Most of us have heard the phrase “Necessity is the mother of invention” so often that we never stop to question it. On a gut level, the narrative it creates in our mind seems undeniably true: Someone encounters a problem or need, so he or she devises a clever means by which to solve that problem or meet that need. Register the patent, cue the applause and let the money-printing begin. There’s just one problem with this story: It almost never happens.

In fact, if you read Jared Diamond’s excellent book Guns, Germs, and Steel, he argues that throughout human history invention virtually always precedes necessity. Alfred North Whitehead agrees, arguing that, “the basis of invention is science, and science is almost wholly the outgrowth of pleasurable intellectual curiosity… ‘Necessity is the mother of futile dodges’ is much nearer the truth.”

A case in point: The airplane. Orville and Wilbur Wright didn’t begin their glider experiments by polling Americans to see what their greatest felt need was in relation to travel. Neither did they consult the military to determine what generals were looking for in the next generation of cutting age weapons. Instead, they were driven by intellectual curiosity and, no doubt, personal ambition to be the first to solve the vexing problem of heavier-than-air flight. Not to mention the possibility of profit if their invention proved a success. The point is, no one came to the Wright brothers and said, “We need to fly.” Only once people saw the planes in action did the need to get one of their own kick in.

A case in point: The airplane. Orville and Wilbur Wright didn’t begin their glider experiments by polling Americans to see what their greatest felt need was in relation to travel. Neither did they consult the military to determine what generals were looking for in the next generation of cutting age weapons. Instead, they were driven by intellectual curiosity and, no doubt, personal ambition to be the first to solve the vexing problem of heavier-than-air flight. Not to mention the possibility of profit if their invention proved a success. The point is, no one came to the Wright brothers and said, “We need to fly.” Only once people saw the planes in action did the need to get one of their own kick in.

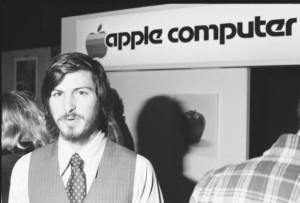

Another example: Steve Jobs. He didn’t transform Apple into the most profitable company in the world by asking people what they wanted and then giving it to them. He hated market research and focus groups, saying, “a lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.” So rather than pander to the public, Jobs and his team focused on setting nearly impossible goals for themselves and seeing if they could pull them off. There’s no question that the desire for profit was always lurking in the background, but Jobs was exceptional in his seeming indifference to money. He was more intent on creating disruptive technologies and then watching the world reshape itself in their image. A living embodiment of the Field of Dreams adage, “Build it, and they will come.”

Another example: Steve Jobs. He didn’t transform Apple into the most profitable company in the world by asking people what they wanted and then giving it to them. He hated market research and focus groups, saying, “a lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.” So rather than pander to the public, Jobs and his team focused on setting nearly impossible goals for themselves and seeing if they could pull them off. There’s no question that the desire for profit was always lurking in the background, but Jobs was exceptional in his seeming indifference to money. He was more intent on creating disruptive technologies and then watching the world reshape itself in their image. A living embodiment of the Field of Dreams adage, “Build it, and they will come.”

Read the biography of any great inventor, innovator or discoverer throughout history–Da Vinci, Franklin, Edison, Bell, Einstein, Tesla, etc.–and you’ll see the same story repeat itself. Intellectual curiosity leads to experimentation, which leads to invention, which leads to a piece of technology that people had never imagined before but which they can no longer live without. The only needs these inventors sought to satisfy were their own.

And rarely is the inventor the one who figures out how to profit from his or her creation–Steve Jobs and Thomas Edison being rare exceptions. Oftentimes, the inventor is left in the dust while other people profit by adapting the invention to their purposes. Speaking of which, it was Steve Wozniak who was the real creative genius during the early days of Apple. Jobs was just the salesman. If it were up to Wozniak, he would still be giving his inventions away for free. He didn’t have time to build a business around his inventions, because by the time he was finished with one, he was already onto the next, driven not by greed or ambition but the thrill of discovery.

And rarely is the inventor the one who figures out how to profit from his or her creation–Steve Jobs and Thomas Edison being rare exceptions. Oftentimes, the inventor is left in the dust while other people profit by adapting the invention to their purposes. Speaking of which, it was Steve Wozniak who was the real creative genius during the early days of Apple. Jobs was just the salesman. If it were up to Wozniak, he would still be giving his inventions away for free. He didn’t have time to build a business around his inventions, because by the time he was finished with one, he was already onto the next, driven not by greed or ambition but the thrill of discovery.

What does this have to do with Hollywood? Simple. Right now Hollywood is in bondage to “necessity is the mother of invention” thinking. At every stage of the filmmaking process, from development to distribution, studios are driven solely by the desire to discern the needs of an ever-fickle public and then meet those needs through a slate of films. That’s why virtually every big budget movie released these days is a sequel, remake or adaptation of a pre-existing work. Public buy-in has already been established, supposedly exposing people’s deep desire for more of the same. So that’s exactly what Hollywood gives them–more of the same. Sort of. Even then, the marketing execs continue to tinker with the film from script to release, bringing in focus groups, additional writers, and shooting multiple endings to see which one scores the highest with test audiences. Every precaution is taken to avert failure. There’s just one problem with this model: it fails miserably 99.9% of the time.

What does this have to do with Hollywood? Simple. Right now Hollywood is in bondage to “necessity is the mother of invention” thinking. At every stage of the filmmaking process, from development to distribution, studios are driven solely by the desire to discern the needs of an ever-fickle public and then meet those needs through a slate of films. That’s why virtually every big budget movie released these days is a sequel, remake or adaptation of a pre-existing work. Public buy-in has already been established, supposedly exposing people’s deep desire for more of the same. So that’s exactly what Hollywood gives them–more of the same. Sort of. Even then, the marketing execs continue to tinker with the film from script to release, bringing in focus groups, additional writers, and shooting multiple endings to see which one scores the highest with test audiences. Every precaution is taken to avert failure. There’s just one problem with this model: it fails miserably 99.9% of the time.

That’s not to say Hollywood studios don’t make money. They make scads of money–even thought their balance books seldom show it. But they rarely come close to creating art. And in my opinion, making money should be the last thing on a filmmaker’s mind. Like Steve Jobs, filmmakers should be focused instead on ushering their dreams into existence, creating “disruptive technologies” that reshape the world in their image. Unfortunately, for any artist seeking to work in Hollywood, the system keeps pushing money and profit to the forefront. The result is a steady stream of films that are severely lacking in beauty, originality, honesty, vision, bravery, depth–virtually anything we might equate with great art.

Why do people keep paying good money to see these films? I can’t say for sure, but I’m reminded of a line from a poem written by my college friend Theresa Forsyth: “He said the devil pissed in a bottle, and the whole damn town, the whole damn town ran and drank it.”

Maybe that’s too cynical. Perhaps, like me, they remember being profoundly affected by film at one time, and they continually hold out hope it will happen again. But I think it’s more likely that we so rarely encounter good art these days that our tastes have been largely denuded and destroyed. Like someone who eats nothing but junk food, we simply don’t know enough to desire anything better. And with Hollywood delivering a steady diet of sugar, salt and fat, the drift toward the path of least resistance becomes increasingly difficult to resist.

And yet, every once in a while a miracle occurs, and a truly great work of art makes it to the screen. Not only that, the film is embraced by the public, showing that a flicker of desire for beauty, truth and wonder still exists. More often than not, this rarity is an independent film (a film made outside of the studio system) or a foreign film, leading many people to erroneously assume that foreign and indie films are by definition superior to Hollywood fare. Try telling that to a curator of a major festival, such as Sundance, Toronto or Cannes, who has to wade through literally thousands of crappy indie and foreign films each year searching–hoping–for a few gems in the pile. By and large, most indie and foreign films are just as bad as most studio films, because they are produced according to the same misguided process by filmmakers who are merely trying to create a stepping stone into the big leagues. The only reason we think they’re better is that, by and large, we only get to see the rare exceptions, those films what only exist because the artist was obsessed with making his or her vision a reality, and somehow the stars aligned in such a way to make the singularity occur.

And yet, every once in a while a miracle occurs, and a truly great work of art makes it to the screen. Not only that, the film is embraced by the public, showing that a flicker of desire for beauty, truth and wonder still exists. More often than not, this rarity is an independent film (a film made outside of the studio system) or a foreign film, leading many people to erroneously assume that foreign and indie films are by definition superior to Hollywood fare. Try telling that to a curator of a major festival, such as Sundance, Toronto or Cannes, who has to wade through literally thousands of crappy indie and foreign films each year searching–hoping–for a few gems in the pile. By and large, most indie and foreign films are just as bad as most studio films, because they are produced according to the same misguided process by filmmakers who are merely trying to create a stepping stone into the big leagues. The only reason we think they’re better is that, by and large, we only get to see the rare exceptions, those films what only exist because the artist was obsessed with making his or her vision a reality, and somehow the stars aligned in such a way to make the singularity occur.

When people flock to these rare indie/foreign gems in droves, the studios tend to offer the creative teams behind them an opportunity to produce their next project within the Hollywood system, hoping to replicate the success of their first film. But this almost never works, because the minute an artist enters the Hollywood system, he or she is now beholden to all sorts of pressures and requirements that didn’t exist during the making of his or her first film. Instead of taking the time and money required to fulfill an artistic vision, they find themselves on a treadmill designed to churn out product in order to generate profit. And no true artist can survive in that system for long.

There are a few notable exceptions–such as Joel and Ethan Coen, Woody Allen, Wes Anderson, P. T. Anderson, Quentin Tarantino and Darren Aronofsky–artists who work within the Hollywood system and yet somehow manage to consistently create films of lasting social significance. I’m not sure how to explain these anomalies except to say that most of them got their start during a time when Hollywood was far less risk averse than it is today. Somehow or other, they have found champions within the system, perhaps by scoring just high enough on the commercial success or critical acclaim scale to retain their membership in the club. And the studios are willing to gamble that, given enough time, they will do it again. But even these exceptions have to work within stringent parameters in terms of budget. No one would dare hand them the keys to the kingdom.

There are a few notable exceptions–such as Joel and Ethan Coen, Woody Allen, Wes Anderson, P. T. Anderson, Quentin Tarantino and Darren Aronofsky–artists who work within the Hollywood system and yet somehow manage to consistently create films of lasting social significance. I’m not sure how to explain these anomalies except to say that most of them got their start during a time when Hollywood was far less risk averse than it is today. Somehow or other, they have found champions within the system, perhaps by scoring just high enough on the commercial success or critical acclaim scale to retain their membership in the club. And the studios are willing to gamble that, given enough time, they will do it again. But even these exceptions have to work within stringent parameters in terms of budget. No one would dare hand them the keys to the kingdom.

You might think I’m being too hard on the studio system. After all, hasn’t the desire for profit always been the driving force of Hollywood? And the conflict between art and profit surely predates the film industry by centuries, with even Samuel Johnson admitting, “No man but a blockhead ever wrote except for money.” So perhaps I’m criticizing the studio system for failing to nail a target it never intended to hit. After all, this isn’t art, it’s just entertainment.

If entertainment is all you want, I suppose that answer will suffice. But for those of us who dream of something more, who remember a time when movies offered something more, that answer just isn’t good enough.

What will it take to change this situation? It’s tempting to blame the audience. If people would simply vote with their pocketbook, Hollywood would change. But I don’t think that’s fair. As Steve Jobs said, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them. The same goes for the studios, themselves. So if anything’s going to change, it’ll have to be the artists who lead the way.

Until then, driven by necessity, Hollywood will continue to produce futile dodges instead of disruptive technologies. And those of us who regard ourselves as artists will have no one but ourselves to blame.