Hard-charging Cabinet member served three presidents, but conversion to Christianity mellowed him as he aged.

By Warren Cole Smith

News of the death of James Schlesinger on Mar. 27 at age 85 was a mild shock to my system because of a brief but memorable meeting I had with him 35 years ago.

News of the death of James Schlesinger on Mar. 27 at age 85 was a mild shock to my system because of a brief but memorable meeting I had with him 35 years ago.

In the fall of 1979 I took a break from my college career at the University of Georgia to do an internship with Sen. Sam Nunn, then early in his second term representing Georgia. One of the great things about working for a fairly junior senator is that offices get doled out based on seniority, and Sam Nunn’s staff had small, inadequate offices. That was not good for the Senator and his senior staff, but it was great for me. It meant that I worked at the elbow of Nunn’s senior staffers, and saw Sen. Nunn nearly daily. Watching them, seeing how they conducted themselves, listening to them on the phone – that was more of an education that any of the mostly menial jobs they assigned me during my internship.

Georgia had a tradition of sending men to Washington who advocated a strong national defense. The legendary bachelor senator Richard Russell served 40 years in the Senate, from the 30s through the 70s, shaping America’s military policy as much as any man alive during the 20th century. Another Georgian, Carl Vinson, spent 50 years in the House of Representatives. Vinson, often called “The Father of the Two Ocean Navy,” had an aircraft carrier named after him while he was still alive, an unprecedented honor for a Member of Congress.

Carl Vinson was also Sam Nunn’s great uncle. So when Nunn came to the Senate, he knew he had big shoes to fill. He had managed to wrangle himself a seat on the Senate Armed Services Committee, and was even chairman of the Subcommittee on Manpower, but to be taken seriously he needed to exercise some thought leadership on defense issues.

So he planned to give a major policy speech on the floor of the Senate to air his views on the second Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty, often called SALT II. The United States and the Soviet Union had signed the treaty just months earlier, in June of 1979, but the Senate had not ratified it. Whether the Senate would ratify it or not depended much upon Sen. Nunn’s position, and Nunn was a skeptic. He was in favor of nuclear arms reduction. Indeed, in later years Nunn founded the Nuclear Threat Initiative, which seeks to reduce the threat of nuclear weapons. But he did not want to disarm America’s nuclear arsenal without a buildup in America’s conventional defense capabilities. Because of his position on the Armed Services Committee and because the president who signed that treaty, Jimmy Carter, was a fellow Georgian and a fellow Democrat, much depended on Sen. Nunn’s SALT II speech.

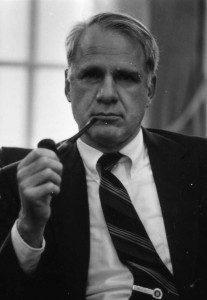

For these reasons Nunn sought the input of James Schlesinger. Schlesinger, then 50, was in the midst of a remarkable career of public service, but he was near the end of a controversial career in “official Washington.” He had been the Director of Central Intelligence under Richard Nixon, Secretary of Defense under Nixon and Gerald Ford, and Secretary of Energy – the nation’s first – under Carter. He was a brilliant strategist, but he had a reputation for not suffering fools gladly. Everywhere he went he cut budgets, slashed staff, and reorganized workflow. That meant that he left every organization he led more efficient, more mission-focused – and with a lot of enemies in his wake.

One notable example: His tenure as director of the CIA during the Nixon Administration was less than six months long, but during that time he fired more than 1000 of the agency’s 17,000 employees. CIA insiders said only half-jokingly that the security camera in the lobby of the agency’s Langley, Va., headquarters was there to keep people from defacing Schlesinger’s official portrait.

In July of 1979, Schlesinger left the last full-time government job he would ever have, fired by Jimmy Carter as Energy Secretary. Journalist (and former Bill Clinton speechwriter) Paul Glastris wrote, “Carter fired Schlesinger in 1979 in part for the same reason Gerald Ford had—he was unbearably arrogant and impatient with lesser minds who disagreed with him.”

But according to Arnold Punaro, Nunn’s military advisor at the time, “we never saw that side of him.” Punaro thinks it may be because Schlesinger considered Nunn an intellectual peer, someone who thought deeply about the issues and did his homework. It may be because Nunn also surrounded himself with equally brilliant staffers, including Punaro himself. Punaro was in his mid-30s in 1979, but he already had a lifetime of experience: a Bronze Star and Purple Heart from service in Vietnam, he was then a Marine Corps reservist with the rank of major. He also earned two master’s degrees, one in journalism from the University of Georgia and one in national security studies from Georgetown University. Punaro would eventually rise to the rank of Major General in the Marines, one of very few reservists in the history of the Marine Corps to achieve this rank. The influential Defense News consistently names him year after year one of the 100 most influential men in Washington.

Whatever the reason, Punaro told me, “Dr. Schlesinger was always willing to drop anything he was doing to help us out.” Nunn’s SALT II speech was one of those times, and I got an assignment I didn’t fully appreciate at the time: to deliver a draft of the speech to Schlesinger and not return until Schlesinger had read it given me his comments.

When I showed up at Schlesinger’s then new offices with the speech in a manila envelope, I noticed he still had boxes stacked in the corners. Schlesinger had already received a phone call from Punaro telling him I would be showing up. When I reflect back on that meeting, from a distance of 35 years, I wonder if Schlesinger – who because of his recent firing was a bit radioactive in Washington — was offended that Punaro, or Sen. Nunn himself, did not make the trip to receive Schlesinger’s advice. But if Schlesinger felt any offense, he certainly did not take it out on me. He asked me to make myself comfortable while he read the speech.

After some time, he called me into his office. I expected him simply to hand the manila envelope back to me and send me on my way. I was surprised when he asked me questions about myself. Where did I go to school? Where was I from? He even asked me about my family.

When I called Arnold Punaro to ask his recollections of those days, Punaro said he well remembered the speech and the preparations for it. “Oh, yeah,” he said. “It was a big deal.” But Punaro was not surprised by Schlesinger’s courtesy. “He was a great guy,” Punaro said. “Always friendly and personable.” Punaro said that when he was promoted to general, Schlesinger came to the ceremony. “He had long been out of government,” Punaro said. “So it was not something he had to do. It was something he did out of friendship. I was honored he was there.”

But I did not know any of this when I stood across the desk from Schlesinger in 1979, facing his questions. I didn’t know then if he genuinely cared, or if he was sizing me up. All I know is that after a couple of minutes of answering his questions he invited me to come around the desk and he went over the speech with me page-by-page. The handwritten notes on the pages were few, and they were clearly legible. But Schlesinger explained them to me as if my understanding of them mattered. He made me feel not like a delivery boy, but like a part of the process.

When I got back to Sen. Nunn’s office in the Russell Senate Office Building (named for one of those Georgia senators whose shoes Nunn was now trying to fill), I handed the speech to Arnold Punaro. He took it in to the senator. I never spoke to the Senator or to Arnold about the comments Schlesinger made. A couple of days later, Sen. Nunn delivered the speech to a nearly full house – including a packed staff gallery, where I sat with several members of Sen. Nunn’s staff. The speech got extensive media coverage, and was widely hailed as an important speech in Sen. Nunn’s own rise to be a worthy heir of Sen. Richard Russell and Rep. Carl Vinson.

The speech also had an important and long-lasting policy impact in that Nunn’s skepticism regarding the Soviets and SALT II carried the day: The Senate never ratified the treaty, and a few months later, when Ronald Reagan became president, the Democrat Nunn actively supported Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative and other programs that the Soviet Union eventually could not match. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1989, Reagan was no longer president, but Nunn was still in the Senate, as chairman of the Armed Services Committee.

I never saw James Schlesinger face-to-face again, though I did pay attention when his name appeared in the news. He never held a permanent government post again, but his influence never waned. Every American president from Reagan to Obama sought his advice. History now judges his short, tempestuous tenures at the CIA and as the head of the Department of Defense and the Department of Energy as effective and even transformational. Many projects and ideas he was almost alone in championing when he was in government became important parts of our military apparatus, including the F-16 fighter and what came to be called a “build down” of our nuclear capability, the practice of continuously improving but reducing the size of our nuclear arsenal.

One aspect of James Schlesinger’s character that did not make it into many obituaries was his Christian faith. Raised in a Jewish home, he converted to Christianity as an adult. His wife Rachel, a Lutheran from Ohio, introduced him to Reformed Protestantism, and Schlesinger turned his prodigious mind toward the study of Luther and Calvin with the same vigor he approached defense and foreign policy matters. As his Christian faith grew, his temperament mellowed. In an interview late in life with the journalist and historian Walter Issacson, he said, “I tended to be too self-righteous, a quibbler, stubborn, too. It took me a while to understand how hard I must have been to deal with.” But he did not mellow completely. Until near the end of his life, according to his protégé and former National Interest editor Adam Garfinkle, he would still occasionally refer to liberals as “ninnies who think the world is some sort of Boy Scout camp.”

He would also often talk of Rachel, who he married in 1954 and who died of cancer in 1995. “I still miss Rachel,” Schlesinger would often tell his friends. To honor Rachel, an accomplished violinist, Schlesinger donated $1-million to have the Rachel M. Schlesinger Concert Hall and Arts Center at Northern Virginia Community College named in her honor.

The funeral for James R. Schlesinger took place on April 4 at Grace Evangelical Lutheran Church in Springfield, Ohio, Rachel’s home town. He was laid to rest next to his beloved Rachel at nearby Ferncliff Cemetery. His Washington friends will honor him at a memorial service this Saturday at the Rachel M. Schlesinger Hall.

Warren Cole Smith, who lives in Charlotte, N.C., is vice president of WORLD News Group and the host of the radio program “Listening In”.

Warren Cole Smith, who lives in Charlotte, N.C., is vice president of WORLD News Group and the host of the radio program “Listening In”.