Two articles about Chinese Christianity were recently published in the Journal of Global Christianity.

“Conversions to Christianity Among Highly Educated Chinese” (by Niek Tramper)

Here is the article’s abstract:

Chinese churches both in mainland China and in other parts of the world have demonstrated remarkable spiritual and numerical growth during the last three decades. Chinese intellectuals, in particular, show an interest in Christianity.

This study highlights a variety of reasons for this. Christianity is seen as an important source for renewing values and ethics in order to build up society beyond communism and materialism. Other factors instrumental in the conversion of Chinese intellectuals to Christian faith include the unconditional love and forgiving attitude of Christian friends, the experience of miraculous healing or recovery, as well as the life-changing power of the Gospel encountered in the life of the church.

However, young Chinese intellectuals who have become Christians abroad and return to China often experience a reverse culture shock and return to their previous convictions. This study explores main factors in conversions and in later relapses among highly educated Chinese. It underlines the need for a loving Christian community welcoming foreign students, researchers, and businesspeople. It also shows the need to prepare those who return to their country for reverse culture shock.

Niek Tramper begins by asking the question, “What prevailing factors in the past ten years have caused the transition of highly educated Chinese from a lifestyle marked by all kinds of non-Christian beliefs to Christian faith and membership in a Christian church?” I think he gives a good survey of various factors influencing highly educated Chinese.

On the other hand, I’m glad Tramper tempers his remarks when he writes, “A growing number of reports indicate a reverse movement: Chinese intellectuals turning back from their earlier conversion, or Christians who leave their conviction for agnosticism, atheism, or another religion.”

Some of the factors include the inability to connect to a church, the pressure of doing business, opposition by family, and “reverse culture shock” (for those who become Christians while outside China but who eventually return home).

“Christ Against Culture? A Re-Evaluation Of Wang Mingdao’s Popular Theology” (by Andrew Song)

Here is the abstract:

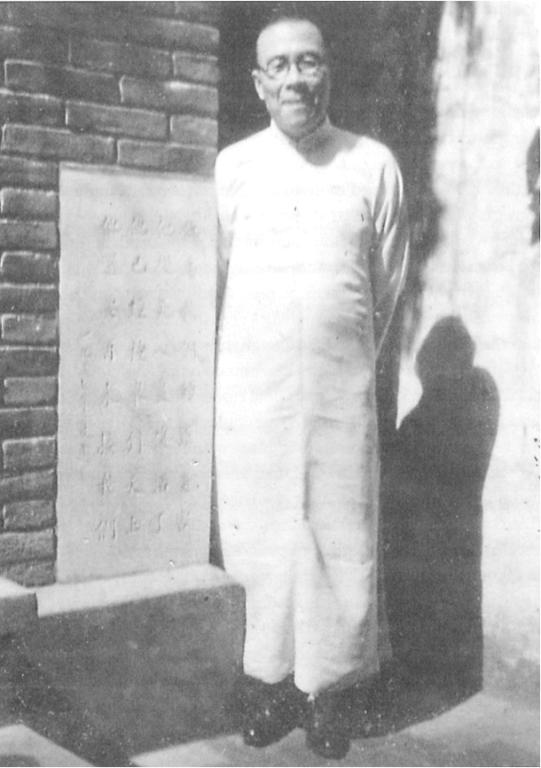

Since its publication, H. Richard Niebuhr’s (1894–1962) divisions in his Christ and Culture (1951) were used as a standard for categorizing someone’s view on cultural engagement. In the past sixty years, scholars applied Niebuhr’s “Christ and Culture in Paradox” or “Christ against Culture” to Wang Mingdao’s (1900–1992) theology.

Almost twenty-five years after Wang’s death, this paper re-evaluates Wang’s popular theology and his view on how the church should love her neighbour. By relocating Wang and his theology in their historical and theological contexts, this paper argues that Wang’s approach to the church’s cultural mandate is a priori. For Wang, since individual persons compose the society and are the players of certain cultures, then the goal of changing the society and reforming the culture can only be achieved by changing people’s hearts, which is the work of the Holy Spirit through the gospel. The relationship between individual conversion and social reform is not sequential; rather, the former enables the latter.

Andrew Song provides a helpful overview of Wang Mingdao, a significant figure within Chinese church history. He does well to situate Wang’s life in context.

Wang preached that the church should focus on individual conversion rather than social reform, allowing the latter to be a fruit of the former.

This background explains in part why many contemporary Chinese Christians believe the church should not be involved in social activism; on the other hand, readers must keep in mind the specific cultural context in which Wang lived. Given the Fundamentalist-Liberal debates of his day, conservatives saw anything that anything that sounded like “social ministry” as code for anti-evangelism and theological compromise.

Nowadays, however, many Christians around the world seek to reform corrupted elements of society without lacking fervor for evangelism and the church. Emphasizing separation of church and state, “Wang understood that the way for the church to ‘engage the culture’ is to love her neighbors, based on her own love for God.” Admirably, Wang prioritized the church over citizenship, yet I’m left with two thoughts.

First, I suspect his counsel is less applicable today and would only spur churches to lose balance by re-adopting a strong separatist perspective.

Second, I’ve not sure how those who adopt Wang’s view solve this seeming contradiction: if the church is not to be involved in social ministry, how is social reform to happen as an eventual consequence of conversion?

After all, lay Christians will adopt similar attitudes as their teachers, who themselves emphasize ministries apart from society. Would movements like the Civil Rights Movement have happened if people had still maintained Wang’s views?

Click here to see the full issue of the journal. Leave a comment and let us know you thoughts.