Does The Gospel of Jesus’ Wife Show That Jesus Was Married?

© Dr. Mark D. Roberts and Patheos, May 2014

You may also be interested in reading:

Was Jesus Married?

A Careful Look at the Real Evidence

____________

Introduction

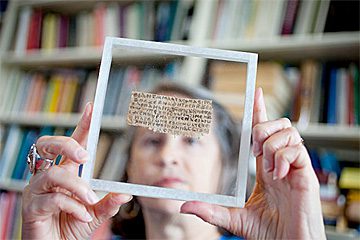

In September 2012, major news outlets reported an astonishing new discovery. A professor at Harvard, Dr. Karen L. King, announced that she was in possession of a fragment of an ancient document. In this fragment, which King named The Gospel of Jesus’ Wife, Jesus appears to refer to Mary Magdalene as “my wife.”

As we might expect, King’s announcement set off a firestorm in the secular media, with hundreds of news outlets running stories, the headlines of trumpeted the discovery that Jesus had, indeed, been married. Professor King, it should be noted, did not claim that The Gospel of Jesus’ Wife tells us anything about Jesus himself. But her scholarly reticence didn’t quell the speculations, not to mention the hysterical headlines.

Shortly after the release of The Gospel of Jesus’ Wife, I wrote a series of blog posts in which I tried to sort out fact from fiction (collected below). This was made difficult by the fact that King had not released all of the data at her disposal. Nevertheless, I examined the fragment and considered its implications for the historical question: Was Jesus married? I concluded, along with Professor King and virtually every other serious scholar, that no matter whether The Gospel of Jesus’ Wife was authentic or not, it shed no light on the marital status of Jesus of Nazareth. Everything I had once written in my series, Was Jesus Married?, was still true.

At that time, I blogged about the fact that a number of serious scholars questioned the authenticity of The Gospel of Jesus’ Wife, believing it to be a modern forgery. But, without additional evidence, the authenticity of the fragment could not be demonstrated or disproved. That judgment would have to wait.

Now, it seems likely that The Gospel of Jesus’ Wife is, indeed, a forgery. There are two main reasons for this.

1. The papyrus of the fragment has been dated by scholars to be no older than the seventh century A.D. But the Coptic dialect of the fragment died out in the sixth century. Thus, it appears that a modern forger had access to an old scrap of papyrus and copied onto it something that would not have been written down centuries ago. The forger didn’t realize the historical mistake being made.

2. Second, and more significantly, the fragment of The Gospel of Jesus’ Wife appears to have been written by someone who clearly forged a fragment of the Gospel of John that exists in the same collection as The Gospel of Jesus’ Wife. If that other fragment is a forgery, and this seems certain to experts in the field, then it is beyond doubt that The Gospel of Jesus’ Wife is also inauthentic. It appears the Professor King and her Harvard colleagues have been fooled by a clever forger.

If you’re looking for the evidence for the points I have just made, let me send you to the excellent blog of Dr. Mark Goodacre, a professor New Testament at Duke. He has many blog posts, some quite technical, that explain in depth the case against the authenticity of The Gospel of Jesus’ Wife (look in April-May 2014).

A Moral of the Story

I expect one could come up with many morals for this story. I will suggest one.

Dr. Karen King is a serious scholar. In fact, she now holds the oldest and arguably most prestigious chair at Harvard University, the Hollis Chair of Divinity. Professor King has contributed substantially to the study of early church history, and, though she has not shied away from hot issues, she is not prone to silliness and sideshows.

When Dan Brown’s novel, The Da Vinci Code, got everybody excited about the non-canonical gospels and their portrayal of women, King jumped into the fray with her book, The Gospel of Mary of Magdala: Jesus and the First Woman Apostle. Yet, her treatment of this gospel was more scholarly than sensational. King took central place among scholars of this gospel and the role of women in gnostic versions of early Christianity.

As I understand it, when King first heard about the manuscript in question in 2010, she considered it to be a forgery. Later, though, she became convinced of its authenticity. She was not aware of the newly discovered reasons to believe that the fragment is a forgery, so she went ahead and treated the fragment as if it were authentic. This now seems to have been a mistake, though, in academia, you can never be quite sure that new evidence or arguments will not muddy the water.

But, for the sake of the moral of this story, let’s assume that the inauthenticity of The Gospel of Jesus’ Wife becomes widely accepted among scholars. King and her Harvard colleagues were bamboozled by a clever forger. What can we learn from this?

I would suggest that King should have been much more skeptical about the peculiar coincidences surrounding the “discovery” of disputed fragment. It does seems strange, doesn’t it, that this fragment was “discovered” in a time when the question of Jesus’ marriage was hot. What are the odds that a genuine piece of ancient writing testifying to the “wife” of Jesus had “come to the kingdom for such a time as this”? That seems pretty fishy to me.

Further, consider the “coincidence” of what we actually have in the fragment. According to Karen King’s translation of the Coptic, here’s what the fragment says;

1 ] “not [to] me. My mother gave to me li[fe…”

2 ] The disciples said to Jesus, “.[

3 ] deny. Mary is worthy of it [

4 ]……” Jesus said to them, “My wife . .[

5 ]… she will be able to be my disciple . . [

6 ] Let wicked people swell up … [

7 ] As for me, I dwell with her in order to . [

8 ] an image [

Now, doesn’t it seem amazing that the only part of this gospel that remains includes specific mention of “Mary” and a statement of Jesus calling her “My wife”? What are the odds of such a thing happening, and happening right at a time when the issue of Jesus’ marriage is a lively one.

Of course coincidences do happen. But as I look at this particular set of coincidences, it seems to me that we either have an outright miracle or a forgery. Either God dropped this fragment into our hands at just this time, or someone else created the fragment for certain reasons (money? influence the debate? or?). Now, as one who believes that God does miracles, I am not closed to the possibility of supernatural interventions. But, it does seem unlikely to me that the Almighty is the one who preserved and delivered the disputed fragment.

So, what’s the moral of the story, for Karen King and for the rest of us? If something is too good to be true, it’s almost certainly too good to be true . . . unless it’s a miracle.

Introduction to The Gospel of Jesus’ Wife

(What follows is what I wrote in September 2012, just after the Karen King’s announcement of her discovery.)

Did Jesus have a wife, after all?

Major news outlets, such as the New York Times, are reporting on the discovery of a new document that refers to Jesus’ wife. More precisely, a small fragment from a previously unknown document contains a statement by a character named “Jesus” referring to “my wife.”

Does this give us new historical evidence for the literal marriage of Jesus of Nazareth to some woman, perhaps Mary Magdalene?

No, says Karen L. King, the scholar who recently revealed the existence of the manuscript fragment in which “Jesus” speaks of “my wife.” In an article to be published in the Harvard Theological Review, King writes:

This is the only extant ancient text which explicitly portrays Jesus as referring to a wife. It does not, however, provide evidence that the historical Jesus was married, given the late date of the fragment and the probable date of original composition only in the second half of the second century.

Near the end of her article, King, with contributions by AnneMarie Luijendijk, reiterates:

Does this fragment constitute evidence that Jesus was married? In our opinion, the late date of the Coptic papyrus (c. fourth century), and even of the possible date of composition in the second half of the second century, argues against its value as evidence for the life of the historical Jesus.

Of course, King’s measured judgment here will do little to stop the coming tidal wave of claims that we now have definitive evidence if not proof that Jesus was actually married. Dan Brown and his spokesman, Sir Leigh Teabing, appear to have been right all along! At least this is what we’ll hear in the days to come.

In fact, as Karen King rightly observes, the discovery and publication of the fragment known as the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife in fact tells us nothing about the first-century man we know as Jesus of Nazareth. If it is genuine, the fragment of the otherwise unknown document will tell us something about the beliefs of people who lived a century or two after Jesus, though what exactly we should conclude on the basis of this small piece of an ancient manuscript is yet to be determined.

Several years ago, I wrote an article called Was Jesus Married? A Careful Look at the Real Evidence. I wrote this in response to the fictional “scholarship” found in Dan Brown’s bestseller, The Da Vinci Code. In this article, I sifted through the historical evidence for and against the marriage of Jesus, focusing on the New Testament as well as writings from early Christianity. I showed that there was no evidence whatsoever in the ancient texts for the marriage of Jesus. Today, I need to qualify what I wrote in light of the new evidence from the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife. I would say something like this:

In light of the recent publication of a fragment from the so-called Gospel of Jesus’s Wife, it seems possible that in the fourth century A.D., somebody wrote or copied a document in the Coptic language in which a character named “Jesus” uses the phrase “my wife.” If we understand this language in a literal sense, which may or may not be the right interpretation, then this fragment provides evidence that somebody (or a group of people) in the second or third century believed that Jesus was actually married.

Of course, it could turn out that the fragment of the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife is a forgery (though given what Karen King has described, I am not expecting this outcome). It could also turn out that the use of “wife” in this document is best understood in a non-literal sense. Part of what makes this case so tricky is the fact that we have very little of the original document (if there was an original document). But, even if, in the end, scholarly consensus supports the genuineness of the fragment and the literal interpretation of “wife,” we would do well to remember Karen King’s conclusion that the fragment “does not . . . provide evidence that the historical Jesus was married.”

If you’re not familiar with Karen King, let me say that she is a serious and highly-accomplished scholar whose particular expertise includes early Christian history and the Coptic language. In other words, she is someone who deserves to be taken seriously in the matter of this manuscript fragment. (Note: I did not know King when I was at Harvard. She came six years after I finished my Ph.D. there.) King is not some huckster who is seeking to make a name for herself from some academically-suspect charade. Moreover, King has served us well by making available a pre-release of her official article (www.hds.harvard.edu/sites/hds.harvard.edu/files/attachments/faculty-research/research-projects/the-gospel-of-jesuss-wife/29813/King_JesusSaidToThem_draft_0917.pdf) that will appear in the Harvard Theological Review (January 2013). Clearly, King is encouraging a serious, responsible debate about the fragment that was made available to her last December (2011). I must give her credit, however, for knowing how to stir up popular interest in this fragment by naming it the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife. (It appears that she named the fragment, though I’m not positive about this.)

Tomorrow, I’ll have more to say about the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife and its implications for our understanding of Jesus. In the meanwhile, if you are looking for serious discussion of this fragment, let me point you to King’s article and some basic information from the Harvard Divinity School website. Also, you may be interested in my online article, Was Jesus Married? A Careful Look at the Real Evidence. As I mentioned above, I will need to edit this a bit to reflect the new data from Karen King. But my basic conclusions about the marriage of Jesus (or lack thereof) remain intact.

More on The Gospel of Jesus’ Wife

Yesterday, I began commenting on the new revelation from Karen King: a small fragment that may come from a fourth-century document that includes a character named “Jesus” who says “my wife.” Of course, this revelation has excited the media, which stirs up business with such catchy headlines as “A Faded Piece of Papyrus Refers to Jesus’ Wife.” The way this reads, you might think the fragment refers to the actual wife of the actual Jesus of Nazareth. Now that will sell some papers, but it won’t help anybody understand what’s really going on here.

Unfortunately, this kind of hype contributes little to our understanding of early Christian history or of the person we know as Jesus of Nazareth. The fragment revealed by King may, if it is found to be authentic, tell us something about religious life a century or two after Jesus. But it doesn’t tell us anything about Jesus himself. As King writes in her soon-to-be-released article in the Harvard Theological Review:

This is the only extant ancient text which explicitly portrays Jesus as referring to a wife. It does not, however, provide evidence that the historical Jesus was married, given the late date of the fragment and the probable date of original composition only in the second half of the second century.

See www.hds.harvard.edu/sites/hds.harvard.edu/files/attachments/faculty-research/research-projects/the-gospel-of-jesuss-wife/29813/King_JesusSaidToThem_draft_0917.pdf

But, in spite of King’s caution, I’m sure the media will soon be saturated all sorts of prophets, professors, and pretenders weighing in on the marriage of Jesus. No doubt many will claim to have found the smoking gun, the telltale evidence for the marriage of Jesus. These folks ought to calm down and read King’s article more carefully. They might also be well-served to read an article I wrote called: Was Jesus Married? A Careful Look at the Real Evidence.

In this blog post, I want to highlight a few salient facts concerning the fragment now known as the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife. In my comments here, I am relying heavily on Karen King’s work and am grateful to her for quickly publishing the evidence so others scholars can weigh in.

What is the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife?

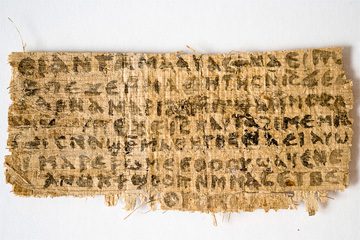

It is not a gospel in the sense that most people might imagine. We do not have anything like the longer gospels in the New Testament or the non-canonical gospels that show up in the Nag Hammadi Library, for example. What we have is a very small papyrus fragment (about 1.5 inches by 3 inches) on which there is written in Coptic, an Egyptian language used in the centuries after Christ. According to Karen King’s translation, here’s how the front of the papyrus reads:

1 ] “not [to] me. My mother gave to me li[fe…”

2 ] The disciples said to Jesus, “.[

3 ] deny. Mary is worthy of it [

4 ]……” Jesus said to them, “My wife . .[

5 ]… she will be able to be my disciple . . [

6 ] Let wicked people swell up … [

7 ] As for me, I dwell with her in order to . [

8 ] an image [

The fact that some character named “Jesus” says “my wife” is clear. Given the mention of disciples and Mary, it seems likely that this fragment, if it is authentic, comes from a longer document that is connected to early Christianity.

Where Did The Fragment of the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife Come From?

This mysterious and undocumented origins of this fragment add to its intrigue. According to Karen King, the fragment belongs to a private collector who wishes to remain anonymous. The owner gave the fragment to Karen King in December, 2011 so that she might examine it and, apparently, make its contents known. The fragment appears to have been part of a private collection in the 1980s. Nothing is known of the earlier history of the fragment at this time.

Could the Fragment Be a Forgery?

Given the peculiar history of the fragment and its seemingly incendiary content, it could be a forgery. It seems curious to me that the fragment is so neatly rectangular, unlike many ancient manuscript fragments. But, according to King, who is herself an expert in the field of early Christian history and the Coptic language, she has allowed other experts to examine the document and verify its authenticity. You can find the details in her article. If it’s a forgery, it is very well done. At the moment, I would assume for the sake of discussion that the fragment is authentic. But I could certainly be wrong about this. Several international experts have expressed grave doubts about the authenticity of the fragment.

When Was the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife Written and by Whom?

Of course, if the fragment is a forgery, then this question has an especially juicy answer. But, if it is authentic, then there are actually two questions that need to be answered:

1. When was this particular fragment copied?

2. When was the original “gospel” authored?

Scholars answer the first question by careful study of the details of the fragment: handwriting, ink, papyrus, language, etc. King believes that the fragment itself was penned in the fourth century A.D. (in the 300s).

The second question requires even more guess work, especially given the tiny amount of information contained on the actual fragment. King argues that the original document was written in the second half of the second century A.D. Moreover, she concludes: “There is insufficient evidence to speculate with any confidence about who may have composed, read, or circulated GosJesWife except to conclude they were Christians.” Of course, she is using “Christians” here in a historical sense. She is not claiming that those who wrote or used this document were orthodox believers. In fact, King sees this document as at home among Gnostic writings that were clearly not in the orthodox Christian stream.

Though it’s possible that GosJesWife was written during the latter half of the second century, we should remember that this is speculative, given how little we know about the larger document from which the fragment comes. Some scholars of early Christianity, and especially agenda-driven pseudo-scholars, try to push the dating of the Gnostic gospels earlier and earlier. Watch and you’ll see what I mean. Karen King has a scrap of a fourth-century document. She argues, plausibly, but without making any claim to certainty, that the original document was written over a hundred years earlier, in the late second century. Yet, before long, you’ll find people who will assert that GosJesWife comes from early in the second century. Then, some will claim that the content of GosJesWife represents first-century traditions. This is how the game works. (I’ll have more to say later about why people in today’s world might want to think of Jesus as married.)

What Does the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife Tell Us About “Jesus’s” Wife?

Not much, actually. This fragment tells us very, very little even about the character named “Jesus” who appears in the second and fourth lines of the fragment. In the first line, he says “My mother gave to me li[fe. . . .” In the second line, his disciples speak to Jesus. In the third line, it seems that Jesus mentions someone named “Mary” who is “worthy” of something. In the fourth line, Jesus identifies someone (presumably but not necessarily Mary) as “my wife.” In the fifth line, he adds that she “is able to be my disciple.” In the seventh line, he says “I dwell with her.”

Given how little we have here, there is much we do not know. We do not know, for example, whether the name “Mary” (l. 3) refers to the mother of Jesus (l. 4), the wife of Jesus (l. 4), or some other person. It seems to me likely that “Mary” is the name of Jesus’s wife, but this cannot be known for sure.

We also do not know the sense of “wife.” We might be inclined to take “wife” literally, as the person who was married to Jesus and lived with him in consummated intimacy. But, given the Gnostic tendency to denigrate fleshly existence, it’s possible that “wife” was not meant in this literal way, but rather in some figurative sense, perhaps as one with whom Jesus shared his most intimate revelations.

It does seem clear in GosJesWife that the wife of Jesus was his disciple, at least as far as he was concerned. As Karen King argues, the dialogue bears resemblance to what we find in other Gnostic “gospels” from the late second and early third centuries, such as The Gospel of Mary and The Gospel of Philip. (I have examined these documents in my article, Was Jesus Married?) There does appear to have been a debate among some Gnostic Christians as to the role of Mary in relationship to Jesus. Perhaps certain of these Gnostics believed that Mary’s role as Jesus’s wife somehow underscored her worthiness to be his disciple. (Of course, in the biblical gospels, Mary Magdalene is a close follower of Jesus who does not need to be married in order to be accepted by him. Women and men were free to follow Jesus without being members of his literal family. His acceptance of women followers was part of what made Jesus so scandalous in his own time and culture.)

Does the Gospel of Jesus’ Wife Provide Evidence for the Actual Marriage of the Actual Jesus?

No, it doesn’t. If the fragment is authentic, and if the use of “wife” in this fragment was meant to be understood literally, if the original document was penned late in the second century, then, at most, we have evidence that some (Gnostic) Christians who lived a century and a half after Jesus believed that he was married. Such things can fascinate those of us who enjoy studying early Christian history. But they don’t tell us anything about Jesus himself. As Karen King concludes in her article:

Does this fragment constitute evidence that Jesus was married? In our opinion, the late date of the Coptic papyrus (c. fourth century), and even of the possible date of composition in the second half of the second century, argues against its value as evidence for the life of the historical Jesus.

Why Is There So Much Interest in the Marriage of Jesus?

A few days ago, a scholar at the Tenth International Congress of Coptic Studies in Rome announced the discovery of a tiny fragment of a manuscript, which, if authentic, comes from the fourth century A.D. This kind of academic presentation wouldn’t even make the back page of American newspapers, let alone the headlines, except for one small detail: the fragment involves a speaker named “Jesus” who mentions “my wife.” All of a sudden, an extraordinarily obscure academic presentation makes headlines throughout the world.

Why? Why is the supposed marriage of Jesus such a big deal these days?

There are many different ways to answer this question. I will suggest a six perspectives here, three in today’s post and three in my next post in this series on the marriage of Jesus. As always, I welcome your input, either in comments or by email.

1. The Marriage of Jesus is a Big Deal Because of The Da Vinci Code

Dan Brown’s novel The Da Vinci Code put the question of Jesus’ marriage on the cultural map. Prior to the publication of the novel in 2003, the question of Jesus’ marriage was something that entertained a few scholars of antiquity, most of all one Presbyterian pastor and professor who, in 1970, wrote a book entitled Was Jesus Married? The Distortion of Sexuality in the Christian Tradition. Yet, for the most part, nobody cared about his book or the question of Jesus’ marriage.

Dan Brown’s novel The Da Vinci Code put the question of Jesus’ marriage on the cultural map. Prior to the publication of the novel in 2003, the question of Jesus’ marriage was something that entertained a few scholars of antiquity, most of all one Presbyterian pastor and professor who, in 1970, wrote a book entitled Was Jesus Married? The Distortion of Sexuality in the Christian Tradition. Yet, for the most part, nobody cared about his book or the question of Jesus’ marriage.

But, then came The Da Vinci Code and all of a sudden the question of Jesus’ marriage was a big deal in popular culture (which stirred up scholarly interest as well). In Dan Brown’s engaging fiction, the marriage of Jesus involves one of the greatest cover-ups in human history. It is the central solution of a perplexing mystery. And the denial of Jesus’ historical marriage to Mary Magdalene explains the success of the oppressive Roman Catholic Church and its failure to be faithful to Jesus’ vision for his church.

Although Dan Brown wrote a novel and his “scholarship” was fiction based on a few tidbits of truth, his influence was wide and deep. Many readers accepted the “historical” claims of Brown’s character Sir Leigh Teabing about the marriage of Jesus as if they were true. My son’s eighth grade history teacher, for example, told my son’s class that sexism really didn’t exist before Christianity and that Jesus meant for Mary Magdalene to lead his church, but the Roman Catholic hierarchy squelched Mary because she was a woman. Yes, this was a history class, not a fiction class. This episode points to a second reason why the marriage of Jesus is such a big deal today.

2. The Marriage of Jesus is a Big Deal Because It Appears to Undermine Orthodox Christianity

According to historic Christian tradition, Jesus was not married. So, if it turns out that Jesus was in fact married, this appears to undermine orthodox Christianity. And there are quite a few people these days who would like to do some undermining.

Now, I’m not claiming that everyone who believes Jesus was married is anti-Christian. But, I am noting that anti-Christian folk are attracted to the idea of a married Jesus. To be sure, this notion contradicts classic Christian belief about the single, celibate Jesus. Yet, it can be argued that a married Jesus could still be the divine Son of God and Savior of the world. So, the purported marriage of Jesus does not necessarily undermine the core of Christian faith, even though it troubles the theological water. Nevertheless, those who dislike Christian orthodoxy are often drawn to the idea of a married Jesus.

3. The Marriage of Jesus is a Big Deal Because It Appears to Raise the Status of Women

You can find a connection between the married Jesus idea and feminism in a variety of sources, including but not limited to The Da Vinci Code. Some scholars and others have put forward the case that Jesus’ having Mary Magdalene as his wife gives women a higher ranking in the church and the world, if not in God’s pecking order.

This is an odd argument, in my view. For one thing, the fact that Jesus was born of a woman already suggests that women are rather special in God’s dispensation. But, it is oddly patriarchal to suggest that Mary Magdalene draws her authority and significance from the fact that she is a wife. In the New Testament gospels, Mary is a close follower of Jesus and the first human being to announce the good news of his resurrection. She plays a unique and privileged role among his followers, not because she is Jesus’ wife, but because Jesus calls women and men to be his disciples. One could very well argue that the notion that Mary’s significance depends on her being married to Jesus does the opposite of raising the status of women.

4. The Marriage of Jesus is a Big Deal Because It Seems to Affirm Human Sexuality

If Jesus was literally married to some woman, whether Mary Magdalene or some other person, then we would assume he was sexually intimate with this person. For many people today, this is part of the excitement (and scandal) of the married Jesus. If Jesus had a wife, then sexuality gets an ethical and theological promotion.

To be sure, some Christians associate all sexuality with sin. This is one main reason they cannot tolerate the idea of a married Jesus. The fact that God created sex as something good, something to be shared between a man and woman as they become “one flesh,” something that enables humankind to be literally fruitful and multiplying, is forgotten. But, we are told, the marriage of Jesus endorses sexual intimacy. It seems to correct an error in the thinking of many Christians.

I can understand this perspective. What I find odd, however, is that the “married Jesus” perspective seems to have thrived, if it thrived at all, among Gnostic Christians who actually minimized the value of fleshly existence. They prized the spirit and ignored or denigrated the flesh. Thus, those who might have believed that Jesus was actually married and sexually active held a view of human life that undermines a healthy, holy sexuality. If you’re looking for positive affirmations of human sexuality, you’d be much better off with the Bible than with Gnostic speculations.

5. The Marriage of Jesus is a Big Deal Because It Appears to Make Jesus More Human

Eight years ago, in response to the popularity of Dan Brown’s novel The Da Vinci Code, I wrote an online article called Was Jesus Married? A Careful Look at the Real Evidence. I concluded that the historical evidence for the marriage of Jesus was virtually non-existent. (In fact, if the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife is authentic, it supplies the only piece of clear ancient historical evidence for a wife of Jesus other than a circumstantial argument based on the incorrect assertion that all Jewish men in Jesus’ day were married. Of course, the actual evidence from the fragment of this “gospel” amounts to just a tiny bit more than zero, so I would still say the evidence for the marriage of Jesus is virtually non-existent.)

When I wrote my article on the marriage of Jesus, I never anticipated the responses I would get from dozens of people. Through comments left on my blog or through emails, readers let me know how much it meant to them to think of Jesus as married. Almost always, their main point was that a married Jesus seemed to be a much more human Jesus, a Jesus they could relate to, a Jesus they wanted to know and follow. Many of those who wrote to me were Christians who had envisioned a distant, judgmental, inhuman Jesus before they began to picture him as married. For them, Jesus had been 90% divine and 10% human (at most). A married Jesus balanced the scales, or tilted them in favor of Jesus’ humanity.

I do understand that certain streams of Christian tradition have so emphasized the deity of Christ that his humanity has been lost. The classic formula of “fully God and fully human” may have been affirmed in principle. But, in the faith and piety of some Christians, Jesus is “mostly God and barely human.” This kind of Jesus feels distant, judgmental, and uncaring. Yet, for many whose sense of Jesus obliterates his full humanity, a married Jesus brought him back to earth.

If you know anything about early Christianity, you can identify a giant irony here. The Jesus-with-a-wife tradition seems to have existed among those whose Christianity was Gnostic. The essence of Gnosticism involved a denial of the value of fleshly existence. Salvation was the deliverance of spirit from the prison of flesh. The “Savior” in Gnostic speculation is not fully human at all. In fact, many of the Gnostics claimed that the real Christ was not the Word of God Incarnate, was not truly human, and did not actually die on the cross. These things were just illusions or the actions of an imposter. So, historically speaking, belief in a married Jesus seems to be associated with an understanding of the Savior as not truly and fully human. Those who are drawn to a married Jesus because it makes him seem more human are at odds with those who originally cooked up the story of a married Jesus.

6. The Marriage of Jesus is a Big Deal Because Jesus is a Big Deal

Even in our increasingly secular Western culture, and even in a world of wide religious and philosophical diversity, Jesus is still a big deal. Democrats and Republicans want Jesus on their side. So do Methodists, Mennonites, Mormons, and Muslims. Oh, there may be a few enthusiastic atheists who are done with Jesus, but they are plainly in the minority. Most people still care a whole lot about Jesus, or at least the Jesus of their own imaginations. Thus, if someone comes up with a novel claim about Jesus, especially if that claim seems to contradict classic Christian teaching, then folks get excited. Jesus still has the power to upset the apple cart as well as to sell newspapers and drive up the traffic to your web site.

I expect that, before too long, the tempest associated with the Gospel of Jesus’ Wife will die down. The fragment of this “gospel” may end up being judged by most scholars to be a forgery. But, even if it is seen as authentic, the fragment’s irrelevance will soon overwhelm the hype.