The Bible is a collection of ancient texts. The most recent, by any reckoning, were written over nineteen hundred years ago. The oldest date back another five hundred to a thousand years and likely use sources dating back even further. They relate events that happened in the ancient world and were originally intended for an audience immersed in those long-ago cultures. As a result we rely on scholars to help translate that culture and bring it alive for us today. Only then will we get the most out of the text. The ancient understanding of the world provides a context for understanding the Scripture.

The Bible is a collection of ancient texts. The most recent, by any reckoning, were written over nineteen hundred years ago. The oldest date back another five hundred to a thousand years and likely use sources dating back even further. They relate events that happened in the ancient world and were originally intended for an audience immersed in those long-ago cultures. As a result we rely on scholars to help translate that culture and bring it alive for us today. Only then will we get the most out of the text. The ancient understanding of the world provides a context for understanding the Scripture.

It is uncontroversial that we better understand the covenant with Abram in Genesis 15 if we understand the cultural context of the ceremony related in this passage.

So the Lord said to him, “Bring me a heifer, a goat and a ram, each three years old, along with a dove and a young pigeon.” Abram brought all these to him, cut them in two and arranged the halves opposite each other; the birds, however, he did not cut in half… When the sun had set and darkness had fallen, a smoking firepot with a blazing torch appeared and passed between the pieces. On that day the Lord made a covenant with Abram and said, “To your descendants I give this land. (15:9-10, 17-18)

Halves of animals, birds, a firepot and torch? What does this represent? Unfortunately no clear cultural parallel seems to exist and we are left speculating a bit. In the Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary on Genesis John Walton offers a couple of suggestions involving a covenant ceremony, purification, or confirming signs, none of which he finds completely satisfactory. If we ever find evidence that makes better sense of the ceremony our understanding of the nature of the covenant will improve, although the main point is a covenant between God and Abraham and this is clear today.

Likewise we understand the story of Sarah and Hagar better when we realize that it was expected in the ancient Near Eastern context that a servant could be called on to produce an heir if the wife was barren. This wasn’t God’s plan for Abraham and Sarah as the story line makes clear, but it was an entirely acceptable practice well attested in contemporary literature. The same is true when Rachel provided Bilhah, her servant, to Jacob. There was nothing unusual in this practice and Rachel rejoiced that God had given her a son and named him Dan.

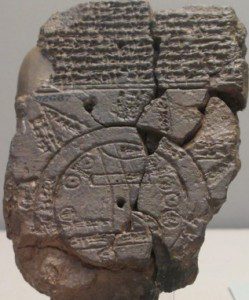

Although more controversial for some in the church, the same can be said for biblical cosmology. We will better understand the Scripture when we understand the ancient Near Eastern context in which it was written. This includes the cosmologies assumed in these cultures. Much has been learned about these cosmologies over the last couple of centuries from archaeological excavations all around the area and from the decipherment of the texts and inscriptions found on monuments and tablets. Unfortunately, it is difficult for the average Christian, or the busy pastor or teacher, to dig into the scholarly literature on the topic and as a result it is often ignored.

I recently received from the publisher a new book Scripture and Cosmology: Reading the Bible Between the Ancient World and Modern Science by Kyle Greenwood, associate professor of Old Testament and Hebrew at Colorado Christian University. This is a book written at an accessible level directed at lay Christians as well as pastors and teachers. Asked for the main point in this book Kyle’s responds:

I recently received from the publisher a new book Scripture and Cosmology: Reading the Bible Between the Ancient World and Modern Science by Kyle Greenwood, associate professor of Old Testament and Hebrew at Colorado Christian University. This is a book written at an accessible level directed at lay Christians as well as pastors and teachers. Asked for the main point in this book Kyle’s responds:

It is my contention that a high view of Scripture employs a hermeneutic that accommodates the biblical writers’ immersion in its ancient, pre-Enlightenment cultural context. As with other cultural matters, such as social customs and language, the biblical texts reflect that worldview in their written communication. So, I show how the ancient Hebrews thought of the cosmos as being constructed of three tiers: heaven, earth and sea. This viewpoint was not borrowed from surrounding cultures, but it was part of a shared culture among ancient Near Eastern people.

Greenwood quotes John Walton often in this book – and highlights Walton’s view that we need to understand that the Bible was written for us, but it was not written to us. The shared cultural milieu of the people to whom it was written shapes the book in ways that we don’t always appreciate and that translators sometimes brush under the rug. This is especially true when it comes to the creation accounts and the cosmologies assumed in a wide range of biblical passages. Likewise the cultural context of interpreters through the ages, including the likes of Augustine and Luther, has shaped the understanding of the church and the way in which we understand these passages today. Greenwood’s book digs into these issues on the edge between scripture and cosmology. The book isn’t written for scholars, rather “this book provides interested readers a single source for entering and engaging the world of ancient cosmology.”

Scripture in Context. Greenwood starts his book with a discussion of the range of contexts that are important in the interpretation of scripture.

- The cultural context. This includes the issues raised above concerning heirs through surrogates and the covenant ceremony. Greenwood uses the example of the use of the sandal when Boaz becomes the kinsman redeeming her. I expect that cultural norms are also involved when we read the negotiations between Abraham and Ephron son of Zohar for a burial cave. It seems a little strange to us, but likely seemed normal to the original audience.

- The geographical context. The political and natural lay of the land along with the local climate colors many of the stories in ways we only appreciate with study (maps and such) or experience. I have had a chance to travel to Israel a few times and I always come back with a better appreciation for what I read. I would love to be able to visit more of the Middle East some day, although political conditions make this seem unlikely.

- The historical context. Here Greenwood refers to the sequence of events and the experiences of the people. Exile and return from exile certainly colors large portions of the Old Testament. The realities of the Roman empire and the history leading into the first century colors the New Testament.

- The literary context. This includes such features as the structure of the message of a book as well as the genre of the book or passage. Faithful interpretation requires consideration of the sometimes uncertain structure and genre of each book and passage.

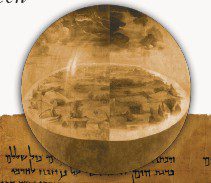

Part of the context for the Old Testament is the cognitive environment of the ancient Near East. The ancient Israelites, comprising both author and audience for the Old Testament, did not view the world the same way that we d0. Earth and moon and sun and stars did not conjure up the same image for them as it does for us. They certainly did not picture earth and moon as something like the image shown to the right nor did they have any inkling of the marvelous images of stars and galaxies we now see from the Hubble Telescope. They had a rather different phenomenological understanding of earth and sky and heavens. Something more like the lower view in the book cover.

Part of the context for the Old Testament is the cognitive environment of the ancient Near East. The ancient Israelites, comprising both author and audience for the Old Testament, did not view the world the same way that we d0. Earth and moon and sun and stars did not conjure up the same image for them as it does for us. They certainly did not picture earth and moon as something like the image shown to the right nor did they have any inkling of the marvelous images of stars and galaxies we now see from the Hubble Telescope. They had a rather different phenomenological understanding of earth and sky and heavens. Something more like the lower view in the book cover.

In first section of his book Greenwood runs through the available information on ancient Near Eastern cosmologies and then turns to the cosmology and cosmogony (i.e. theory of origins) contained in Scripture. We will look at these in the next post.

In first section of his book Greenwood runs through the available information on ancient Near Eastern cosmologies and then turns to the cosmology and cosmogony (i.e. theory of origins) contained in Scripture. We will look at these in the next post.

How important is context in the interpretation of scripture?

What questions does this raise?

If you wish to contact me directly, you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.