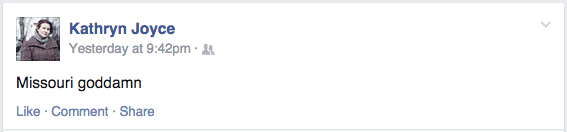

I first received news of the grand jury decision in Missouri Monday night from my Facebook feed. It was a status update only two words long:

I knew what had happened immediately, and my stomach turned over.

I opened twitter and began reading what was posted under #Ferguson, paying special attention to updates by people of color and those on the ground, including @Nettaaaaaaaa, @deray, @drgoddess, @WyzeChef. I learned of massive police action, and of rioting. As the grand jury report came out, I learned that the prosecutor had flat out lied to the grand jury, that the medical examiner who examined Mike Brown’s body took no pictures, and that Darren Wilson described Mike Brown as looking like a demon. I read the anguish and righteous anger of people of color, and I cried. I felt so powerless.

The next morning I logged back into twitter for an update on how things were going, and my uncle walked in and asked if I was checking on how things were in Ferguson. I said I was, and the conversation that ensued was tense. My uncle defended the grand jury decision, insisted that if you go looking for racism of course you’ll find it, and finally said that black people are racist against white people. I very much objected. I told him that studies have found that people are more likely to pull a trigger on an unarmed black man than an unarmed white man, that resumes with black sounding names are less likely to be called back than resumes with white sounding names, and that black men get harsher sentences than white men for drug offenses. When he didn’t believe me, I offered to get him the links.

His next response?

“You sound like Al Sharpton.”

His tone was one of dismissal.

I was angry. I told my uncle that Al Sharpton really isn’t my generation, but honestly, mostly I was angry because I have plenty of experience with family members dismissing my views as me turning my brain off and copying others and not recognizing my ability to form my own ideas. I told him I have formed my opinions on this matter from reading blogs by people of color, listening to people’s lived experience, doing my own research, and studying the history of racial conflict in our nation. I told him I was not ignorant or simply being “politically correct.” For once, I felt unafraid.

But then later in the day my father walked into the room and said “I need to check on how things are going in Ferguson.” I picked up my laptop and fled to the other side of the house post haste. I can’t argue about something like this with my father. Perhaps I am a coward. Perhaps I need to do more. I don’t know. What I do know is that he and I have a history, and that as a result of that history any conversation I have with him that even touches on politics spikes my blood pressure and sends me into a downward emotional spiral. I knew what would have happened, that I would have been angry and that he would have dismissed me as emotional. And so I fled.

There was a time I thought like my father, and like my uncle. Like them, I believed racism was a thing of the past. I thought I was “colorblind,” and that black people were disproportionately stuck in poverty because they were lazy. I talked about “the race card” and believed that black people held themselves back through a victim mentality. In other words, I believed that black people—not white people, not structural inequality—were the problem. Then one day I became an adult and found that much I thought I knew was wrong, or built on faulty perceptions. So I listened, and I learned, and I grew. I wish there was a way I could prod my uncle or my father to do the same, but then, they have been adults for decades and are set in their ways of thinking in a way that I, as a young adult when my perception shifted, was not.

When Sally started kindergarten this year, it meant a new new school and new friends. Sally frequently told me about a girl in her class named Louisa, describing her as the tallest child in the class. Several months into the fall I met Louisa, a lanky little black girl with braided pigtails, while dropping something by the school. This struck me as interesting, because the most important thing about Louisa’s appearance, for Sally, was not her race but her height. It would be easy to wax lyterical about children being colorblind, but it can’t end there, because race does matter. I was raised by parents who believed they were colorblind, but did not recognize the way race affects people’s experiences in this country.

I remember a time when I was an undergraduate, when my college’ s football team played their main rivals at their home stadium. This game was a really big deal, probably a qualifying match of some sort. In case it’s obvious, I know very little about sports in general and football in particular, but I do remember this game. I remember it because the residence hall I lived in was immediately between the stadium and campus, and the residence hall directors were worried that post-game rioting might pose a safety threat to our residence hall. The topic was discussed at length at a hall council meeting and additional safety steps were taken to ensure that should rioting ensue, our dorm would not be breached. In the end, the feared rioting did not occur. But the residence hall directors weren’t worried for no reason.

White people riot too. We riot over sports. I abhor the white narrative that if black people riot, it somehow legitimizes the injustice that provoked their rioting. But there’s other things, too. For example, whites and blacks do drugs at similar rates, but black individuals are far more likely to be arrested and sentenced for drug offenses than are white individuals. Both black people and white people riot and do drugs, but when they do so they are perceived differently.

I have no idea where we go from here, and it’s not my place to determine that. I do know that I have been truly inspired by the bravery and honesty of the people of color I follow on twitter and on the blogosphere.

Feel free to suggest more voices to follow. Staying informed is important.