—

“Bad liturgy eventually leads to bad ethics. You begin by singing some sappy, sentimental hymn, then you pray some pointless prayer, and the next thing you know you have murdered your best friend.”

– Stanley Hauerwas & William Willimon, The Truth About God.

—

I was recently offered the opportunity to write on the following assigned topic: “make realistic and judicious suggestions about how individuals, communities, and even larger social units… might contribute to peace within families, between adversaries, in the political arena, and even on a global scale.”

I know of only one suggestion I could make: Worship.

I don’t mean worship as in singing a bunch of Chris Tomlin songs with two thousand of your closest friends. The kind of worship I’m recommending cannot happen in a mega church, or any church that is obsessed with church growth. Theologian Stanley Hauerwas once wrote, “Bad liturgy eventually leads to bad ethics. You begin by singing some sappy, sentimental hymn, then you pray some pointless prayer, and the next thing you know you have murdered your best friend.” If Hauerwas is correct, much of what passes for contemporary worship will lead to violence.

I’m talking about a different kind of worship: participation in the life of a local church that is so rooted in a neighborhood, in the scriptures, and in the traditions of the Christian faith that they become hospitable to those they would otherwise leave out.

I’m talking about worship that includes those living on the margins of society.

The church I pastor in Kansas City is called Redemption Church. It’s a small congregation of maybe two hundred people, fifty or sixty of whom are homeless. Members of Redemption offer rides to and from church, a hot shower, coffee, donuts, and a chance to participate in worship to our members who live off the grid. Most of our homeless members are in the throes of addiction, mental illness, or they are hiding from the law. Many come in various stages of insobriety, hoping to sneak a drink or hit of something while they are with us.

Our homeless brothers and sisters are not a project; they are simply part of our church. Yet, the reality is that their participation in worship causes tension—not unlike the tension created in a family when one member has an active addiction. It has taken many years for our congregation to make space for the “crazy” that comes along with homelessness. Worshipping together requires constant adjustment.

One Sunday a homeless man came to receive communion. As he took a piece of bread and dipped it in the cup I saw that his hands were dirty, his fingernails blackened from whatever he had been smoking. He plunged his grimy fingers a couple of inches below the surface of the liquid and received the bread.

Out of the corner of my eye I noticed that the girl who was next in line saw those blackened fingers dip down into the cup as well. I know this woman to be a kind and loving soul. As our eyes met, a moment of understanding passed between us. She was next. She had to dip her bread in the cup not knowing what was on those fingers. “’Remember the body and blood of Christ,” I said. She grabbed a piece of bread, plunged it into the cup, and put it in her mouth. I could see her having to almost choke down the body of Christ.

The memory of my friend having to choke down the body of Christ in order to share this common meal with someone who is terribly addicted and broken is seared into my consciousness. Worship should be costly in just such a way.

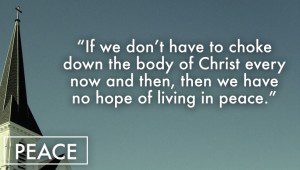

Worshipping with “the other” in all its forms requires us to choke down the hostility we would otherwise feel toward those who are not like us, those with whom we are most likely to end up in some kind of violent confrontation. Worship is meant to train us in this proficiency. If we don’t have to choke down the body of Christ every now and then, then we have no hope of living in peace.

Worshipping with “the other” in all its forms requires us to choke down the hostility we would otherwise feel toward those who are not like us, those with whom we are most likely to end up in some kind of violent confrontation. Worship is meant to train us in this proficiency. If we don’t have to choke down the body of Christ every now and then, then we have no hope of living in peace.

Peace is not an accomplishment or a status. Peace is an orientation of the soul that is formed by a community of peace. In a society such as ours (a community steeped in violence), the soul must undergo serious training in order to cultivate the willingness to suffer violence rather than commit violence. Nowhere else in Western society does that kind of soul-formation have the potential to happen except in the local church.

Not that participation in most American churches would constitute a guarantee against the kind of individualistic, self-referential lifestyle that inevitably leads to violence, (See Hauerwas above). But, if there’s any place left in our culture where a human being can be formed by a different story—one that is defiant in the face of the inhuman, inhumane, and dehumanizing nature of American life—it would have to be the church… and not just any church.

But, in order for a church to train its members for peace it must include in its worship those we are tempted to avoid: the poor, marginalized, and mentally ill, those who are racially different from us, the undocumented alien, our neighbors in the LGBT community, anyone who might often be left out or left behind, and so on. Participation in such a community can train us for peace precisely because it would require us to make space for other people’s “crazy.” We all have some crazy; a freak flag; those quirks, foibles, oddities, deficiencies, prejudices, and eccentricities that make us hard to love.

This kind of worship is nearly always inconvenient and costly, but scripture consistently teaches that if worship costs us nothing, then it has no value to God, or to us. However, worship that requires us to make space for otherness holds great value.

Worship involves the kind of intimacy that mitigates violence. Worship requires an absence of hostility. Jesus was explicit about this command. “If you are angry with a brother or sister, you will be liable to judgment… So when you are offering your gift at the altar, if you remember that your brother or sister has something against you, leave your gift there before the altar and go; first be reconciled to your brother or sister.” (Mt. 5:22-24). Apparently there is no way to draw closer to God without drawing closer to one another.

When we worship we become vulnerable to those who may hurt us. We lay down our weapons, grievances, grudges, anger and hostility in order to approach the communion table, or we do not approach at all. If we want to pursue peace, then we need to worship not only with the poor and the marginalized, but also with our enemies.

When we worship with “the other”—especially those who make us uncomfortable, whose presence feels offensive or distasteful, those toward whom we feel a sense of hostility—we will automatically feel tension. God’s plan seems to be to use this tension to help our soul shift toward peace.

The hostility we feel toward those who are not like us is acceptable in almost every other part of our society, but it is distinctly out of place in Christian worship. Any hostility toward “the other” offends God, and it offends the community. As we worship together, we are forced to give it up. Only then are we free to make any lasting movement toward peace.