Blogger Jonny Scaramanga recently published a piece examining the ACE curriculum’s treatment of the civil rights movement. ACE stands for Accelerated Christian Education; the program was developed in the 1970s to allow Christian schools to set up in church basements without the need for teachers (in ACE schools, students read through workbooks at their own pace at individual student cubicles). What Scaramanga found when he looked through ACE’s social studies workbooks offered ample cause for concern.

Scaramanga examined at the ACE social studies workbooks that form the final installments of ACE’s 8th grade course in U.S. history. The workbook for 1945-1969 was comprised of roughly 13,000 words and made no mention of Rosa Parks, Malcolm X, or numerous other civil rights giants. In fact, neither it nor the previous workbook mentioned racism, the KKK, Jim Crow, or lynchings. As Scaramanga noted:

And you must understand that ACE is designed to be a self-contained curriculum. The workbooks contain everything you need to know to complete all the activities and to score 100% on the test. They are not expected to be a starting point for further inquiry, or to be supplemented with additional materials. For most ACE students, if it’s not in the book, they just don’t learn it. Which means most ACE students have next to no cultural knowledge of racism.

It goes without saying that this is a problem—and it’s not just ACE. I have spoken with homeschooled high school students who didn’t know what the civil rights movement was, or about Jim Crow laws. The history we don’t know shapes us just as much as the history we do know. Consider how the Black Lives Matter movement might appear to someone who literally did not know that our country had ever had a problem with racism.

What about Martin Luther King Jr.? Surely the ACE curriculum at least covers him, right? Well, yes. According to Scaramanga, the text devotes 345 words to King’s life and death, focusing mostly on his assassination—in fact, Scaramanga writes that “there’s an entire paragraph about King’s assassin James Earl Ray, which is actually longer than the expository paragraph about King.” Furthermore, the text never quotes from any of King’s speeches.

And, as Scaramanga explains:

And then, the pièce de résistance:

The response to Dr. King’s death was violent. Angry young blacks rioted, robbed, and burned buildings in several American cities. All of this was done in the name of a man who wished to be remembered as a man of peace.

So ACE, lemme get this straight.

(a) You didn’t have space to quote from any of King’s speeches but you did have space to make sure we read about those angry young blacks who are rioting (because that’s what black people do, amirite?).

(b) Admit it, ACE author: you’ve never read a thing King wrote, have you? And you’ve never heard a word he spoke other than that decontextualised bit from “I Have a Dream” which we all love to use to make out his message was nothing but butterflies and moonbeams.

(c) Because you’ve never read a damn thing King wrote, you don’t know that he said “we’ve got to see that a riot is the language of the unheard”. If you did, maybe you’d think about this context. Perhaps you’d think about how you’d respond as a black person on learning that your best chance of being heard was just assassinated.

Scaramanga compares ACE’s treatment of rioting following King’s assassination to its treatment of school integration, or as ACE chose to term it, “forced busing.” Scaramanga provided us with this section in full:

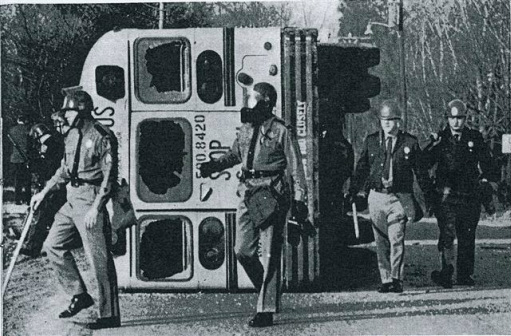

In 1969 the Supreme Court had ordered immediate integration of schools, which meant many school districts had to bus students to schools outside their neighborhoods. This practice was legal according to the 1971 Supreme Court case of Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education. Busing meant that black students were sometimes bused into white neighborhood schools, and white students were sometimes bused into black neighborhood schools. Partly due to the problems of busing, violence sometimes erupted. During President Ford’s administration, violence over forced busing of government school students continued to surface. In 1974 there were violent demonstrations in Charlestown, a small town outside Boston, Massachusetts. In 1975 the National Guard was called to stop a demonstration in Louisville, Kentucky. Both demonstrations were the result of the forced busing of government school students.

As Scaramanga points out, there is a complete lack of “who” in this section. Violence, instead, is given agency. Violence simply “erupts” and “continues to surface” and that this is “due to the problems of busing.” What these “problems” are we are not told. In contrast to the earlier section where we were informed that “[a]ngry young blacks rioted, robbed, and burned buildings” after King’s death, we are not told who carried out this violence or what they did.

The text states that “there were violent demonstrations” in Charlestown, outside Boston. It does not state who did the violence, or why. In fact, if you didn’t already have some familiarity with the topic you might assume that black parents were just as likely to be upset over their children being bused to other neighborhoods as white parents.

What exactly did happen in Charleston, outside Boston? Well.

White people. White people rioted. White people threw rocks at school buses full of black children. White people boycotted their assigned schools. White people beat up black people. Because of white people, black children feared for their lives. Stay away from the windows, bus aids and police escorts told them. “It was like a war zone,” as one black student bused to a white school put it. White people did this not “due to the problems of busing” but because they were racist.

Heck, Nazis showed up from Virginia to protest Boston’s busing plan.

This reaction was not inevitable or foreordained. Some of the most interesting stories in a Boston Globe article forty years after the riots and violence are about the white students who didn’t have a problem with being bused into black schools, the ones from integrated neighborhoods who showed up anyway and were upset not by their new classmates, whom they quickly set to getting to know, but by the media, which wouldn’t leave them alone. Students like Eileen Dunner.

What about Louisville? The ACE curriculum text states that: “In 1975 the National Guard was called to stop a demonstration in Louisville, Kentucky.” Who held the demonstration is not mentioned, nor is why the National Guard would be necessary to stop a “demonstration.” Well. Here’s what happened:

[O]n Thursday, September 4, 1975, the school district began to integrate. The first day was extremely tense, but more peaceful than originally anticipated. Unfortunately, that peace did not last. The Chicago Tribune reported that the next day, 10,000 students “ran out of control at a suburban high school,” where they set fire to buses and threw rocks, injuring almost thirty cops. One black student reflected, “As students we had bricks, rocks, bats, sticks, fists, spit, and profanity hurled at us and our bus drivers as we transitioned from the school to the bus. We were powerless. We struggled to understand the madness, but we knew that busing us across the county was means to end. We were on the heels of the civil rights movement.”

The violence continued the next day as the police found themselves overwhelmed by thousands of white rioters who vandalized school buses and set them on fire, burned tires in the street, and smashed store windows. Dozens of people were injured, including children hit in the head with bricks and a police officer who lost an eye.

When I was learning to write, I was taught to ask a series of questions: Who? What? When? Where? Why? and How? The ACE curriculum answers the when (1975) and where (Louisville, Kentucky), but it does not answer any of the other questions. It does not tell students who rioted, what they did, or why they rioted. If a high school student turned in an assignment written like this, it would be sent straight back for revisions.

This section in the ACE text isn’t outdated; it’s in the latest edition, released in 2015. According to their website, ACE curriculum is used by 6,000 schools and “countless” homeschooled students around the world.

Chew on that for a moment.