To the casual observer one of truly odd features of late 20th and early 21st Century New Testament studies is that historical Jesus scholars (of the Jesus Seminar mode — Crossan, Funk, Borg) rejected apocalyptic as the context for explaining Jesus while some Pauline scholars (of the J. Louis Martyn mode — Martyn, Beker, Käsemann, Gaventa, Campbell) think apocalyptic is the context for explaining Paul. From the non-apocalyptic Jesus to the apocalyptic Paul. Another oddity: scholarship since J. Weiss, A. Schweitzer, and others up through folks like Dale Allison, have all thought Jesus was apocalyptic and not so much Paul. They may have thought the apocalyptic Jesus was irrelevant to moderns but they thought Jesus was absorbed in apocalypticism.

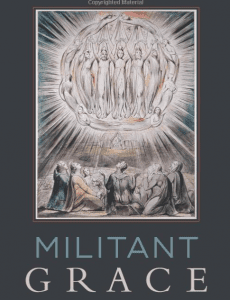

Theologians often pick up biblical scholarship and “theologize.” Combine Karl Barth (or the early Barth) and the apocalyptic Paul and you get a theologian like Philip Ziegler, and his new book, Militant Grace: The Apocalyptic Turn and the Future of Christian Theology.

Theologians often pick up biblical scholarship and “theologize.” Combine Karl Barth (or the early Barth) and the apocalyptic Paul and you get a theologian like Philip Ziegler, and his new book, Militant Grace: The Apocalyptic Turn and the Future of Christian Theology.

Let’s skip an important issue: Is “apocalyptic” in apocalyptic Paul and in the apocalyptic turn based on Jewish apocalypses and Jewish apocalyptic or not? N.T. Wright, for one, has made a pretty good case for calling into question the way apocalyptic Paul folks have used the term.

Let’s not skip, nor dwell on, another feature: the apocalyptic Paul and apocalyptic theologians have made this an either-or fight. Either apocalyptic or new perspective? Either apocalyptic or the old-new issues? It’s a false dichotomy for so many, including John Barclay who embraces many elements of old and new and apocalyptic. In addition, there are distinct features of the apocalyptic folks that are also found in NT Wright under categories like eschatology and apocalyptic.

At some point the claim that everything is new, or that it shatters everything prior to the revelation of God in Christ, etc, becomes so new it can’t make sense, so new that it sounds (if you’ll forgive me this one criticism) like the golden tablets of Joseph Smith), so new “Messiah” is divorced from the Story of Israel, and so new the discontinuity crushes the continuity that alone makes sense of what “new” means.

But I want to take a healthy look at Ziegler’s new book and sketch what he has to say. He goes to Beverly Gaventa to define apocalyptic gospel:

As Gaventa concisely puts it, “Paul’s apocalyptic theology has to do with the conviction that in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, God has invaded the world as it is, thereby revealing the world’s utter distortion and foolishness, reclaiming the world, and inaugurating a battle that will doubtless culminate in the triumph of God over all God’s enemies (including the captors Sin and Death). This means that the Gospel is first, last, and always about God’s powerful and gracious initiative.

Ziegler states it for himself:

To pursue an “apocalyptic turn” in Christian dogmatics is thus simply to learn anew what it means to “never boast of anything but the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, by which the world has been crucified to me, and I to the world,” as Paul wrote (Gal. 6:14). The effort, in short, is to do theology in a manner both shaken and disciplined by the “elemental interruption of the continuity of life” that the gospel is and brings about.

I came of age reading Ladd and Ridderbos; I see nothing in these two quotations that I did not see in their salvation historical approach to New Testament theology. I don’t see why old, new and apocalyptic — not to ignore participatory theology in Michael Gorman — can’t find far more common ground than disagreement. The battle in the coming decade ought to be for finding where we can agree.

Ziegler opens with a chapter that contrasts (radically) historicism (of the Troeltschian mode, but do folks adhere to that today? does he not have others in mind?) with apocalyptic theology. Historicism is “allergic to the eschatological” and in it there “is nothing but history” and that “theology exhausts its mandate in the practice of cultural analysis and criticism.” That’s nothing but a radical contrast. At the end of the chp he says historicism is “an intellectually sophisticated mode of unbelief.”

Now, an eschatological dogmatics will inevitably press hard on precisely th is neuralgic point, resisting historicism’s seeming evacuation of genuine transcendence. … For should we finally be forced to admit that salvation “can signify nothing other than the gradual emergence of the fruits of the higher life,” then closing time will truly have come to the bureau of eschatology, and the world will be left—falsely—to suffer under the chilling laws of its own aimless contingency.

Is all this about Troeltsch? No examples are given.

He finds an ally of his apocalyptic theology in the radical Lutheran theologian, Gerhard Forde. Terms like radical, catastrophic, death vs. life, radical discontinuity, radical break, neo-genesis, but perhaps “salvation by catastrophe” is his singular expression.

Apocalyptic theology is a struggle for transcendence in theological reflection, it is about ends — finality, grace is an ontology and not just eschatology, and monergism.

Ziegler’s contention is that this new apocalyptic theology must be embraced. But…

In view is a new kind of “apocalyptic theology” that overturns the high modern view of apocalyptic as a merely antiquarian curiosity while, at the same time, repudiating the weaponized eschatologies of soothsaying doomsday calendarists, often associated with popular varieties of “apocalypticism.” [Left Behind stuff]

This new sensibility is evident when graduating mainline seminarians are instructed that they must appropriate an apocalyptic “attitude” and “movement of mind,” because their ministry and the churches they will serve “can never make do or be legitimate . . . without the themes of the radical sovereignty of God and the exercise of that sovereignty through the cross and resurrection of [God’s] royal agent, Jesus Christ.”

Thus, re-enter apocalyptic as a theology of grace and gospel.

It represents an originary theological discourse with which Christians have described the world, and we in it, with relentless formative reference to the sovereign God of the gospel of salvation in Jesus Christ.

Ziegler rightly shows the significance of Karl Barth to this new kind of apocalyptic theology. How so?

For Barth’s early theology, as crystallized around the second edition of the Romans commentary, was marked by a volatile conjunction of themes that together fill out the meaning of the Krisis (the radical crisis) that Paul’s gospel represents: the radical priority of divine agency in salvation, the uncompromisingly “vertical” or transcendent nature of God’s action, the real evangelical power of God—a theme taken up from the Blumhardts—the inviolate particularity of the incarnation, and the sharp contrast between the old on which God’s grace and Spirit fall, and the new thing brought into being thereby.

All of this is what Barth meant by “eschatology.” Barth is clearly influential in deep ways on Käsemann and J. Louis Martyn, and then on all the apocalyptic theologians mentioned above. Martyn’s big influence was retrospectively rethinking everything in light of the death and resurrection. In this approach, at times — too often — Jesus is turned into an event (cross, resurrection) and personhood, incarnation, etc., are diminished or ignored. McCormack contends this approach has the weaknesses of the early Barth vs. the later forensic Barth. Ziegler presses on to Walter Lowe, Nate Kerr (critical) and Douglas Harink — who appropriates Barth into an apocalyptic framework.

So Ziegler proposes the following six theses on apocalyptic theology:

1. A Christian theology funded by a fresh hearing of New Testament apocalyptic will discern in that distinctive and difficult idiom a discourse uniquely adequate both to announce the full scope, depth, and radicality of the gospel of God, and to bespeak the actual and manifest contradiction of that gospel by the actuality of the times in which we live.

2. A Christian theology funded by a fresh hearing of New Testament apocalyptic will turn on a vigorous account of divine revelation in Jesus Christ as the unsurpassable eschatological act of redemption; its talk of God and treatment of all other doctrines will thus be marked by an intense christological concentration.

3. A Christian theology funded by a fresh hearing of New Testament apocalyptic will stress the unexpected, new, and disjunctive character of the divine work of salvation that comes on the world of sin in and through Christ. As a consequence, in its account of the Christian life, faith, and hope, it will make much of the ensuing evangelical “dualisms.’

4. A Christian theology funded by a fresh hearing of New Testament apocalyptic will provide an account of salvation as a “three-agent drama” of divine redemption in which human beings are rescued from captivity to the anti-God powers of sin, death, and the devil. In addition to looking to honor the biblical witness, this is also, it is wagered, an astute and realistic gesture of notable explanatory power.

5. A Christian theology funded by a fresh hearing of New Testament apocalyptic will acknowledge that it is the world and not the church that is the ultimate object of divine salvation. It will thus conceive of the church as a creation of the Word, a provisional and pilgrim community gathered, upheld, and sent to testify in word and deed to the gospel for the sake of the world. Both individually and corporately, the Christian life is chiefly to be understood as militant discipleship in evangelical freed om.

6. A Christian theology funded by a fresh hearing of New Testament apocalyptic will adopt a posture of prayerful expectation of an imminent future in which God will act decisively and publicly to vindicate the victory of Life and Love over Sin and Death. The ordering of its tasks and concentration of its energies will befit the critical self-reflection of a community that prays, “Let grace come and let this world pass away.’