Editor’s Note: Christian Campgrounds seem to have become a theme around here lately, what with Camp Redemption by Raymond Atkins and all. (Tim read it and enjoyed it as well.) Today’s guest post is by the bright and beautiful Jolina Petersheim, whose parents ran a Christian camp. I’ll let her tell you all about it, but once you finish Jolina’s post, hop on over to her website and check out her other stories, and be sure to get your hands on Jolina’s debut novel The Outcast, Amish fiction with a twist of cultural reality.

Growing up, our parents were caretakers on a three hundred sixty-five acre Civil War-era farm that had a fifty-acre portion turned into a Christian campground, with cabins, a bathhouse, and a main hall. But my older brother, James, and I were not interested in the outbuildings.

The land was what held our fancy: lush, rolling, and ribboned with spring-fed creeks, it was a childhood paradise.

If we traversed an acre a day, it would take an entire year to explore it. But we tried. Oh, how we tried. Rain or drought, summer or winter, together James and I built forts, dams, bridges. We scrambled across the wet bellies of caves and filled our pockets with pirate treasure: arrowheads, dinosaur eggs (rocks), Indian money (fossils) and, once, a human tooth.

We did not know our childhood was unusual. In the beginning, when our family first moved onto the camp, my brother and I shared a bedroom in a remodeled slave quarters that was divided down the center with a strip of Duct-tape.

Our next-door neighbors were wealthy Jesus people left over from the Summer of Love. I loved to stare at them: tan, barefoot, and lean with matching crisp bib overalls and a crop of wild silvery hair. They approached farm life with the zest of having been freed from the city.

They purchased a tractor and hired my dad to build a barn. I visited their newly-built home and marveled at their Jacuzzi tub and purple walls trimmed with scrollwork like icing. Our bathroom in the slave quarters was converted from a closet. You could brush your teeth and scrub yourself down at the very same time.

Our neighbor’s yard crackled with gray geese and speckled Bantam chickens. Rescued sheep dogs panted under their front porch. Clydesdales stood in the field we shared, flicking off flies with their luxurious, caramel-colored tails.

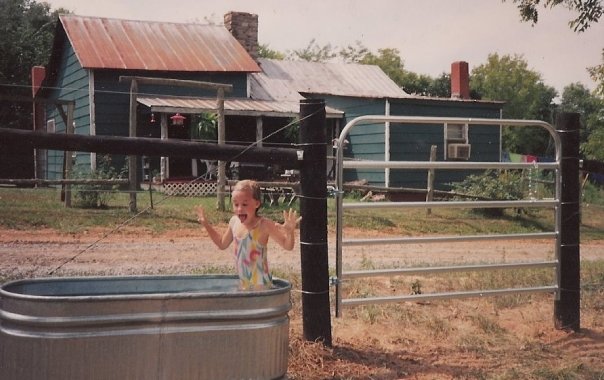

My brother and I watched the Clydesdales while swimming in the horse trough we filled with cold water pumped in from a garden hose. We were young enough to think that summer took up half of our lives and that the school year didn’t actually slip by on a continuous string.

Then, seemingly overnight, my brother’s voice deepened, his whiskers sprouted, and he didn’t want to build forts or swim. At VBS, he was caught in the graveyard with a gang of boys: all slanted against tombstones and smoking Marlboro Lights while I sat at a table inside, obliviously sipping Kool-Aid from a Styrofoam cup.

James withdrew from me, and I withdrew from him. Our latest fort got overtaken by weeds, and the crumbling seemed to correspond with the crumbling of the camp’s utopian foundation.

Irrevocable differences between the camp owner and its inhabitants caused our hippie neighbors to move away; their once raucous barn devoid of anything but moldering hay and feathers. Our family was asked to leave too, but we remained: the camp’s unspoken outcasts.

James and I were told that we could no longer explore. Our dogs had to remain chained in our yard. My parents’ volunteer caretaking work load increased, but they said we would not give in. We were called. We would not move from the home my father had built with his father’s inheritance.

A creature of habit, I was relieved that nothing had to change. My brother was enraged. He spouted about vandalism and went hiking through the woods regardless—a gun slung over his back, his jaw tight. I did not want to trespass, even if those hills beneath his feet were as familiar as the backs of my hands. I wanted to be liked; I wanted to fit in. So I stayed in my pink bedroom and read until the sun left a faint smear across the window panes.

Like the Robert Frost poem, in our childhood stomping ground—more enchanted for being forbidden—James and I saw that two roads diverged in a yellow wood: a path of ease, and a path of hardship. At the time I thought he’d taken the latter, but now I am no longer sure.

James was the one who, two years later, gunned his truck up the steep hillside and came grill to grill with the owner of the camp. I wasn’t there, but I can imagine how the bills of their salt-stained caps shielded their eyes; how their skinny bodies and tempers sizzled and ticked as much as their vehicles’ engines.

In contrast, at fourteen years old, I was the one who walked from door to door at the camp with my best friend beside me. Weeping, I told her that I wanted to say goodbye, that I wanted closure before we closed the camp gates for the final time and left. But I think that I wanted their stamp of peace-making approval, and therefore the stigma of the outcast revoked.

Our family moved three miles up the road. My brother stayed out later and later at night. After a party, he slammed his blazer into a tree—cracking the windshield, his teeth, his lip. He was hospitalized in case of a coma. I went to visit him and saw the stitches, like spiders marching from his nose to his chin. He was in the midst of being transformed into someone I didn’t recognize. But I was being transformed as well.

My brother graduated from high school and kept his job changing oil. I became a cheerleader, then the head cheerleader, the vice-president of the senior class. My brother dabbled with substance abuse. In college, I became a cheerleader, a staff reporter, resident assistant, campus ambassador, homecoming queen. . . .

The deeper James plummeted into drugs and alcohol, the harder I spun—determined to stay out of his orbit, out of his path. But, we were actually not traveling too far apart. I told myself that I would never go to such a drastic extent to feel nothing. Yet now, looking back, I wonder if all of my spinning was meant to keep from feeling my own outcasted pain.

This spring, my brother James came to visit my husband and my home. He brought his four-wheeler on the back of his work truck and revved it to life before we had even finished dessert.

“Wanna come?” he asked.

I had dishes in the sink and a baby girl who would soon need changed. And yet, I thought of us back then. I thought of our childhood, and all those times he would head into the camp’s forbidden woods alone because I was too worried about what others would think to follow.

I wiped apple suds on my skirt and nodded. James grinned.

I hung my Sunday best in the closet, tied my hair into a ponytail, and laced up running shoes. Outside, James clambered onto the four-wheeler, and I wrapped my arms around his lean waist.

“Hold on!” he cried and thumbed the throttle. Drizzle stung my eyes. The wind whipped over our heads like we were flying. I pressed the side of my face against his back and held on tighter.

We’re here, I thought. We’re really here.

And this time, we weren’t spinning in separate orbits. This time, we were holding on for dear life as we both moved forward.

*My brother’s name has been changed to protect his identity.