Last week I asked asked you to vote on of three works of Christian fiction I should review here. I just read through that entire thread tabulating your votes, and A Voice in the Wind received more votes than both The Vision and Forbid Them Not combined.

Now, several of you expressed concern that A Voice in the Wind may be less fun to review because Francine Rivers is widely accepted as a good writer. I think that will probably be offset by both her gender politics and the historical setting she creates. Also, several you mentioned another of Rivers’ books, Redeeming Love. I thought I’d let you know that Samantha Field is currently reviewing that book over on her blog. I think I skimmed it as a teen, but it was my sister’s favorite, not mine—myself, I was so obsessed with A Voice in the Wind that I actually planned to name my first daughter Hadassah.

Several of you also mentioned Frank Peretti’s Cooper Kids series. Oh my gosh, guys, you really took me back! I spent way too many hours trapped in a claustrophobic underwater structure, evading poisonous flying slugs, trying not to be blown do smithereens in a random volcanic eruption—and what even was that huge wall thing that randomly appeared in a desert? I’m just saying, Jay and Lila were my homies. I mean who wouldn’t want to accidentally almost release the locusts of the future tribulation? (And yes, I just typed all this up without looking up the book titles to jog my memory.)

All that said, let’s get started.

A Voice in the Wind, pp. 3-13

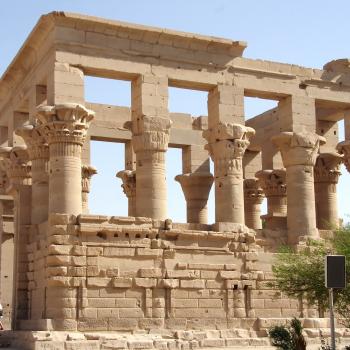

The book opens with the siege of Jerusalem. The year is 70 A.D. The bit of digging I did suggests that the history Rivers lays out here tends to be accurate. The Jews had rebelled against the Roman Empire, but they were divided between various leaders and factions, and fought amongst themselves. The Romans laid siege to Jerusalem, and the various Jewish factions united in opposition, but it was too late—and the Romans waited for famine to take hold. That is where we meet our young heroine.

Hadassah and her family are in Jerusalem. According to Josephus, Jews who had come to Jerusalem to celebrate passover found themselves trapped inside the city when the siege began. Hadassah’s family had come there, then, from their home in Galilee, but not to celebrate the passover, for they were Christians. They came to meet with other “believers of the Way,” as Rivers calls them.

Few believers of the Way remained in Jerusalem. Many had been prisoned, some stoned, even more driven away to other places. Lazarus, his sisters, and Mary Magdalene had been driven out; the apostle John, a dear family friend, had left Jerusalem two years before, taking the Lord’s mother with him. Yet, Hadassah’s father had remained. Once a year, he had returned to Jerusalem with his family to gather with other believers in an upper room. There they shared bread and wine, just as their Lord Jesus had done the evening before his crucifixion.

According to Diarmaid MacCulloch’s history of Christianity, on page 206 and 207, when the rebels took control of Jerusalem the Christians community there left the city voluntarily:

The Jewish Christian Church, interestingly, fled from the city; it was distant enough from the world of Jewish nationalism to wish to keep out of this struggle. … After the revolt of 66-70 no substantial Christian community returned to Aelia/Jerusalem until the fourth century.

This may seem like a nitpick, but I would make two larger points.

First, evangelicals frequently exaggerate the persecution early Christians faced, as part of a greater persecution/martyr complex. It’s not that these early Christians did not face persecution—they absolutely did. But it was neither as constant nor as straightforward as evangelicals frequently portray it. In Rivers’ telling, the last of the Christians in Jerusalem were driven out by persecution; as MacCulloch tells it, the last of the Christians in Jerusalem fled to avoid a war they wanted no part in.

Second, my sources are telling me that the Jews who traveled to Jerusalem for Passover and became trapped by the siege were especially observant Jews. It was clear that there was trouble in the country, and danger, but they went to Jerusalem anyway, because it was Passover. Christians like Hadassah’s family would have been unlikely to go there—the Christian community there had fled, after all. Still, I think I know what is going on here. Rivers wants a Christian heroine who begins the book as a captive following the siege of Jerusalem. To do that, she has to get her Christian heroine into Jerusalem and trap her there.

What Rivers describes Hadassah’s family participating in (and she does give a full description) is not just an early celebration of the eucharist (or communion). It’s also a full passover meal, with the lamb, the unleavened bread, and the bitter herbs. So I checked, and lo, early Christians living in the east did celebrate passover, observing it on the same day as the Jewish passover. This became quite a controversy when the Christians living in the west, such as those in Rome, switched to celebrating Easter, and on a Sunday.

Hadassah’s father told his story at the gathering, especially for the benefit of new Christians gathered there but also for those who had heard it before. Hadassah’s father was the boy whom Jesus raised from the dead when he came upon his funeral procession and his weeping mother. Hadassah was transfixed—Rivers tells us she never tired of this story.

Rivers tells us other things about Hadassah, though, not all of them so positive—or at least, not all of them so positively framed. Hadassah, you see, was afraid. She didn’t like it when, on their way back to the house where they stayed in Jerusalem, her father would stop and preach to the crowds.

The euphoria and security she felt with those who shared her faith dissolved when she watched her father stand before a crowd and suffer their abuse.

Here’s the thing—Hadassah’s fear is reasonable.

Two years ago he had been so badly beaten that two friends had to help carrying him back to the small rented house where they always stayed [when they went to Jerusalem for Passover].

After that, his friends had urged him not to return to Jerusalem, telling him that there were many there who wanted him silenced. They told him to go preach somewhere else, that even Lazerus had left to preach elsewhere, but Hadassah’s father refused to listen. “I cannot leave Judea,” he had said. “Whatever happens, this is where the Lord wants me.” It is no wonder Hadassah is afraid.

Rivers tells us that in “the peaceful hills of Galilee” Haddassah could believe. “At home, in those hills, her faith was strong.” But in Jerusalem? In Jerusalem “she struggled,” Rivers tells us. “Doubt was her companion, fear was overwhelming.” Fear, apparently, leads to doubt. Afraid, Hadassah argues with her father.

“Father, why can we not believe and remain silent?”

“We are called upon to be the light of the world.”

“They hate us more with each passing year.”

“Hatred is the enemy, Hadassah. Not the people.”

“It is the people who beat you, Father. Did not the Lord himself tell us not to cast pearls before swine?”

“Hadassah, if I am to die for him, I will die joyfully. What I do is for his good purpose. The truth does not go out and come back empty. You must have faith, Hadassah.”

Hadassah had argued, again, the last time she saw her father.

“Why must you go out again and speak to those people? You were almost killed the last time. … Please, don’t go. Father, you know what’ll happen. What’ll we do without you?”

There are three children in the family—Hadassah, her brother Mark, and their little sister Leah. The whole family is trapped inside Jerusalem, trapped by a Roman army, trapped inside a city occupied by Jewish nationalists, trapped inside a city fast running out of food. And still her father says no, that he must go, that he must speak.

Grabbing and shaking her mother, Hadassah had pleaded, “You can’t let him go! Not this time!”

“Be silent, Hadassah. Who are you serving by arguing so against your father?”

Her mother’s reprimand, though spoken gently, had struck hard. She had said many times before that when one did not serve the Lord, they unwittingly served the evil one instead. Fighting tears, Hadassah had obeyed and said no more.

That was the last time Hadassah ever saw her father. He did not come back.

Rivers describes the effects of the famine on Hadassah’s family in detail that is difficult to read. Her gaunt mother is no longer responding. Her emaciated little sister, Leah, is lying in the corner on a dirty pallet. Her brother Mark is off scouring the city looking for something to bring back for them to eat—but comes back empty handed. Hadassah begins to cry. Young Mark begins describing things that no child should see—dead bodies thrown into piles. Hadassah asks why they must suffer. Mark answers.

“We bear the consequences for what we have done to ourselves, and for the sin that rules this world. Jesus forgave the thief, but he didn’t take him down off the cross.” He pushed his hand back through his hair. “I’m not wise like father. I haven’t any answers as to why, but I know there is hope.”

“What hope, Mark? What hope is there?”

“God always leaves a remnant.”

And that is where I’m going to leave us, this week.

Rivers is setting up Hadassah’s fear as something she will overcome later in the book, but from where I’m standing her fear, at this moment, seems perfectly reasonable. Indeed, while they didn’t have the term back then, I’d imagine living through the siege, famine, and sacking of Jerusalem would give someone some serious PTSD. This isn’t a faith issue. It’s a living-through-things-no-child-should-live-through thing.

And while we’re at it, let’s talk about Hadassah’s father. Could he not see that it was traumatizing to Hadassah to see her father beaten, to fear for his life on a daily basis? And what about the fact that his desire to preach the gospel left his wife and three children alone in a besieged city? This is, of course, a common evangelical narrative—the idea that preaching the gospel is worth risking all things, including one’s life. But what of the children who bear the effects of such actions? Is it fair to ask this of them? Hadassah isn’t given a choice. In fact, when she begs her father to stay with them, and not leave, she’s literally accused of serving Satan. She’s a child. She wants her daddy safe, and with her family. And that, apparently, is the same as serving Satan.

There’s also the idea that fear leads to doubt. It’s sort of like in Star Wars, I guess. Fear leads to anger, anger leads to the dark side. Fear leads to doubt, doubt leads to serving Satan. We need to figure out a better way to talk about fear, because this ain’t it.

And now I’m out of time! More next week!

I have a Patreon! Please support my writing!