Christmas According to Dickens

by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts

Copyright © 2011 by Mark D. Roberts and Patheos.com

Note: You may download this resource at no cost, for personal use or for use in a Christian ministry, as long as you are not publishing it for sale. All I ask is that you acknowledge the source of this material: http://www.patheos.com/blogs/markdroberts/.

For all other uses, please contact me at mark@markdroberts.com. Thank you.

Our Favorite Christmas Carol?

If you were to ask people “What is your favorite Christmas carol?” you’d get a wide variety of answers. Many would offer up “Silent Night” or “Joy to the World.” Folks who count all Christmas songs as carols might mention “Winter Wonderland” or “The Christmas Song” (Chestnuts roasting . . .). In fact, these two were the most popular holiday songs in the last decade, according to ASCAP.

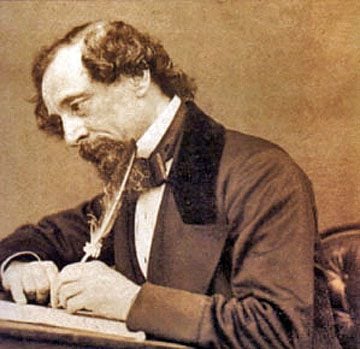

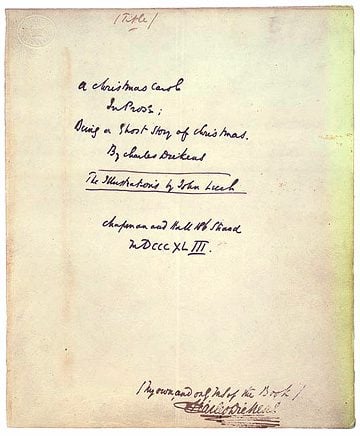

But when I refer to “our favorite Christmas carol,” I’m actually thinking of a different genre altogether. I want to talk about, not holiday hymns and songs, but a book known as A Christmas Carol. Of course, I’m speaking of the holiday classic by Charles Dickens. If you were to add up the sum total of human love for this book, it might just be the most beloved of all Christmas carols. It is surely the most popular of all Christmas stories, save for the one that is found in the pages of the New Testament.

A Christmas Carol Many Times Over

I have read A Christmas Carol probably ten times, ever since I began doing so as a yearly holiday tradition. I have listened to a recorded version of the book about three times. I have watched cinematic renditions of the story at least ten times, ranging from the sublime 1951 version starring Alastair Sim to the ridiculous Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol from 1962. Moreover, I have seen live dramatic presentations of this story at least a dozen times, including the Christianized version that was presented every year at the church where I grew up, as well as the always outstanding performance at the Glendale Centre Theatre (which is still offering its winsome drama, now in its 47th year). In fact, last year I played the role of Marley’s ghost in a shortened dramatic version of A Christmas Carol at my work Christmas party. I hope there was more of grave than gravy in me.

When you add up the numbers, I have read or watched or listened to A Christmas Carol at least thirty five times, and counting. No other work of fiction even comes close to this number in my whole life experience, except, perhaps, for reading Goodnight Moon to my children when they were young. Yet, even after thirty-five exposures, I still love A Christmas Carol. Indeed, I may very well appreciate it more now than ever.

Why Is A Christmas Carol So Beloved?

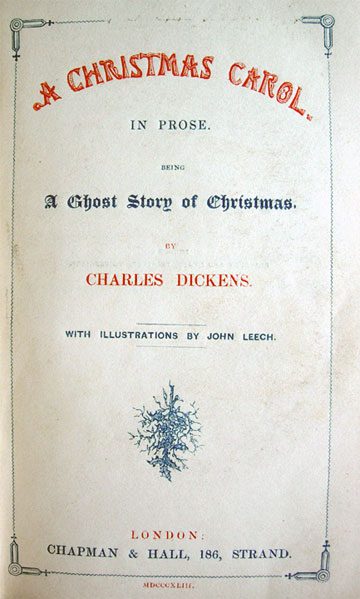

Well, there are several obvious features of A Christmas Carol that augment its easy likability. First of all, it is short. You can read it in less than two hours. When Dickens himself used to do public, oral readings of the book (as he often did), he’d take only three hours or so. In truth, A Christmas Carol really isn’t a novel. It’s more of a novella, or, as Dickens himself labels it, “Ghost Story of Christmas.”

Second, A Christmas Carol is about Christmas, obviously enough. This is a popular subject, even in today’s increasingly secular world. It’s hard to imagine that An Epiphany Carol or even A New Year’s Eve Carol would capture our imaginations as much as A Christmas Carol. Yet, Dickens wrote four other Christmas books that are rarely read. This fact suggests that A Christmas Carol’s popularity has to do with more than just its happy theme.

Third, A Christmas Carol features the literary elements that make Dickens such a delightful author. It’s filled with mouthwatering descriptions of luscious food and drink. It has lots of suspense and lots of humor. The characters are truly memorable, even ones that have very few lines. Who doesn’t remember Tiny Tim and his iconic “God bless us, everyone!”? And, of course, A Christmas Carol is a salient example of Dickens’ inimitable narrative style, a kind of “I’m-your-friend” storytelling that draws the reader into the tale and features utterly enjoyable, ironic, lush descriptions.

All of this contributes to the popularity of A Christmas Carol, to be sure. But none of what I’ve suggested accounts for the unprecedented popularity of Dickens’ little story. This, I believe, results from the narrative core of the story, the changed soul of Ebenezer Scrooge. Above all, we delight in watching an ice-cold, stony heart become warm and tender. As we observe the transformation in Scrooge, we just may feel a bit of it ourselves.

Christmas According to Dickens

Today’s post is the first part of a blog series I’m calling Christmas According to Dickens. Since beginning my blog in December 2003, I have occasionally touched on this topic before. Now it’s time for yet another go. In the days ahead, I’ll give some background on Dickens and the writing of A Christmas Carol, including some truly surprising details that are unknown to most people. Then I’ll move into the center of this series, an exploration of Scrooge’s miraculous transformation. I’ll be seeking to answer the question: Why did Scrooge change? Finally, I’ll offer some thoughts about what you and I can learn from the example of Ebenezer Scrooge.

I’m doing this series partly because I’m fascinated by the subject, and partly because I love A Christmas Carol and admire its author. Dickens is probably my favorite writer, or at least he ranks in the top three. I will be commenting on A Christmas Carol not as a scholar of English literature (which I am not, at any rate), but as a faithful enthusiast and also a Christian theologian. Along the way, I’ll offer some pastoral reflections on the story, touching upon ways that Dickens encourages us in our life of faith. Though he was not an orthodox Christian, Dickens was a believer in God whose work reflected, in many ways, both a Christian worldview and Christian values. So, while we should not derive our theology from Dickens, we can find much in A Christmas Carol to stir our hearts and inspire our actions.

Resources for A Christmas Carol

I’d like to recommend a couple of resources that will augment your appreciation of A Christmas Carol.

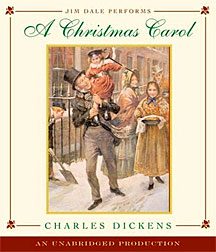

The first is an audio version of the book, performed by Jim Dale. Dale, who is well known for his inspired reading of the Harry Potter series, is a master reader. His interpretation of Dickens brings the story to life. One of my favorite ways of “reading” A Christmas Carol is by listening to Jim Dale.

The first is an audio version of the book, performed by Jim Dale. Dale, who is well known for his inspired reading of the Harry Potter series, is a master reader. His interpretation of Dickens brings the story to life. One of my favorite ways of “reading” A Christmas Carol is by listening to Jim Dale.

The second resource is a book that will help you understand every last word in A Christmas Carol. The Annotated Christmas Carol includes a marvelous introduction and commentary by Michael Patrick Hearn, a distinguished literary scholar. Now you can appreciate the nuances and historical connections Dickens incorporated into the book.

Dickens: The Man Who Invented Christmas?

In 1988, the Sunday Telegraph of London gave Charles Dickens the title of “The Man Who Invented Christmas.” If you’re not familiar with the history of Christmas celebrations, this may seem like an enormous exaggeration. But when you look more closely, the Telegraph’s hyperbole turns out to be closer to the truth than you might expect.

The Context for Writing A Christmas Carol

Of course, Christians had been celebrating the birth of Christ for centuries before Charles Dickens came along. Plus, northern Europeans also had their winter festivals, both pagan and secular. But, in England at the turn of the nineteenth century, Christmas had almost vanished from the scene.

There were several reasons for this disappearance. In part, the continued influence of conservative Reformed Christians – who believed that people should do only what the Bible commands, and therefore should not celebrate Christmas, especially given its popular excesses – meant that for many in England Christmas was not a valid holiday. Now before you’re too tough on my theological forebears, you should know that some of the popular Christmas celebrations in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were a long way from the festive gatherings we associate with this time of year. They were rather like the worst of office parties, rife with drunkenness and sexual license, combined with the hooliganism we see in some extreme celebrations of Halloween. Even many Anglicans were outraged by what they saw. The Reverend Henry Bourne of Newcastle lamented that Christmas was “a pretense for Drunkenness, and Rioting, and Wantonness” (Les Standiford, The Man Who Invented Christmas: How Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol Rescued His Career and Revived Our Holiday Spirits, p. 107. If you want the full story of “the man who invented Christmas,” Standiford’s book is an excellent source.)

Anyway, even though English Christians of a Puritan stripe had actually outlawed Christmas in the 17th century during their brief flirtation with political power, their efforts to wipe out the holiday had been largely unsuccessful. The disappearance of Christmas from English culture had much more to do with the social impact of industrialization and urbanization. As large numbers of people left their ancestral villages to move to the large cities, they also left behind most of their cultural traditions, such as the celebration of Christmas. Moreover, in the cities, bosses weren’t inclined to encourage a holiday that meant a day off from work, especially a day of paid vacation. (Ebenezer Scrooge’s reticence to give Bob Cratchit a holiday on Christmas wasn’t that unusual in his day.)

Another implication of big city life in Victorian England was widespread poverty and human suffering. Although many people worked in factories and offices, wages were low and living conditions poor. This was an abiding concern for Charles Dickens, especially in the fall of 1843. Amid his busy writing career, he was working hard to raise support for institutions that educated and otherwise helped the urban poor of England (not unlike the “portly gentlemen” in Stave I of A Christmas Carol).

In October 1843, a trip to Manchester poured fuel on the flame of Dickens’s passion for the poor. As he spoke at the Athenaeum, an institution devoted to caring for the poor in Manchester, Dickens’s heart was strangely moved. Moreover, he had stayed with his beloved sister Fan (the name of Ebenezer Scrooge’s dear sister in A Christmas Carol), who had two young sons, one of whom was frail and sick (not unlike Tiny Tim). So in October, Dickens began to write A Christmas Carol. According to his own testimony, his writing of this short book was rather a spiritual experience.

The Impact of A Christmas Carol

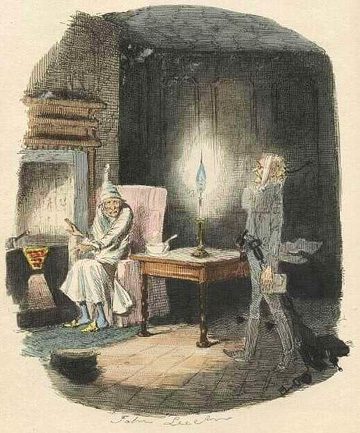

A Christmas Carol was published on December 19, 1843. All 6,000 copies of the first edition were sold in only four days! The book became instantly popular, though the high cost of printing, including the fine illustrations, limited Dickens’s profits. Before long, however, vast numbers of people in England and America knew the story, not only from reading the book, but also from dramatic presentations and many public readings by Dickens himself.

Because our own celebrations of Christmas have been so strongly influenced by Dickens, we can easily overlook his special contributions to our traditions, such as:

• Christmas as a major holiday. At the time of Dickens, it was relatively ignored by most people.

• Christmas as a one (or two) day celebration rather than the traditional twelve.

• Christmas as an occasion for family and close friends to gather for luscious food, singing, dancing, and games. Before A Christmas Carol, turkey was an uncommon on Christmas tables. After the book, it became the meat of choice for this holiday (Standiford, 184-185).

• Christmas as a time for being generous to the poor.

Dickens did not so much invent these traditions as he resurrected them and popularized them. Much of what we assume to be true of Christmas celebrations today derives from the vision of Dickens, especially as portrayed in A Christmas Carol.

So close was the connection between Charles Dickens and Christmas that, when he died in 1870, a young woman who heard of it was aghast. “Dickens dead?” she exclaimed. “Then will Father Christmas die too?” Well, as it turns out, Father Christmas didn’t die along with his greatest promoter, Charles Dickens. The influence of this man, and most of all his masterful novella, A Christmas Carol guaranteed that Christmas would be kept for generations upon generations.

In my next post I’ll focus on one of the essential elements in a Dickens Christmas, something I believe we all should include in our holiday celebrations today.

The Real Business of Christmas, according to Charles Dickens

In yesterday’s post I began to explain the impact of Charles Dickens, especially through A Christmas Carol, upon our celebrations of Christmas. In fact, it’s not too much of an exaggeration to describe him, in the words of the London Sunday Telegraph, as “the man who invented Christmas.”

Dickens’ influence on our Christmas traditions is keenly felt today in many ways, even though we may not be aware of it. In this post I want to offer one salient example that flows from the pages of A Christmas Carol into our lives today.

Business in Stave One of A Christmas Carol

Early in the first stave (chapter), Ebenezer Scrooge receives an unwelcome Christmas Eve visit from his nephew. When his Uncle Scrooge questions the value of Christmas, Fred responds:

“But I am sure I have always thought of Christmas time, when it has come round-apart from the veneration due to its sacred name and origin, if anything belonging to it can be apart from that-as a good time; a kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time; the only time I know of, in the long calendar of the year, when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely, and to think of people below them as if they really were fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys. And therefore, uncle, though it has never put a scrap of gold or silver in my pocket, I believe that it has done me good, and will do me good; and I say, God bless it!”

Even apart from its religious significance, Fred sees Christmas as worthwhile because it is a time of unusual generosity. Of course Scrooge doesn’t buy into this one bit. He dismisses Fred with a series of rude “Good afternoons.”

No sooner had Fred left his uncle alone than “two portly gentlemen, pleasant to behold” drop in on Mr. Scrooge. One explains his business thus:

“At this festive season of the year, Mr. Scrooge,” said the gentleman, taking up a pen, “it is more than usually desirable that we should make some slight provision for the Poor and destitute, who suffer greatly at the present time. Many thousands are in want of common necessaries; hundreds of thousands are in want of common comforts, sir.”

When Scrooge is unmoved, the man explains, “We choose this time, because it is a time, of all others, when Want is keenly felt, and Abundance rejoices.” Of course, Scrooge wants nothing to do with their efforts to make provision for the poor, exclaiming: “It’s not my business. . . . It’s enough for a man to understand his own business, and not to interfere with other people’s.”

But some ghostly interference in Scrooge’s life changes his opinion on the matter of his business, especially at Christmastime. The ghost of Jacob Marley, Scrooge’s former business partner, laments his failure to have lived his life well by caring for others. Scrooge attempts to reassure him by saying, “But you were always a good man of business,” to which the ghost responds:

“Business!” cried the Ghost, wringing its hands again. “Mankind was my business. The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence, were, all, my business. The dealings of my trade were but a drop of water in the comprehensive ocean of my business!”

Then Marley’s ghost adds an extra note about Christmas:

“At this time of the rolling year,” the spectre said, “I suffer most. Why did I walk through crowds of fellow-beings with my eyes turned down, and never raise them to that blessed Star which led the Wise Men to a poor abode? Were there no poor homes to which its light would have conducted me?”

Notice that if Jacob Marley had imitated the Wise Men, he wouldn’t have been led to worship the Christ child, but rather to be generous to the poor. Benevolence, rather than faith, is central to Dickens’s vision of the Christmas.

Business in Stave Five of A Christmas Carol

As Scrooge is visited by Marley and his coterie of ghosts, Scrooge’s heart softens towards all people, especially the poor. Thus, when his transformation is complete in Stave 5, the very first thing Scrooge does is to purchase a giant turkey for the family of his poor clerk, Bob Cratchit. Then, as he is walking about on Christmas morning, he runs into the same portly gentlemen who had the unfortunate experience of meeting Scrooge the previous day. Yet, now, things are quite different. Scrooge approaches them, offers them Christmas greetings, and then whispers something in the ear of one of the men, presumably revealing how much he will contribute to their effort to help the poor. Here’s the following dialogue:

“Lord bless me!” cried the gentleman, as if his breath were taken away. “My dear Mr. Scrooge, are you serious?”

“If you please,” said Scrooge. “Not a farthing less. A great many back-payments are included in it, I assure you. Will you do me that favour?”

“My dear sir,” said the other, shaking hands with him. “I don’t know what to say to such munificence-”

“Don’t say anything please,” retorted Scrooge. “Come and see me. Will you come and see me?”

The primary and most obvious proof of Scrooge’s transformation in the end of A Christmas Carol is not simply his delight in Christmas, nor his attendance at church, nor even his joining his nephew’s Christmas party. Rather, the proof that Scrooge is a changed man is seen in his exceptional generosity, both with the Cratchit family in particular and with all needy people in general.

So when Dickens concludes that Scrooge “knew how to keep Christmas well,” he means more than that he abolished “Bah! Humbug!” in favor of “Merry Christmas!” Ebenezer Scrooge kept Christmas well by becoming “as good a man, as the good old city knew, or any other good old city, town, or borough, in the good old world.” This goodness is seen especially in his generosity, both at Christmas and throughout the year. He learned the truth that had eluded Jacob Marley in this life, namely: “Mankind was my business. The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence, were, all, my business.” These became the business of Ebenezer Scrooge, even as they should be central to the business of Christmas.

A Further Reflection

Before I stop, I would at least like to mention an obvious tension between the vision of Dickens and that of contemporary American culture. For us, Christmas is a time of business, the business of buying and selling. We hear again and again how important the Christmas season is for business. News stories about shopping abound: Black Friday, Cyber Monday, crowds in the malls, comparisons between this year and last year, predictions by economists, etc. etc. If we are going to celebrate Christmas in the secular mode of Dickens, don’t you think we’d all be better off by focusing on what Dickens considered the real business of Christmas, the business of caring for those in need, the business of giving to others, the business of generous living?

A Way to Do the “Real Business” of Christmas

![]() You may very well have a favorite charity you support at Christmastime, or you may want to give a special gift to your church. That’s great. But if you are looking for a way to share in the “real business” of Christmas, may I recommend World Vision. Their website makes it very easy for your to give a wide variety of amounts for a wide variety of causes. Personally, I choose to support the “Maximum Impact Fund.” But there are many other options. In just a couple of minutes, you could do the business of Christmas.

You may very well have a favorite charity you support at Christmastime, or you may want to give a special gift to your church. That’s great. But if you are looking for a way to share in the “real business” of Christmas, may I recommend World Vision. Their website makes it very easy for your to give a wide variety of amounts for a wide variety of causes. Personally, I choose to support the “Maximum Impact Fund.” But there are many other options. In just a couple of minutes, you could do the business of Christmas.

The First “Ebenezer Scrooge”

If I were to tell you that Charles Dickens wrote a story about a solitary, crotchety old man who despised both people and Christmas until some supernatural visitors came to him on Christmas Eve and taught him to have a new perspective on life, you’d probably say, “Yes, of course, Ebenezer Scrooge.” But if I were to tell you I wasn’t thinking of Ebenezer Scrooge at all, but rather of Gabriel Grub, you might be a bit surprised. So go ahead and be surprised, if you wish, because what I’m saying is true.

Introducing Gabriel Grub, the First “Scrooge”

In 1836, seven years before he wrote A Christmas Carol, Dickens published a short story as Chapter 29 of The Pickwick Papers. “The Story of the Goblins who stole a Sexton” relates the strange experiences of Gabriel Grub, the sexton (caretaker and gravedigger) for a church in a rural village, and a literary cousin of Ebenezer Scrooge. According to Dickens, Gabriel Grub was “an ill-conditioned, cross-grained, surly fellow – a morose and lonely man, who consorted with nobody but himself.” He had “a deep scowl of malice and ill-humor.” Sounds like Scrooge, doesn’t he?

One Christmas Eve, Grub decided to go to the churchyard to dig a grave. As he walked through the streets of his village, he watched people making preparations for Christmas parties – parties he wouldn’t even think to attend, should he have been invited. When he saw children playing games, Grub amused himself with the thought of “measles, scarlet fever, thrush, whooping-cough, and a good many other sources of consolations besides.” If his neighbors offered him a Christmas greeting, Grub returned “a short, sullen growl,” not “Humbug!” but its pre-verbal precursor. When a young lad was singing a Christmas song in the street, Gabriel Grub cornered the boy and “rapped him over the head with his lantern five or six times.” As he began digging a grave, Grub cheered himself with this thought: “A coffin at Christmas! A Christmas box! Ho! ho! ho!”

But then, Gabriel Grub received a surprise visitor, a grinning goblin who taunted him with clever dialogue. Soon this goblin was joined by “a whole troop of goblins” who captured Grub and dragged him down into the earth. Grub found himself in a cavern with the first goblin, the “king of goblins,” and his band. They proceeded to show him a series of scenes that were magically projected in the end of the cavern. The first scene was of a poor family: many children and their mother. The children rejoiced when their father joined them. But then the scene shifted to a bedroom, in which “the fairest and youngest child lay dying.” “Even as the sexton looked upon him with an interest he had never felt or known before, the little boy died.” Yet the family had assurance that their little one was in “happy Heaven.” (The similarity between this scene and that of Bob Cratchit’s family in A Christmas Carol is striking.)

After the magic scene ended, the goblins beat Gabriel Grub, and then showed him another ghostly video. This sequence of viewings and beatings happened many times over, and “many a lesson it taught to Gabriel Grub.” “He saw that men who worked hard, and earned their scanty bread with lives of labour, were cheerful and happy . . . because they bore within their own bosoms the materials of happiness, contentment, and peace.” On the other hand, Gabriel Grub “saw that men like himself, who snarled at the mirth and cheerfulness of others, were the foulest weeds on the fair surface of the earth, and setting all the good of the world against the evil, he came to the conclusion that it was a very decent and respectable sort of world after all.” At this point he fell asleep, only to awake in the churchyard on Christmas morning.

After his encounter with the goblins, Grub “was an altered man.” Yet “he could not bear the thought of returning to a place where his repentance would be scoffed at, and his reformation disbelieved.” So, Gabriel Grub disappeared from his village for ten years. When he finally returned, he was “a ragged, contented, rheumatic old man.” The moral of the story, according to the narrator, was “that if a man turn sulky and drink by himself at Christmas time, he may make up his mind to be not a bit the better for it: let the spirits be never so good.”

Gabriel Grub and Ebenezer Scrooge

Reading the story of Gabriel Grub is like looking at the charcoal sketches of an artist getting ready to paint a masterpiece. The parallels between “The Story of the Goblins” and A Christmas Carol are obvious: a solitary, nasty old man not only refuses to celebrate Christmas, but also spurns the greetings of those who do, and even tries to hurt a boy who sings a Christmas carol. On Christmas Eve, this man receives unexpected supernatural visitors who proceed to show him many scenes of life, including a moving scene of a poor, loving family whose youngest child is terribly ill. In the end, the man is changed by this experience. These are some of the obvious parallels between the story of Gabriel Grub and that of Ebenezer Scrooge.

Of course there are also many differences between “The Story of the Goblins” and A Christmas Carol. One of the most striking differences emerges when we compare conclusions. Whereas Gabriel Grub slunk away out of fear that the townspeople would laugh at him, Ebenezer Scrooge resolved to live a changed life. After the Ghost of Christmas Future revealed to Scrooge his own sorry death, Scrooge exclaimed: “I will honour Christmas in my heart, and try to keep it all the year. I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future. The Spirits of all Three shall strive within me. I will not shut out the lessons that they teach.” And so he did.

Yet, in light of the tale of Gabriel Grub, who ran away from town for fear of people’s laughing scorn, let’s read once again from the conclusion to A Christmas Carol. Scrooge had just promised to Bob Cratchit that he would raise his salary and help his struggling family. After this Dickens writes:

Scrooge was better than his word. He did it all, and infinitely more; and to Tiny Tim, who did not die, he was a second father. He became as good a friend, as good a master, and as good a man, as the good old city knew, or any other good old city, town, or borough, in the good old world. Some people laughed to see the alteration in him, but he let them laugh, and little heeded them; for he was wise enough to know that nothing ever happened on this globe, for good, at which some people did not have their fill of laughter in the outset; and knowing that such as these would be blind anyway, he thought it quite as well that they should wrinkle up their eyes in grins, as have the malady in less attractive forms. His own heart laughed: and that was quite enough for him. (emphasis added)

Both in “The Story of the Goblins Who Stole a Sexton” and in A Christmas Carol, Dickens recognizes that people will laugh when a person is transformed from bad to good. Yet, whereas fear of this response kept Gabriel Grub in bondage, Scrooge was able to transcend it. “His own heart laughed: and that was quite enough for him.” Just as Gabriel Grub recognized that people must have happiness in their hearts, and that this helps them overcome life’s difficulties, so it was with Ebenezer Scrooge.

But the differences between Grub and Scrooge suggest a tantalizing question: Why did Ebenezer Scrooge change? And why did he change so thoroughly that he didn’t even mind if people were to laugh at him? To these questions I’ll return in my next post in this series.

“Ebenezer Scrooge” – The Meaning of the Name

As a first step in our consideration of the question “Why did Ebenezer Scrooge change?” I want to examine the character’s name. Charles Dickens was an author who paid attention to the tiniest details of a story. Surely he chose the name “Ebenezer Scrooge” quite intentionally, fully aware of its multiple layers of meaning.

The Meaning of “Scrooge”

For us, the word “Scrooge” is synonymous with “cranky, selfish miser.” The character of Ebenezer Scrooge is so familiar that if you were to refer to someone as a “Scrooge,” just about everybody in the Western world would know what you mean. They’d understand that you were not offering a compliment!

For us, the word “Scrooge” is synonymous with “cranky, selfish miser.” The character of Ebenezer Scrooge is so familiar that if you were to refer to someone as a “Scrooge,” just about everybody in the Western world would know what you mean. They’d understand that you were not offering a compliment!

In fact, however, the name “Scrooge” is a variation of an obscure English verb: “to scrouge” or “to scruze.” This verb means “to squeeze” or “to press.” The fact that Dickens chose the name “Scrooge” with this meaning in mind is clear in the classic description of the character in Stave One of A Christmas Carol:

Oh! But he was a tight-fisted hand at the grind-stone, Scrooge! a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous, old sinner! Hard and sharp as flint, from which no steel had ever struck out generous fire; secret, and self-contained, and solitary as an oyster. The cold within him froze his old features, nipped his pointed nose, shrivelled his cheek, stiffened his gait; made his eyes red, his thin lips blue; and spoke out shrewdly in his grating voice. A frosty rime was on his head, and on his eyebrows, and his wiry chin. He carried his own low temperature always about with him; he iced his office in the dog-days; and didn’t thaw it one degree at Christmas.

It’s as if Dickens opened his thesaurus and copied down every synonym of “squeezing.”

What did Ebenezer Scrooge squeeze so tightly? Most obviously, he squeezed his money. He grasped it and clung to it. He held it so tightly that he was unwilling to part with a farthing. But Ebenezer Scrooge also squeezed his heart. He suffocated his own soul with his obsession with gain. Greed was choking the life out of Ebenezer Scrooge.

I believe without a doubt that Dickens chose the name “Scrooge” primarily because of its underlying meaning. But I wonder if a couple other factors figured into the naming equations. First, I wonder if Dickens chose a name that was uncommon or unique. If you’re going to produce a character who is a classic miser, you may not want to name him “Mr. Smith” or “Mr. Roberts,” out of deference to those who have these surnames. Second, the word “Scrooge” just begs to be spoken in a slow, resonant, ghostly manner. When Marley’s ghost drones “Scroooooooge,” that works much better, for example, than “Craaaaachit.” I wouldn’t be surprised if Dickens chose “Scrooge” for its sound as well as its meaning.

The Meaning of “Ebenezer”

In English, Ebenezer is a man’s name. Today it is quite uncommon, apart from its association with A Christmas Carol. In the time of Charles Dickens, men were called Ebenezer, though I’m not able to judge how common the name was. So, for example, in 1840, three years before Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol, a man named Ebenezer Elliott, who identified himself as a “Corn-Law Rhymer,” published a book of his poetical works (Edinburgh: William Tait, 1840).

The name “Ebenezer” is not original to the English language. In fact, itis an anglicized version of a Hebrew name, which is itself composed of two Hebrew words. In 1 Samuel 4:1, for example, the Israelities camped at a place called Ebenezer. This name is a combination of the Hebrew word for stone (eben) and the Hebrew word for helper (‘ezer). Thus, an ebenezer (literally, ha-eben ha-’ezer) would have been a stone that offered some sort of assistance. In 1 Samuel 7:12, the judge Samuel sets up a stone as a monument in remembrance of God’s special help. It was a “help-stone” that reminded the Israelites of God’s care. It was rather like those little monuments you find along highways throughout the United States. They commemorate some event long past, helping us to remember what we would otherwise forget.

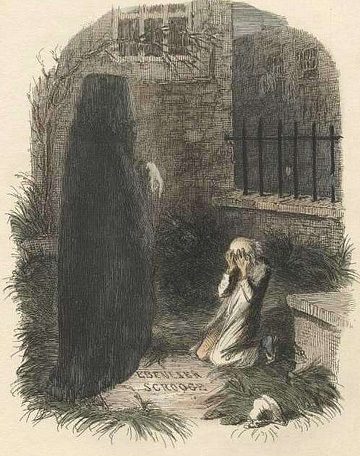

Interestingly enough, the name “Ebenezer” appears rarely in A Christmas Carol. Scrooge’s first name is not mentioned in the first pages of the book. We don’t hear it until Marley’s ghost speaks the name, first in explaining that he has no comfort to offer his former partner. Marley’s second use of “Ebenezer” comes when he explains the purpose of his visit: “I am here to-night to warn you, that you have yet a chance and hope of escaping my fate. A chance and hope of my procuring, Ebenezer.” This is the first instance of grace given to Scrooge, and he receives it with his first communication of gratitude, saying, “You were always a good friend to me. . . . Thank ‘ee!” The only other character to use the name “Ebenezer” is Old Fezziwig, Scrooge’s former employer whom Scrooge holds in high esteem. The final use of “Ebenezer” in A Christmas Carol comes on a literal ebenezer, Scrooge’s gravestone. This stone completes the transformation of Scrooge, showing him of how his life might end if he does not become a new man.

Charles Dickens, though not orthodox in his Christian faith, was certainly familiar enough with the Bible to have known the meaning of the name Ebenezer. Given this knowledge and his attention to character names, it seems to me likely that he chose the name “Ebenezer” quite intentionally. Ebenezer Scrooge was not only a man with a “squeezing, wrenching, grasping” character. He was also to serve as a monument for readers of A Christmas Carol. Dickens intended Ebenezer Scrooge to remind us of things we ought not forget, lest we end up like Jacob Marley and the other spirits who walked the earth in sorrow, dragging the heavy chains they forged in life.

What Does Scrooge Remind Us Of?

Ebenezer Scrooge reminds us of several things. First and most obviously, he reminds us of Christmas. One cannot read A Christmas Carol without renewing one’s excitement for this unique holiday. As I have noted earlier in this series, when Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol, Christmas was by no means a major or beloved holiday. Dickens used the “help-stone” of Ebenezer Scrooge to promote the importance of Christmas.

But for Dickens, the principal value of Christmas was not to celebrate the birth of the Son of God into the world. Rather, Christmas was a time for enjoying friends and family. Moreover, and most of all, it was an occasion for generosity. Dickens’ own estimation of Christmas appears in Stave One on the lips of Scrooge’s nephew, Fred, who says:

But I am sure I have always thought of Christmas time, when it has come round–apart from the veneration due to its sacred name and origin, if anything belonging to it can be apart from that–as a good time; a kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time; the only time I know of, in the long calendar of the year, when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely, and to think of people below them as if they really were fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys.

As the story of A Christmas Carol plays out, this theme is emphasized time and again. Thus, for Dickens, Ebenezer Scrooge is an ebenezer who reminds us, not only to celebrate Christmas, but also to do so through being generous to the poor, especially to poor children.

What Made Scrooge Scrooge?

If you call somebody a Scrooge today, everybody will know what you mean. You’re implying that someone is miserly, grumpy, and selfish, especially but not only during Christmastime.

Soon I want to examine what made Ebenezer Scrooge change from being, well, Scrooge, to being a generous man who loved both people and Christmas. But before I get to this, I want to consider what turned the human being named Ebenezer Scrooge into the archetypal mean-spirited miser.

I realize this question is more of a 21st-century question than a 19th-century question. It’s only been in the last century that we’ve become fascinated, one might say, obsessed by psychological causes of behavior. Yet, even though Charles Dickens didn’t supply a lengthy biography of Scrooge, we can nevertheless discover some of what made him the man he became. This knowledge may also help us to understand what unmade and remade him.

Scrooge’s Difficult Childhood

Most of what formed the soul of Ebenezer Scrooge appears in Stave 2 of A Christmas Carol, when the Ghost of Christmas Past shows Scrooge images of his past experiences. Our very first view of the younger Scrooge comes as he sits alone in his boarding school on Christmas Eve. He is “a solitary child, neglected by his friends.” Seeing his young, abandoned self, the grown up Scrooge sobs with a peculiar kind of empathy. The only joy in this lonely boy’s life comes from fantasy books.

The next scene from Scrooge’s past begins, once again, when he is abandoned by the other boys who had gone home for Christmas. But this time Ebenezer receives a surprise visit from his sister, Fan. She brings the good news that Ebenezer will be coming home for Christmas, and even beyond that. Here’s a bit of the dialogue:

‘Home, little Fan?’ returned the boy.

‘Yes!’ said the child, brimful of glee. ‘Home, for good and all. Home, for ever and ever. Father is so much kinder than he used to be, that home’s like Heaven! He spoke so gently to me one dear night when I was going to bed, that I was not afraid to ask him once more if you might come home; and he said Yes, you should; and sent me in a coach to bring you. And you’re to be a man!’ said the child, opening her eyes,’and are never to come back here; but first, we’re to be together all the Christmas long, and have the merriest time in all the world.’

In this short paragraph, we learn some crucial facts about Ebenezer Scrooge’s sorry childhood:

• He had been sent away from home to a boarding school.

• His father used to be cruel.

• He had previously been left alone at school for Christmas.

• His mother was dead (implied, since she isn’t mentioned at all).

These bits of data begin to explain why Scrooge became Scrooge. But the next scene in Scrooge’s past shows that he hadn’t been completely corrupted by his difficult childhood. In this scene, he is serving as an apprentice for a fun-loving, generous man named Fezziwig. Ebenezer appears to have thrived under Fezziwig’s tutelage, and also been close to his fellow apprentice, Dick Wilkins. We have no hint of the selfish, Christmas-hating man whom Scrooge became.

Scrooge’s Young Adulthood

Yet something happened after Scrooge’s apprenticeship under Fezziwig that changed his heart for the worse. We learn about this from the next scene in Scrooge’s past. There, his fiancée informs Ebenezer that she is to break their engagement. Why? Because “another idol has displaced me,” she explains. And this idol is “a golden one,” which Dickens calls “Gain” and we would call “Greed.” The dialogue continues:

[Scrooge says,] “There is nothing on which [the world] is so hard as poverty; and there is nothing it professes to condemn with such severity as the pursuit of wealth!”

“You fear the world too much,” she answered, gently. “All your other hopes have merged into the hope of being beyond the chance of its sordid reproach. I have seen your nobler aspirations fall off one by one, until the master-passion, Gain, engrosses you. Have I not?”

Scrooge has become the tight-fisted, hard-as-nails man who cares only about financial gain. What has driven him to this? Partly, it’s his recognition of how difficult poverty is. This came for Scrooge, as it did for Charles Dickens, from his own bitter experience. And it has led him to be consumed, not just by materialism, but also by fear. He is so afraid of poverty’s lash that he has abandoned his “nobler aspirations,” including the desire to marry the woman he loves and who had once loved him.

No doubt the rejection Scrooge experienced from his fiancée hardened his heart still further. Love itself was to be scorned, which is exactly what Scrooge had done in the Stave 1, when his nephew admitted to marrying because he fell in love: “‘Because you fell in love!’ growled Scrooge, as if that were the only one thing in the world more ridiculous than a merry Christmas.”

The hard-hearted, grasping Scrooge found strength and solace in the social philosophy of his day, which thought of the poor as deserving their sorry fate and even as being a threat to the well-being of the world. When, in Stave 1, Scrooge rejects the request of the two “portly gentlemen” for a charitable gift for the poor, he suggests that the poor might die “and decrease the surplus population.” Here Scrooge echoes the views of the influential economist Thomas Malthus, whose theories would have allowed a man like Scrooge to defend his greed and lack of compassion for the poor.

What Made Scrooge Scrooge?

So, what made Scrooge Scrooge? You start with an unhappy childhood: mother dead; cruel father; sent away from home to overly strict boarding schools; no friends among classmates; only solace in books; the only student not going home for Christmas. Then you throw in a strong fear of poverty along with a growing love for the safety represented by material gain. Add the rejection of a fiancée. And top it off with popular philosophy that praises acquisitiveness and derides the poor as deserving of their condition. What have you got? Scrooge! Scrooge: whose heart has been squeezed by the impact of a sorry life and his own sorry choices. Scrooge: who squeezes his hand around the only thing that gives him meaning and security in life . . . money.

So if this explains, at least in part, how Scrooge became Scrooge, now the question is: What caused Scrooge to change? To this question I will turn in my next post in this series.

Why Did Ebenezer Scrooge Change? Stave I

As A Christmas Carol begins, Ebenezer Scrooge is one of the most unlikable characters in all of literature. Here, once again, is the full version of Charles Dickens’s classic description:

Oh! But he was a tight-fisted hand at the grindstone, Scrooge. a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner! Hard and sharp as flint, from which no steel had ever struck out generous fire; secret, and self-contained, and solitary as an oyster. The cold within him froze his old features, nipped his pointed nose, shrivelled his cheek, stiffened his gait; made his eyes red, his thin lips blue; and spoke out shrewdly in his grating voice. A frosty rime was on his head, and on his eyebrows, and his wiry chin. He carried his own low temperature always about with him; he iced his office in the dog-days; and didn’t thaw it one degree at Christmas.

Don’t you love that description? Now there’s a man in need of an attitude adjustment, or, indeed, a life adjustment. And that’s exactly what happened to Ebenezer Scrooge . . . in less than 100 pages! By the end of the story, here’s the new Scrooge:

Scrooge was better than his word [to Bob Cratchit concerning help for his family]. He did it all, and infinitely more; and to Tiny Tim, who did not die, he was a second father. He became as good a friend, as good a master, and as good a man, as the good old city knew, or any other good old city, town, or borough, in the good old world. . . . [A]nd it was always said of him, that he knew how to keep Christmas well, if any man alive possessed the knowledge.

What in the world can explain such a transformation? Why was Scrooge able to change? How did it happen?

We might begin by saying that nothing in this world can account for the transformation of Ebenezer Scrooge. He needed, and indeed, received supernatural assistance. The change in Scrooge is a direct result of the impact of four ghosts upon him, the spirit of his departed colleague Jacob Marley and the spirits of Christmas past, present, and future. The metamorphosis of a man like Ebenezer Scrooge requires other-worldly influence. In this regard, Ebenezer Scrooge is like his literary forefather Gabriel Grub (see my post from a couple of days ago, “The First Ebenezer Scrooge”), though Scrooge was haunted by ghosts rather than goblins. And, unlike poor Grub, Scrooge didn’t get physically pummeled into submission. The ghosts worked on Scrooge’s heart, not his body.

It wasn’t the mere fact of ghostly visitors that changed Scrooge, however, as if he were scared into repentance. Rather, it was what he experienced with the spirits that made all the difference. Indeed, the ghosts weren’t really necessary for Scrooge’s transformation. It could have all been just a dream with the same result, although would have been much less fun.

The Impact of the Spirit of Jacob Marley

Before Scrooge is visited by Jacob Marley, he shows not the slightest bit of kindness or tenderness. His heart is hard. His focus is utterly self-centered. He has nothing to offer others but scorn and an occasional “Humbug!” In his interaction with Marley’s ghost, however, Scrooge first shows the tiniest morsel of positive feeling to anyone.

When the ghost of Jacob Marley visits Scrooge, at first he doubts the veracity of his visitor. In one of my favorite lines from A Christmas Carol, Scrooge argues that his vision is probably “an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of an underdone potato. There’s more of gravy than of grave about you, whatever you are!” Yet with loud cries and a horrifying change of appearance, Marley’s ghost prevails upon Scrooge’s good sense. He finally believes that the ghost is real.

Scrooge’s first response to this recognition is fear and trembling. His fear grows when he learns that he is destined to wear even heavier post-mortem chains than the onerous ones that Marley himself is forced to carry. “Speak comfort to me, Jacob,” Scrooge begs, in his first real demonstration of some sort of human vulnerability. Yet Marley can offer no real comfort.

Here we catch a glimpse of a speck of tenderness in Ebenezer Scrooge, though it is completely self-centered. He desires comfort because he is terrified to learn about the Hell that awaits him after death. Thus, the frozen heart of Scrooge begins to thaw just a smidgen, even if his feeling is utterly egocentric.

As Marley continues, he explains that he has come to warn Scrooge so that he might escape Marley’s dire fate, “a chance and hope of my procuring, Ebenezer.” To this Scrooge responds, “You were always a good friend to me, . . . Thank’ee.” Here is the first bit of tenderheartedness directed by Scrooge to someone other than himself. He feels gratitude to Marley.

What begins to thaw the frosty heart of Ebenezer Scrooge? It’s the fact that Marley has acted to help Scrooge. It’s Marley’s gift of undeserved kindness that first touches Scrooge’s soul.

Theological Reflections

Undeserved kindness. Theologians call this grace. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that Marley extended grace to his former partner. In no way did Marley owe Scrooge anything. And there’s no reason to believe that Marley stood to gain anything for himself in helping Scrooge, other than, perhaps, the sense of having made a positive difference in Scrooge’s life (and afterlife). Moreover, in no way whatsoever had Scrooge done anything to deserve Marley’s help. Marley’s intervention was simply an act of grace. In fact, it was a demonstration of what theologians call prevenient grace.

Prevenient grace is, simply, grace that comes before anything we do. Prevenient grace takes the initiative. It gets the ball of transformation rolling. The fact that God’s grace is prevenient makes all the difference in the world. It means that we cannot do anything to earn God’s favor, nor must we. It means that God’s favor is given first, and everything we do for good is in some measure a response to that prevenient grace.

Although Dickens was not an enthusiastic Christian – his own faith seemed to be more of a romantic, deistic, Unitarian variety – his anthropology bore much in common with his evangelical contemporaries (of whom he was not particularly fond). According to both Dickens and the evangelicals, human transformation comes as a result of grace, grace that is communicated through a supernatural agent. Of course, in the Christian case, grace comes from God, not a human ghost, and is delivered through the Holy Spirit, not the spirit of a dead colleague. Jacob Marley doesn’t appear in Scripture when I last checked. So when it comes to theology, A Christmas Carol isn’t especially Christian. But Dickens’ understanding of human nature is surprisingly similar to the Christian perspective in some ways. We change in response to grace, with the help of a supernatural spirit.

Though Scrooge’s initial experience of grace softens his stony heart just a bit, it hardly transforms it. This arduous task remains for the spirits of Christmas past, present, and future. To their work I’ll return in my next post in this series.

Why Did Ebenezer Scrooge Change? Stave II

In my last post, I began to examine A Christmas Carol to discover why Ebenezer Scrooge changed so dramatically. I showed that we see the tiniest hint of his transformation in his interaction with the ghost of Jacob Marley, whose graciousness to Scrooge elicited a morsel of gratitude from the old miser. Yet Marley’s impact would be most keenly felt, not in his visit, but in his sending three other spirits to “haunt” Scrooge.

The Impact of the Ghost of Christmas Past

The Ghost of Christmas Past is a strange apparition who explains the purpose of his visit as Scrooge’s “welfare,” or, indeed, his “reclamation.” This process begins with an easily overlooked but crucial interchange between Scrooge and the Spirit. When the Spirit clasps Scrooge’s arm and begins to lead him towards the window, Scrooge resists, saying, “I am a mortal, and liable to fall.” Notice carefully the spirit’s response: “‘Bear but a touch of my hand there,’ said the Spirit, laying it upon his heart, ‘and you shall be upheld in more than this!’” The Spirit touches, not just Scrooge’s arm, but also his heart. And Scrooge would be upheld, not only in his supernatural travels, but also in the opening of his tightly-shut heart.

Then the Spirit magically transports Scrooge to the place where he spent his boyhood. The sights and sounds of his youth begin to soften Scrooge’s heart. Yet the Spirit has only started his transforming effort. Next Scrooge sees his fellow students merrily on their way to celebrate Christmas. The school is deserted, all except for one boy, “a solitary child, neglected by his friends.” It is Scrooge, of course, left alone with nothing to cheer him but the characters from his beloved books. The old man weeps bitter tears for the child he once was. For the first time in a long time, he feels compassion for someone else, even if that “someone else” is really just an earlier version of himself. Yet, as he feels for himself as a boy, Scrooge also shows the first glimmer of care for another human being as well: “There was a boy singing a Christmas Carol at my door last night,” he explains to the ghost. “I should like to have given him something.” Ironically, Scrooge had almost given that boy something – a rap with his ruler!

On some Christmas Eve following the time of his isolation in the school, the young Scrooge receives a visit from Fan, his beloved sister. (Dickens himself had a sister named Fanny.) Fan informs Ebenezer that he can come home for Christmas. (Years later, Fan dies, leaving behind a child-the nephew Fred whom Scrooge had so badly mistreated only hours before.)

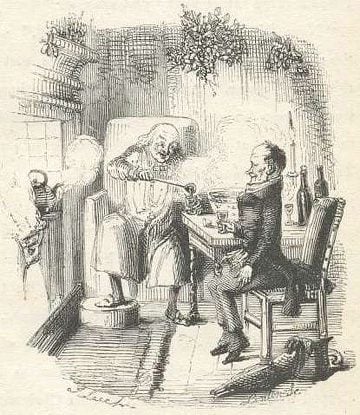

After this tender family scene, the Ghost of Christmas Past takes Scrooge to the warehouse of Old Fezziwig, to whom Scrooge had once been apprenticed. The mere sight of his generous old master brings joy to Scrooge’s heart. Then, as he witnesses a grand Christmas party, “Scrooge had acted like a man out of his wits. His heart and soul were in the scene. . . .” When the Ghost challenges Fezziwig’s actions, Scrooge defends his generosity. And, once again, this begins to be translated into a desire to be generous in his own life: “I should like to be able to say a word or two to my clerk just now,” Scrooge says.

The next scene is not a happy one for Scrooge. He watches as his fiancée, Belle, breaks their engagement, recognizing that Ebenezer loves money far more than he loves her. Then the Ghost shows Scrooge one more scene, in which a Belle is much older, with a husband and daughter. Their family love stands in stark contrast to Scrooge’s own miserly loneliness. At this, Scrooge begs to be removed. “I cannot bear it!” he exclaims.

How Do the Events of Stave II Transform Scrooge?

How does all of this help to transform the heart of Ebenezer Scrooge? His journey starts at a most curious place, with Scrooge looking upon himself as a lonely child. It’s as if Dickens realizes that even hard-hearted people might have the tiniest soft spot for themselves and their own suffering. One might almost be tempted to say that Scrooge is acting out a sort of psychological Golden Rule, loving himself so that he might love others as well. From a psychotherapeutic angle, Scrooge is getting in touch with his inner child.

The vision of the Fezziwigs’ party not only lures Scrooge into a bit of vicarious celebration, but also forces him to reexamine his own values. Mr. Fezziwig, whom the old Scrooge continues to hold in high regard, saw fit to spend a bit of money for the sake of others. “The happiness he gives,” Scrooge insists, “is quite as great as if it cost a fortune.” There’s more to life than money, the old miser begins to realize for the first time in a long time.

The Ghost of Christmas past, beyond conjuring up within Scrooge feelings of nostalgia and celebration, helps him see – and feel – the harsh contrast between love and loneliness. Love figures prominently in his boyhood encounter with his sister Fan. Remembering her love for him – and his for her – makes Scrooge’s grouchy rejection of Fan’s son Fred all the more grievous. Moreover, the scenes featuring Belle press into Scrooge’s heart the lack of love in his own life. Where Scrooge had once felt genuine love (from and for Fan, from and for Belle), he had chosen to cut himself off from this love, whether with his former fiancée, or with Fred. He realizes he has made poor choices for his life, and he starts to wish for something better.

It’s interesting to me that Scrooge doesn’t reject all of this as a bunch of maudlin nonsense. What, I wonder, gives him the ability to see, really to see, his life as it truly was? And what gives him the ability to feel emotions that had for so long been absent from his heart? Yes, seeing himself as a hurting young boy might very well have opened Scrooge’s heart a bit. But this might not have happened were in not for the earlier intervention of the Spirit, when he touched Scrooge’s heart and promised that he would be “upheld” in more than just their other-worldly travel.

Theological Reflections

What can transform a stony heart? For Charles Dickens, the answer has several layers. Nostalgia for the past seems to help. Looking afresh at one’s life makes a difference. Supernatural assistance contributes. But, at the core, love changes people. Love, not of the romantic sort, but of the compassionate, self-giving variety, transforms hearts. When Scrooge witnesses the love of his sister Fan and his master Fezziwig, something happens inside of him. And when he sees how he spurned the love of his former fiancée and how happy she is with a loving husband and daughter, Scrooge realizes how much he has lost be shutting his heart to love.

Here, once again, Dickens’s anthropology is virtually Christian. Christians believe that ultimate transformation in life comes as we experience God’s love for us given through Jesus Christ. Over a century before Charles Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol, another Englishman had something to say about the power of love to transform one’s life. Consider how these words of hymn writer Isaac Watts express something like what happened to Ebenezer Scrooge:

When I survey the wondrous cross On which the Prince of glory died, My richest gain I count but loss, And pour contempt on all my pride. . . .

Were the whole realm of nature mine, That were a present far too small; Love so amazing, so divine, Demands my soul, my life, my all.

For the Christian, the deepest and most transforming kind of love is celebrated, not at Christmas, but on Good Friday. Christmas is what makes Good Friday possible, as the Son of God chooses to love by enduring the cross.

Why Did Ebenezer Scrooge Change? Stave III

When we last left Ebenezer Scrooge, he had just finished being visited by the first of three Christmas Spirits, the Ghost of Christmas Past. He fell into bed, exhausted. At the beginning of Stave III, Scrooge awakes, ready for the visit of the next of the three Spirits. This visitor is the Ghost of Christmas Present, a giant being who exudes the extravagant joy of Christmas (picture Hagrid in a Santa Suit having just eaten way too many Christmas cookies). Though at first hesitant to look at this Spirit, soon Scrooge shows how his heart has begun to change: “Spirit,” said Scrooge submissively, “conduct me where you will. I went forth last night on compulsion, and I learnt a lesson which is working now. To-night, if you have aught to teach me, let me profit by it.”

Like his older brother, the Ghost of Christmas Present shows Ebenezer Scrooge many scenes of Christmas. Here Dickens is at his “Dickensiest” in lavish descriptions of food and festivity, all of which accentuate the joyfulness of Christmas. At first an observer of such delights, in time Scrooge begins to participate in the Christmas games as if he were actually present in the celebrations. He does this most of all as he watches the Christmas party of his nephew, Fred, who, in spite of having been mistreated by his uncle the day before, nevertheless wishes Scrooge a Merry Christmas in absentia.

What has turned Scrooge into a man who delights in Christmas parties? His observation of genuine celebration leads, it seems, to an openhearted desire to become an enthusiastic celebrator. Dickens believes that festivity, especially of the pure-hearted variety, is contagious.

The Impact of the Crachit Family

Yet, what touches Scrooge’s heart in Stave III isn’t merely his looking upon numerous Christmas parties. One scene in particular has special impact upon his soul. It comes as he observes the family of his clerk, Bob Cratchit. Though this family has little in the way of money, they abound in love and joy. The center of their passion is Tiny Tim, the Cratchit’s sickly little boy, who walked with a crutch and was supported by “an iron frame.” This sweet boy may have a crippled body, but his heart is bigger and stronger than most. He’s the one, after all, who offers the generous wish: “God bless us every one!”

Viewing Tiny Tim in his weakened state, Scrooge asks the Spirit “if Tiny Tim will live.”

“If these shadows remain unaltered by the Future,” the Spirit responds, “the child will die.”

“No, no,” said Scrooge. “Oh no, kind Spirit! say he will be spared.”

To which the Spirit quotes Scrooges own words from Stave 1: “If he be like to die, he had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.” Confronted in this way, “Scrooge hung his head to hear his own words quoted by the Spirit, and was overcome with penitence and grief.”

Precisely at this point in the story, Bob Cratchit offers a toast to Mr. Scrooge, “the Founder of the Feast.” Even though his family is none too happy to drink to Mr. Scrooge’s health, they dutifully follow their father’s lead. Thus, compacted into a minute’s worth of action, Scrooge feels compassion for Tiny Tim, learns that the boy will die unless something unexpected happens, is confronted by his former hard-heartedness, repents profoundly, and then witnesses the extraordinary grace of his mistreated clerk, Bob Cratchit. Now that’s a formula for personal transformation!

Dickens uses Tiny Tim, perhaps more than any other character, to warm the icy heart of Ebenezer Scrooge. This reflects Dickens’s own experience of being touched by children, especially their suffering. I noted earlier in this series that the first sign of tenderness in Scrooge comes as he observes his own childhood loneliness. This prepares him to be compassionate with other children. Dickens once wrote to a friend, “Certainly there is nothing more touching than the suffering of a child, nothing more overwhelming” (Annotated Christmas Carol, p. 97).

The Strange Ending of Stave III

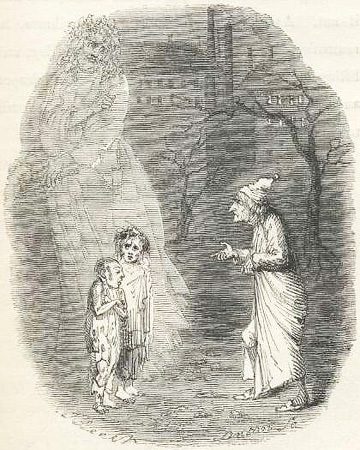

Dickens’ conviction about the suffering of children no doubt explains the bizarre and unexpected conclusion to Stave III. As the Ghost of Christmas Present nears the end of his mission to save Scrooge, he reveals two children hiding beneath his robe. They are “wretched, abject, frightful, hideous, miserable.” Who are these emaciated beings? “This boy is Ignorance. This girl is Want.” Their presence calls forth compassion from Scrooge, who asks, “Have they no refuge or resource?” Once again the spirit hurls Scrooge’s own words back in his face: “Are there no prisons? Are there no workhouses?” And with this, the Ghost of Christmas Past disappears along with his pitiful children.

So what in Stave III contributes to the transformation of Scrooge’s heart? I’ll answer this question in my next post and add some theological reflections.

Why Did Ebenezer Scrooge Change? Stave III (Part 2)

In my last post in this series, I began considering what in Stave III contributes to the transformation of Ebenezer Scrooge’s heart. I summarized the events of Stave III, focusing especially on Scrooge’s response to children in need: Tiny Tim of the Cratchit family and the two wretched children who hide under the robe of the Ghost of Christmas Present. Today, I want to offer some conclusions and reflections on the events of Stave III.

What in Stave III Contributes to the Transformation of Scrooge?

What in Stave III contributes to the transformation of Scrooge’s heart? Partly, it’s the observation of Christmas celebrations, especially those of common folk, most of all the poor, who, in spite of their material deprivation, enjoy the jovial spirit of Christmas.

Yet even more powerful than this observation is Scrooge’s vision of children who suffer (Tiny Tim and the two children who hide under the robes of the Ghost of Christmas Present, Want and Ignorance). Like Dickens, Scrooge finds himself moved by the plight of a child in need. Yet the Spirit of Christmas Present doesn’t merely allow Scrooge’s heart to be touched by childhood pain. He also confronts Scrooge twice with his own words of scorn for the poor. In response to the first of these, Scrooge repents with much sadness. We don’t know of how he responds to the second confrontation, however, because the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come Makes his appearance before Dickens can relate Scrooge’s feelings.

In Stave III, Scrooge also witnesses people whom he has treated poorly extending grace to him. His nephew, Fred, and his clerk, Bob, both drink to Scrooge on Christmas and wish him well. The scene at Fred’s party ends this way:

“A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to the old man, whatever he is!” said Scrooge’s nephew. “He wouldn’t take it from me, but may he have it, nevertheless. Uncle Scrooge!”

Uncle Scrooge had imperceptibly become so gay and light of heart, that he would have pledged the unconscious company in return, and thanked them in an inaudible speech, if the Ghost had given him time.

Grace is invading Ebenezer Scrooge’s heart.

Theological Reflections

Can joyful celebration actually change people? Sometimes I think Dickens has too much confidence in the power of celebration to thaw Scrooge’s heart. Yet, I have seen this sort of thing happen. For example, during my tenure as Senior Pastor of Irvine Presbyterian Church, perhaps the strangest worship service of the year occurred on the Sunday following our Vacation Bible School week. In our Sunday worship services, worship leaders dressed in costume and led children’s songs with lots of hand motions. The children were exuberant in their worship and predictably wiggly and noisy during times of prayer and Scripture reading. The “sermon” was a dramatic sketch in which I and a couple of my colleagues are dressed up as wacky characters who inevitably discovered the truth of the Gospel in spite of our silliness.

Children loved VBS Sunday. No surprise here. But what about the grown ups? When we first did VBS Sunday this way, I was afraid that some of our more sedate and refined adults would be upset. Was I ever wrong! They loved it just as much as the children, in some ways even more. There was something about the unsophisticated celebrations of children that allowed even very grown up people to rejoice, sometimes even clapping their hands or joining the children in their hand motions during songs. So, given the right circumstances, I do think that celebration, especially that of children, can be contagious.

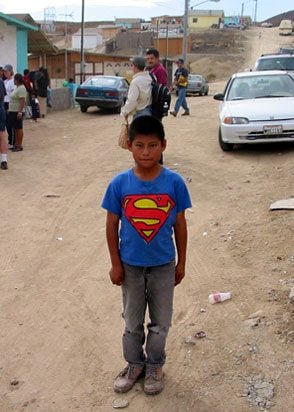

I also agree with Dickens that the suffering of children, perhaps even more than their celebration, can open hearts in a unique way. Consider, for example, the case of African children orphaned because of AIDS. Their tragedy has touched the hearts of millions, even people who might have been reticent to care about the HIV/AIDS crisis because of its association with sexual immorality.

Moreover, World Vision and other charitable organizations have found that people will give generously to help hungry children even when they might be less inclined to help equally hungry adults. If you go to World Vision’s website, you’ll find pictures of struggling children, along with ways to contribute to their well-being. When I visited the website today, a giant headline on the page read: “SPONSOR A CHILD TODAY.” But you won’t find nearly as many pictures of adults in similar distress. This is not an accident. Partly, it reflects World Vision’s laudable focus on children. It also reflects a realistic judgment of what moves people to give. I’m not criticizing World Vision for this, please understand. In fact, my family and I regularly contribute to World Vision and we make a special gift at Christmastime. If you are looking for a place to make a special year-end gift, I can think of no better one. My point is simply that children in need can open the hearts of people like nobody or nothing else.

Dickens is right to realize that compassion alone won’t change people’s hearts, however. The Ghost of Christmas Present rightly confronts Scrooge with his own hard-heartedness, that which Christians call sin. Scrooge needs, not just an infusion of kindness, but a complete change of heart. And this requires repentance and reformation.

Once again, I see Dickens’ understanding of human nature to be much in accord with Christian anthropology. Christians believe that the transformation of human beings requires repentance. In fact, we believe that a Spirit, in this case, the Holy Spirit of God, brings conviction of sin so that we might turn to God (see John 16:7-11).

The complete transformation of Ebenezer Scrooge doesn’t happen at the end of Stave III, however. More is still needed. To this I will turn in my next post in this series.

Why Did Ebenezer Scrooge Change? Stave IV

The final Spirit to visit Ebenezer Scrooge is the “Ghost of Christmas Yet To Come” or simply the “Ghost of the Future.” This silent Spirit, shrouded in black, takes the mythic form of death. Not surprisingly, the visions it reveals to Scrooge also focus upon death and its meaning.

The largest portion of Stave IV, which is shorter than Staves II and III, describes various reactions to the death of some unknown figure. At first, several men of business talk about this man’s death with curious indifference. Then Scrooge observes three people who robbed the dead man and are selling their booty in a creepy part of town. Of course, the reader guesses that the deceased victim is none other than Scrooge himself, but this doesn’t occur to Scrooge at this stage in the story, or, at any rate, he is unwilling to acknowledge what he senses. In fact, when he stands next to the covered body of the dead man, Scrooge is unable to lift the covering and discover whose body lies beneath it. He just can’t bring himself to face his own mortality.

The most touching scene in Stave 4 involves the Cratchit family, minus Tiny Tim, who has just died. Their shared grief is almost tangible as they try nevertheless to enjoy a bit of Christmas cheer. Even so, Bob Cratchit breaks down with sadness, crying out “My little child!” Before Scrooge leaves the Cratchits, the family members resolve never to forget Tiny Tim, whom the narrator addresses: “Spirit of Tiny Tim, thy childish essence was from God.”

In the final scene of this stave, Scrooge demands that the Spirit reveal the identity of the mysterious dead man. Soon Scrooge stands in a deserted graveyard, directed by the Spirit’s pointing finger to a neglected grave, the stone of which reads “Ebenezer Scrooge.” The horrified Scrooge realizes the sum total of his life, which amounts to zero (or less). He will die unloved and unnoticed, unless he chooses a different course of living from that moment on.

This is exactly what Scrooge resolves to do, even though the Spirit refuses to assure him that his life is redeemable: “Spirit!” he cried, tight clutching at its robe, “hear me! I am not the man I was. I will not be the man I must have been but for this intercourse. Why show me this, if I am past all hope? . . . I will honor Christmas in my heart, and try to keep it all the year. I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future. The Spirits of all Three shall strive within me. I will not shut out the lessons that they teach. Oh, tell me I may sponge away the writing on this stone!”

Yet the Spirit doesn’t speak, and, as Scrooge attempts to hold him, the Spirit turns into a bedpost, Scrooge’s own bedpost. His interaction with the spirits is over, and his new life is about to begin.

One might wonder why Dickens associates the Ghost of Christmas Yet To Come with death. Michael Hearn, in The Annotated Christmas Carol, cites something Dickens wrote eight years after A Christmas Carol was first published:

“Of all days in the year, we will turn our faces towards that City upon Christmas Day, and from its silent hosts bring those we loved, among us. City of the Dead, in the blessed name wherein we are gathered together at this time, and in the Presence that is here among us according to the promise, we will receive, and not dismiss, thy people who are dear to us!” (Hearn, p. 126)

Dickens seems to have experienced Christmas in the way many others do, as a time for remembering loved ones who have died. Therefore, Christmas itself can lead to the remembrance of death. What appears to have altered Scrooge’s character, however, is not merely the fact of his mortality, but also the fact that his sad death accentuates the worthlessness of his life. The revelations of the Spirit make clear to Scrooge the emptiness of his life as seen from a post mortem perspective.

Theological Reflections

Death, it seems to me, does have a way of refocusing our vision, helping us see what matters most in life. I’ve frequently had this experience as I participate in memorial services, something I have done quite often as a pastor. Considering the death of someone else and the things said about that person after death causes me to examine the value of my own life. When my days on this earth have passed, will I have lived my life to the fullest? What will people say about me when my life has passed?

Moreover, confronting one’s own mortality can, indeed, lead to personal transformation. I think of people I’ve known who have had serious cancer, and who, in the aftermath, have decided to live with new priorities. Yet Christians believe that moving from death to life isn’t something we can will into existence, but requires the regenerating work of God. Indeed, we all need a Spirit, not a Christmas Spirit, but the Holy Spirit of God, to give us new life.

Finally, the theme of “death within Christmas” is also central to Christian theology. Though we celebrate the birth of Jesus at Christmas, we remember that his birth was a precursor to his death on the cross. It’s common to interpret the gift of myrrh as a symbolic foretaste of Christ’s death, since myrrh was used for embalming (see John 19:39). So, from a Christian point of view, the presence of death in A Christmas Carol makes sense.

Evidence of Scrooge’s Changed Life: Stave V

When we left Ebenezer Scrooge in my last post of this series, he had come to the end of the visits by the Spirits of Christmas past, present, and future. In response to these visits, he promised to be a changed man:

“I will honor Christmas in my heart, and try to keep it all the year. I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future. The Spirits of all Three shall strive within me. I will not shut out the lessons that they teach.”

Stave V, the final section of A Christmas Carol, reveals that Scrooge wasn’t lying or exaggerating. He was indeed a new man.

The first evidence of his transformation is his giddy enjoyment of life. He’s almost crazy with joy, especially when he finds out that it’s Christmas day. This stands in stark contrast to the gruff negativity of the former Scrooge.

Apart from silly excitement, what is the first evidence Dickens supplies of Scrooge’s renewal? Generosity, of course. Charity! Given what we’ve seen earlier in this series, namely Dickens’s association of Christmas with helping the poor, we are not surprised that the new Scrooge jumps at the chance to help the family of his clerk, Bob Cratchit, by sending them a giant turkey for their Christmas dinner. Calling this “charity” doesn’t quite get the feel of Scrooge’s action, however. “Playful charity” might be a better description, since he intends to surprise the Cratchits and not even reveal his identity as their patron.

Soon, however, Scrooge’s benevolence takes a more serious and costly turn. As he’s walking the streets, wishing everyone he sees a “Merry Christmas,” Scrooge spies the two “portly gentlemen” who had visited him the previous day, seeking his help for the poor. That was not a pleasant encounter, of course, since Scrooge dismissed the men without the tiniest gift. But the new Scrooge not only greets the two gentlemen warmly, but also offers a surprisingly large financial gift.

The next evidence of Scrooge’s transformation is easily lost if one reads too quickly. It’s not often picked up in dramatic presentations of A Christmas Carol, though it figures prominently in the 1999 film starring Patrick Stewart as Scrooge. Dickens writes simply, “He went to church.” Since we don’t have more to go on than this, we shouldn’t imagine that Scrooge has experienced some sort of religious conversion. Yet Dickens hints that, in some way or another, Scrooge has a new interest in God, or at least in religious observance at Christmas time.

Following church, Scrooge visits his nephew Fred, asking to join him and his wife for Christmas dinner. Together they experience, in Dickens’s inimitable description: “Wonderful party, wonderful games, wonderful unanimity, won-der-ful happiness!”

The last scene in A Christmas Carol mirrors the opening scene, with Scrooge in his office. He hopes to catch Bob Cratchit coming in late, and his wish is fulfilled. Scrooge uses this opportunity to scare poor Bob half to death with his newfound generosity and Christmas joy. He promises to raise Bob’s salary and help his family.

The closing paragraphs of A Christmas Carol explain that “Scrooge was better than his word.” He became like a second father to Tiny Tim. Moreover, he “became as good a friend, as good a master, and as good a man, as the good old city knew, or any other good old city, town, or borough, in the good old world.” Yes, from then on Scrooge “knew how to keep Christmas well,” but his transformation wasn’t limited to one day or one season. Rather, he fulfilled his promise “keep Christmas all year,” both in his joviality and in his generosity.

So, what evidence do we have of Scrooge’s transformation? Most simply, we see joy, generosity, and childlike playfulness. Earlier in this series I explained how central children were to Dickens’ heart, especially his heart for the poor. The suffering of children touched him more than any other suffering. At the end of A Christmas Carol, Dickens shows that if people allow their hearts to be transformed by children, not only will they care for needy children, but also they will become childlike. Even Scrooge’s generosity has an innocent, playful dimension as he surprises both Bob Cratchit and the portly gentlemen.

Theological Reflections

Once more, I’m impressed with the extent to which Dickens’ understanding of human life is similar to my own Christian point of view. Transformation, for Dickens and for the Christian, has both internal and external aspects. It’s a matter both of feeling and of action. The new Scrooge feels new. But he also takes tangible steps to act in new ways in the world, principally through financial generosity and general kindness. This is the sort of thing that happens when a person is transformed, not by Christmas Spirits, but by the Spirit of God.