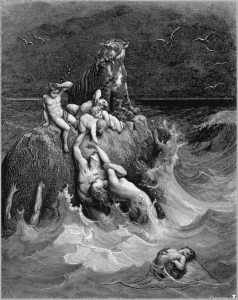

Although we think about the flood as a staple Sunday school tale, it is rather gruesome. We have not a cute progression of animals trekking to safety two by two, but a tale of utter destruction – of the undoing of creation as related in Genesis 1-5. Who would put a picture like the one to the right on wall of their nursery? But we concentrate on cute animals, gloss over the details, and marvel and the merciful covenant established by God signified by the beautiful rainbow.

Although we think about the flood as a staple Sunday school tale, it is rather gruesome. We have not a cute progression of animals trekking to safety two by two, but a tale of utter destruction – of the undoing of creation as related in Genesis 1-5. Who would put a picture like the one to the right on wall of their nursery? But we concentrate on cute animals, gloss over the details, and marvel and the merciful covenant established by God signified by the beautiful rainbow.

In reality, there are few passages in Genesis, or indeed in all of Scripture, that raise as many questions as the story of the flood in Genesis 6-8.

Who were the sons of God who “took wives for themselves of all that they chose?”

And how about the Nephilim … “the heroes that were of old, warriors of renown?”

What are we to make of the statement that “the Lord was sorry that he had made humankind on the earth, and it grieved him to his heart?”

Noah was the only one righteous among thousands and thousands?

Where did all the water come from?

How did the animals get to the ark?

How did they fit, including food for all?

How did they handle the waste?

Where did the animals get food after landfall? (Both herbivores and carnivores would have problems finding food.)

And this is only the tip of the iceberg.

The folks at Answers in Genesis have answers for all of these. The construction of The Ark Encounter, opening later this summer has forced them to address the questions. But frankly the answers are not consistent. Interestingly, one of the answers involves populating the Ark with “kinds” from which our current diversity of animals descended, with modification by natural selection … but don’t call it “evolution.” A cat kind, a dog kind, an elephant kind. This would require a rate of change in both genetic sequence and phenotype over only a thousand years or less that boggles the mind.

There is absolutely no evidence for a global flood covering the earth, or for a bottleneck in human and animal populations a mere four thousand three hundred and sixty three years ago. Human culture itself is far older, continuous, and dispersed around the globe. As just one example, John Walton notes in his Zondervan Illustrated Bible Background Commentary on Genesis that “no convincing archaeological evidence of anything approaching the size of the biblical flood has been uncovered.” Although there is abundant evidence for floods in Mesopotamia, the traces in different places have different dates. And “other cities whose occupation spans this time period (such as Jericho, continuously occupied from 7000 B.C.) contain no flood deposits whatsoever.” (p. 50)

But if we focus on the problems we will miss the intent of the original author/editor. The story of Noah and The Flood is included in the text of scripture for a reason. If we take scripture seriously we need to focus first on the message conveyed by the story.

Of the three commentaries we’ve been looking at, Tremper Longman III (Genesis in the Story of God Bible Commentary), John Walton (The NIV Application Commentary Genesis), and Bill Arnold (Genesis (New Cambridge Bible Commentary)), none conclude that the flood account in Genesis should be taken to refer to a literal global flood four thousand three hundred and sixty three years ago. Walton is the most conservative, taking the position that the flood was “global” not as we see the world today, but according to an ancient Near Eastern map of the world. No one in the ancient Near East viewed the earth as a globe in space. Arnold is the least conservative – seeing the account as a compilation from two Israelite sources, with reference to other stories and legends in the surrounding culture. Concerning the introduction in 6:1-4 referencing the sons of God and Nephilim he notes: “Clearly this little pericope has its origins in the traditional mythology of the ancient Near East. … By placing vv. 1-4 immediately prior to the traditional Israelite explanation for the flood (vv. 5-6) the editor has transformed it and used it to show why the flood was necessary.” (p. 90)

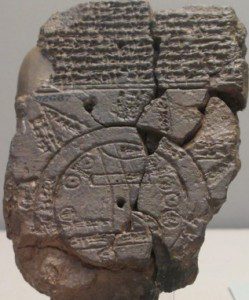

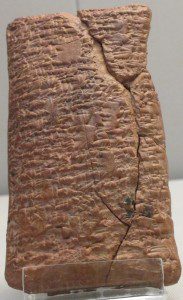

Of the three commentaries we’ve been looking at, Tremper Longman III (Genesis in the Story of God Bible Commentary), John Walton (The NIV Application Commentary Genesis), and Bill Arnold (Genesis (New Cambridge Bible Commentary)), none conclude that the flood account in Genesis should be taken to refer to a literal global flood four thousand three hundred and sixty three years ago. Walton is the most conservative, taking the position that the flood was “global” not as we see the world today, but according to an ancient Near Eastern map of the world. No one in the ancient Near East viewed the earth as a globe in space. Arnold is the least conservative – seeing the account as a compilation from two Israelite sources, with reference to other stories and legends in the surrounding culture. Concerning the introduction in 6:1-4 referencing the sons of God and Nephilim he notes: “Clearly this little pericope has its origins in the traditional mythology of the ancient Near East. … By placing vv. 1-4 immediately prior to the traditional Israelite explanation for the flood (vv. 5-6) the editor has transformed it and used it to show why the flood was necessary.” (p. 90)

Why a flood? There was, as Longman notes, “a robust flood tradition in Mesopotamian literature.” There is the mention in the Sumerian King List, the Sumerian story of Ziusudra, the Gilgamesh Epic, Atrahasis, and likely more. These have similarities with the biblical narrative in Genesis, but profound differences as well. The purpose of the story of Noah is radically different; it ties into the theme of Genesis 3-5 and sets the stage for God’s covenant with his people. There has been a proliferation of evil, beginning with the fall. We see a little of this with the story of Cain and Abel, and in the digression concerning Lamech (4:23-25). The proliferation of evil is made crystal clear in the prelude to our story.

Why a flood? There was, as Longman notes, “a robust flood tradition in Mesopotamian literature.” There is the mention in the Sumerian King List, the Sumerian story of Ziusudra, the Gilgamesh Epic, Atrahasis, and likely more. These have similarities with the biblical narrative in Genesis, but profound differences as well. The purpose of the story of Noah is radically different; it ties into the theme of Genesis 3-5 and sets the stage for God’s covenant with his people. There has been a proliferation of evil, beginning with the fall. We see a little of this with the story of Cain and Abel, and in the digression concerning Lamech (4:23-25). The proliferation of evil is made crystal clear in the prelude to our story.

The Lord saw that the wickedness of humankind was great in the earth, and that every inclination of the thoughts of their hearts was only evil continually. And the Lord was sorry that he had made humankind on the earth, and it grieved him to his heart. So the Lord said, “I will blot out from the earth the human beings I have created—people together with animals and creeping things and birds of the air, for I am sorry that I have made them.” But Noah found favor in the sight of the Lord. (vv. 5-8)

The story of the flood that follows is a story of uncreation (destruction) and re-creation culminating in a new covenant with Noah. In my discussion I will follow primarily Bill Arnold’s comments.

Noah’s righteous presence changes everything and nothing; that is, it changes nothing about the need for an expression of God’s justice, but it changes everything about our understanding of God’s mercy. The justice of God demands that a flood occur, but the grace of God allows an escape for Noah. (p. 98)

In the context of this story there are no other righteous people. Noah (and his household) is the only one. When God speaks to Noah in verses 11-13 this is made clear. The Hebrew text contains a play on words in the verb forms used. “In a way difficult to express in English, the use of this Hebrew verb illustrates that God’s actions are both unavoidable and just. Humanity has corrupted itself and there for God declares humanity corrupt (i.e. “destroyed”). (p. 99) God will judge the wicked, but he will establish a covenant with the righteous, in this case Noah v. 18.

By means of contrast with the unrighteousness of humanity at large, Noah’s covenant with God is given fuller meaning. Covenant-living in not only the means of survival (i.e. salvation) from the flood, but also the Bible’s answer to humanities sinful nature more generally. In this and other ways, Noah’s covenant anticipates and previews the covenant between God and Abraham, as we shall see. Righteous covenant-living will be highlighted as Israel’s hope for salvation, nationally and individually. (p. 101)

When the flood hits it is massive. All of creation is undone. But God himself has saved Noah and his household, shutting them into the ark (v. 16).

The cosmic phenomena described in 7:11-24 are not some banal punishment for the sin of that ancient generation., but they represent a reversal of creation, or “uncreation” as it has been called. The priestly creation account of Gen 1 portrayed creation as a series of separations and distinctions, whereas Gen 6:9-7:24 portrays the annihilation of those distinctions. As the sky dome was created to keep the heavenly waters from falling to the earth (1:6-7), here the opened “windows of the heavens” reverse that created function (7:11). When the “fountains of the great deep [tĕhôm]” burst forth (7:11), the cosmic order that had been fashioned from watery chaos returns to watery chaos (1:2,9). Strikingly the sequence of annihilation, “birds, domestic animals, wild animals, all swarming things that swarm on the earth, and all human beings” (7:21) follows closely that of creation itself in Genesis 1:1-2:3.

And then God remembers Noah and the animals – the center point or fulcrum of the story. In the Bible, “[w]hen God remembers, promises are kept, salvation delivered, old covenants renewed.” (p. 104) And a wind blows over the waters.

As the first part of the story moves toward chaos (6:9-7:24) , from this point forward it moves toward new creation (8:1-9:19). Indeed, a re-creation is signaled by the renewed separation of sea and land, the receding of waters, and the gradual appearance of dry ground in a way reminiscent of Gen 1, making complete the theme of creation – uncreation – re-creation (8:3, 7, 13) (p. 104)

There are more details that we could dig into in the story. But this is the broad stroke of the story.

There are more details that we could dig into in the story. But this is the broad stroke of the story.

Ten and one-half months after the flood began (7:11), Noah uncovered the ark and saw for himself that the ground was drying (8:13). His salvation complete, earth is now ready for new life. The age of a new world order is about to begin, and will be consecrated with new laws and a covenant in Gen 9. (p. 107)

Noah is the second Adam. A new covenant and a new start. But the story doesn’t change much.

Justice for the wicked and mercy for the righteous, those who live in covenant with God. This is the recurring theme of the Old Testament, and for that matter, the New Testament.

Perhaps, as John Walton suggests, the story recounts a real historical but local event, covering the whole world as known to the writer. More likely the story usurps a well known story of the ancient Near East and uses it to convey a message about God and his people. If there was a flood (and the story of a flood likely permeated the culture as common knowledge), it must have been from the LORD, both in the destruction and salvation. The primeval history of Genesis 1-11 is setting the stage for what is to come.

What are we to make of the flood?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net.

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.