Last week I wrote a post commenting on an article titled Motherhood: The Strongest Bond, writer Denise Stirks. Denise argued that moms have a special bond born of their love for their children. She talked about the empathy she feels for other moms, whether it be a mom trying to quiet her baby on an airplane or a mother trying to arrange childcare so that she can cover her shift. She spoke of this bond and common empathy for other mothers as though it is universal and almost magic.

I critiqued the article by pointing out that while I am a mother, I have also been a child—and for whatever reason, I haven’t forgotten what it was like to be a child. As a result, I am just as likely to feel a common bond and empathy for children as for their mothers. I noted how difficult childhood is and queried why we as a society don’t have greater empathy for children.

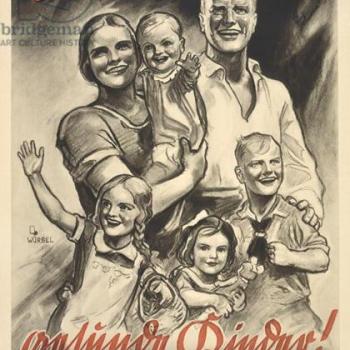

Some of my readers pointed out that there was another issue that I left unaddressed—an issue I will call “the mommy myth.” In her article, Denise focused on a common bond among mothers, born out of their affection for their children. In her title, she called this “the strongest bond.” This idea is not new. It’s very common in our society today to place mothers on a pedestal. Of course, this pedestal is often limited to white, married women, and it doesn’t come with things like paid maternity leave or social security benefits for stay-at-home mothers. But still, the rhetoric is strong.

There are several problems with the mommy myth.

First, it leaves out children’s other caregivers and assumes that mothers bond with their children in a way no other individuals do, including fathers. But of course, this isn’t just about fathers—there are also aunts, uncles, grandparents, teachers, daycare workers, and other adults who befriend children. I reject the idea that fathers are less capable of bonding with their children than are mothers. Of course, I also don’t think parenthood is necessary to developing either strong affection or deep empathy for a child.

Second, the mommy myth assumes that all mothers are good, caring, and loving. It assumes that giving birth to a child changes a woman so completely that she can’t do other than love her child. This is false. There are plenty of mothers out there who don’t love their children, and mothers who abuse or neglect their children. Being a mother does not magically make a woman a good caregiver. As long as we hold this assumption that motherhood somehow bestows goodness, we will be unable to recognize or take proper protections against maternal abuse and neglect.

I say all of this as a mother myself. I love my children so much it hurts. But at the same time, I don’t think my love for them is any more powerful than (or even all that different from) the love my husband feels for them. And then, of course, my children have aunts, uncles, grandparents, childcare providers, and teachers in their lives—and other adults as well. While the amount of affection and attachment each of these individuals feel toward my children may vary, I refuse to use my bond with my children to downplay the bonds other adults form with them. Indeed, I am extremely grateful for the large number of adults who invest in my children and come alongside my husband and I to love and treasure them.

Where does the mommy myth come from? Two places come to mind.

We live in a society that rejects the idea that it takes “a village” to raise a child. We elevate parents as special, as uniquely capable of loving and investing in children. As we do so, we devalue the role played by teachers and other caregivers, and the role played by aunts, uncles, grandparents, and other family members. This idea that parents should (or do) go it alone in raising children is a problem. Parents need support—and children need multiple adults investing in their lives.

And then, of course, is the patriarchal idea that women’s primary role and purpose in life is that of mother. The result is a devaluing of women who do not have children. And, because women are assumed to be natural nurturers and caregivers while men are assumed to be natural protectors and providers, the result, too, is a devaluing of the love fathers have for their children. This idea is a problem both because it devalues fathers’ investment in their children and because it places mothers on a pedestal that renders their actions unquestionable—because we know that all mothers love their children, right?

Okay, story time. I once fell down a flight of stone steps with Bobby on my shoulders. During the fall I somehow moved Bobby from my shoulders to a protective space within my arms; this was instinctive rather than thought through. After the fall Bobby was fine, though slightly frightened. In contrast, I skinned my knees and elbows so badly that blood was trickling down my legs and dripping from my arms. I have in the past attributed my instinctive protection of Bobby at my own expense to a sort of “mommy spidey sense,” but now that I think about it I’m pretty sure my husband’s instincts would have been the same—and I suspect the same is true of many (if not most) of the other adults in my son’s life as well.

What about the science? Many studies of maternal instinct fail to also study other adults in a child’s life. How this oversight is not obvious I have no idea. Of course a mother would react more strongly to seeing her own infant upset than to seeing another infant upset—I would suspect the same to be true of an aunt and niece or nephew, and a grandparent and grandchild, and so forth. A recent study found that “the ability of a parent to identify their child’s cry was determined by the amount of time they spend with the baby, not by their gender”—but of course, this study, too, failed to include a child’s other caregivers.

The mommy myth is harmful a number of levels. It devalues the critical role other adults play in children’s lives, treats the love of a mother as greater or more important than the love of a father, and makes it harder for us, as a society, to recognize or deal with abusive and neglectful mothers. We need to stop placing mothers on a pedestal. Mothers don’t need deification, they need community support and accountability.

It’s time we laid the mommy myth aside.