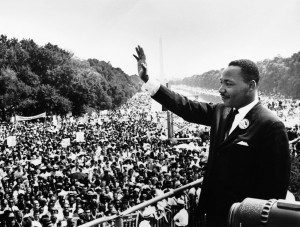

As I read through the articles on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech from 50 years ago today, I was fascinated by the account in The New York Times. It told a story from the platform that I had never heard before.

As I read through the articles on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech from 50 years ago today, I was fascinated by the account in The New York Times. It told a story from the platform that I had never heard before.

Dr. King was about halfway through his prepared speech when Mahalia Jackson — who earlier that day had delivered a stirring rendition of the spiritual “I Been ’Buked and I Been Scorned” — shouted out to him from the speakers’ stand: “Tell ’em about the ‘Dream,’ Martin, tell ’em about the ‘Dream’!” She was referring to a riff he had delivered on earlier occasions, and Dr. King pushed the text of his remarks to the side and began an extraordinary improvisation on the dream theme that would become one of the most recognizable refrains in the world.

With his improvised riff, Dr. King took a leap into history, jumping from prose to poetry, from the podium to the pulpit. His voice arced into an emotional crescendo as he turned from a sobering assessment of current social injustices to a radiant vision of hope — of what America could be. “I have a dream,” he declared, “my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today!”

Nobody knows if he planned to do the riff anyway, but I had no idea that the most famous portion of his remarks that day were not even in the written text. I don’t know which is my favorite, the “I have a dream” riff or the “I’ve been to the mountain top” riff that he delivered in Memphis the night before he was assassinated. King has to go down as one of the greatest American orators of the 20th Century.

As I reflect on Dr. King’s legacy and the work he did I think what a courageous life he lived. I’m reminded of the power of non-violence, and the incredible patience of civil rights leaders. Courage and patience, two necessary virtues for those who work for justice. Still, racial inequality is alive and well today, and I must confess how little I do to work against it. Injustice is still embedded in the systems of our society, and income inequality is still largely organized by race. We still have a lot of work to do.

I’m thankful that the 50th anniversary of this phenomenal speech is receiving such attention. I hope that it will renew our passion to pursue social justice. Stanley Hauerwas has often remarked that one of the unintended consequences of electing a black president is the tendency to believe that racial inequality has finally been resolved. Of course we know it hasn’t. An interesting article at Bloomberg cites evidence.

Since the June 2009 end of the recession, median income for black households has dropped 10.9 percent, compared with a 3.6 percent fall for white households, Sentier Research, an economic-consulting firm in Annapolis, Maryland, said last week.

Today, while the poverty rate for blacks has improved over the last five decades, it’s still greater than one in four — and almost three times worse than for whites.

In 1966, the closest year from the speech for which census data are available, 42 percent of blacks lived in poverty compared with 11 percent of whites. By 2011, 28 percent of blacks were impoverished compared with less than 10 percent of whites.

While the nation’s 44.5 million blacks made up 14.2 percent of the population in 2012, they were only 8.9 percent of college graduates and held 8.2 percent of management and professional jobs, according to census and Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

Most alarming from the Bloomberg article is the income gap:

Five decades after King spoke of the “great vaults of opportunity of this nation,” median black family income is more than 40 percent below that of whites. As of June, black households were earning an annual median of $33,519 compared with $58,000 for whites, according to Sentier Research.

Another interesting article you might read is by economist Joseph Stiglitz. “Like so many looking back over the past 50 years,” Stiglitz says, “I cannot but be struck by the gap between our aspirations then and what we have accomplished.” He tells the story of his participation in the March on Washington, in which he adds this critique of the current Supreme Court.

The night before the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, I had stayed at the home of a college classmate whose father, Arthur J. Goldberg, was an associate justice of the Supreme Court and was committed to bringing about economic justice. Who would have imagined, 50 years later, that this very body, which had once seemed determined to usher in a more fair and inclusive America, would become the instrument for preserving inequalities: allowing nearly unlimited corporate spending to influence political campaigns, pretending that the legacy of voting discrimination no longer exists, and restricting the rights of workers and other plaintiffs to sue employers and companies for misconduct?