, or whatever. Just goes to show that you don’t need to be a preacher to be preachy.

Last episode I preached on the evils of didacticism in fiction. But does that mean we should settle for entertaining our readers and leave their edification to the experts? I don’t think so, not just because that would drain our stories of significance, but also because you can’t truly get away from sending messages with your storytelling.

The Star Wars franchise is almost a cult, some people actually take all that Jedi stuff seriously and try to live like Like Skywalker or Obi Wan Kenobi. Why? For one thing people identify with them, and they find meaning in their stories, meanings that help them live their own lives.

Last time I said that the characters we write about should be free to be themselves, to have purposes of their own. They shouldn’t be one-sided signs that simply point to other things. They need to live. But that doesn’t mean they don’t point to other things anyway.

Analogical Storytelling

I’m not attempting to provide a technical definition here, merely one that helps me make a distinction. Here’s the distinction. An allegory is a story that exists solely to make a point. There is no space at all between the characters and what they represent. In analogical storytelling though, there is a measure of space between characters and their stories and the meanings they reflect. But there is still a connection. The space can be so broad only a literary critic can bridge the gap. The connection may not even be something that an author is aware he is making. Nonetheless, the connection is there.

The key thing here is there must be some sort of referent that exists apart from the the character’s awareness in the story, or even from the plot. And a reader may or may not detect it consciously. But its influence is still felt somehow.

What follows is not supposed to be exhaustive. These are merely ways this can work in my experience.

Autobiographical

I believe that every work of fiction is in some sense autobiographical. It takes a lot of work to tell a long story. To keep with it you need the obsessive energy that only personal experience provides.

The experience can be something in your childhood, or maybe its found in your personal longings. These things may not be easily detected in your stories, even by people who know you well. (With more thoughtful authors they can be so filtered and mutated that they may not even be seen by the author himself.) But they’re there–in the motives of the protagonist, in the obstacles he or she faces, in the plot that the story advances–there is some reference to the author. And because these things are meaningful to the author, the story may be meaningful to the reader.

Typological

Readers of the Bible should know what I’m referring to here. The Apostle Paul tells his readers that the scriptures are full of “types”.

King David is a type of Christ; Jesus said that even Jonah was a type. So, to this way of thinking, in some sense David and Jonah are like Jesus.

Obviously they’re unlike him too. The wonder of typology is that the differences can be as instructive as the similarities. David was an adulterer and a murderer and Jonah didn’t want to do what the Lord told him to do. That’s why they’re so interesting. These people are not just characters in an allegory, they have lives of their own. They make mistakes, they do stupid things. We can like them, or hate them, and still be able see that they point to things bigger than themselves.

As far as I can see, there are two ways to do this. The first can be seen in the biblical tradition, where things in a story can either refer backwards or forwards to things in a larger story. This is what makes history important, either a history that exists solely in literature, or much more audaciously, the one we all actually live in–history itself.

I think this appeals to the more sophisticated sort of Protestant minister. It gets you beyond the crude one for one representations of allegory while keeping you out of the mirky depths of mysticism.

But I’m afraid it won’t do. The Bible is full of references to heavenly things that by their natures actually take you outside of history. Just one example: Hebrews chapter 9. There we see that the temple in Jerusalem was a miniature copy of something that truly exists eternally in heaven.

Another approach, one that dips the toe into mysticism, but refuses to take the plunge, is depth-psychology. I think that’s what you have with Joseph Campbell and his analysis of mythology, especially his insightful hero’s journey. According to Campbell, something unconscious and universal is at work when we tell stories. That’s why certain themes and tropes keep reappearing no matter where you look. (I think this is also what we see in Christopher Booker’s, Nine Basic Plots). It is uncanny, I fell right into the hero’s journey structure in my own writing without giving it a thought. But is this just psychology and nothing more?

Again, this doesn’t seem to do. Depth psychology doesn’t go deep enough. Why should things work this way? Are all referents merely internal, as this seems to suppose? Or is the structure we find in ourselves in some sense a reflection of a larger structure that lends us meaning? And if that’s the case, where does that larger structure reside?

Metaphysical

Say “metaphysics” and for some reason people feel like you’ve lost your mind. That’s for mushroom-munchers and monks. You’d never know that most Christians believed in metaphysics for over a thousand years, or that the Inklings all did too.

Say “metaphysics” and for some reason people feel like you’ve lost your mind. That’s for mushroom-munchers and monks. You’d never know that most Christians believed in metaphysics for over a thousand years, or that the Inklings all did too.

Basically the metaphysical approach presupposes a meaningful world, meanings here being things that exist apart from us and and even apart from our awareness. We derive meaning from these larger meanings by participating in them. And the way that is done in fiction, at least if you want it to happen intentionally, is by using things in ways that are consistent with their intrinsic meanings.

The reader doesn’t need to know what you’re doing to benefit from it. I think the best contemporary example of this is The Chronicles of Narnia.

For the longest time people thought that C. S. Lewis had written a straight allegory with some weird incongruent stuff thrown in. It worked for him because, after all, he was an Oxford don and a great stylist. And while there is some allegory at work there, it is a little loose.

But it turns out, to everyone’s amazement, that the allegory may have been put there by Lewis to keep us from seeing what he was really up to. It appears that he even kept his good friend Tolkien in the dark about it. (Maybe he knew Tollers would be even more disapproving than he was!)

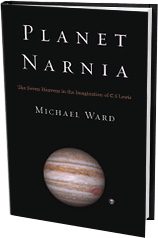

Michael Ward’s Planet Narnia has conclusively, I think, shown us that Lewis wrote each of the Chronicles with a planet from medieval cosmology in mind. He wanted the tone of each planet to not only shape the stories, but shape the perceptions of his readers as they read the stories. Each of the 7 stories is filled with symbols traditionally associated with each of the 7 planets. And I must confess–it works. It does for me anyway.

Now here’s another confession: I am up to this sort of thing in my writing. I don’t mean the planet stuff, specifically, just metaphysics generally. But I don’t draw attention to it, I just do it.

It’s not the only thing that informs my writing. But it is very important for me. But there is something else, something that qualifies even this. And that’s what I’ll get to next time.