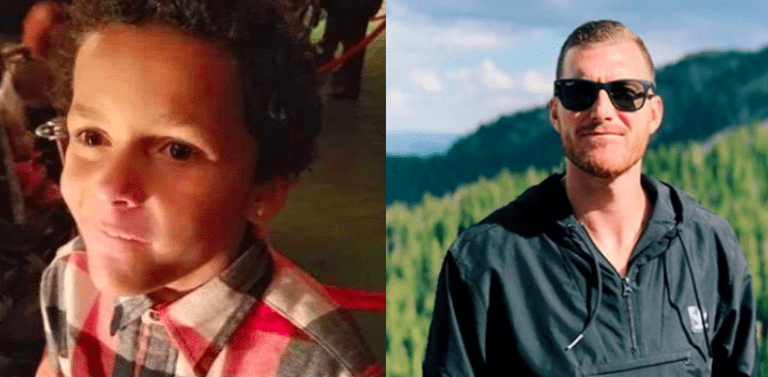

Last week, the story of a nine-year-old boy named Jamel Myles emerged across international media platforms. Jamel was an elementary school student in Colorado who took his own life after being bullied by his peers for being gay. Upon hearing Jamel’s tragic story, the nation was shocked. No person, especially a child, should be made to feel ashamed of who they are. No one should be forced to feel that their life is not worth living, especially someone as young as Jamel.

Just a few days later, another tragic story of suicide broke in the national media, this time it was Andrew Stoecklein, the lead pastor of Inland Hills Church in Chino, California. Looking from the outside, Pastor Stoecklein was leading a successful career as an evangelical megachurch pastor who was married and had four beautiful children. Yet in his own mind, Andrew was deeply suffering from depression for years but rarely talked about it in his sermons at his church. Pastor Stoecklein depression became so severe that on August 25th, he attempted suicide and after being on life support for a few days, Andrew’s life was cut short.

These two tragic stories struck me to my core because both of these victims of suicide suffered at the two intersections of my life: I am a gay man and a Christian pastor. I also have struggled with generalized anxiety disorder and depression for most of my life, and in many periods, have struggled with thoughts of suicide. As I read these stories, I could relate deeply to the pain that both of these individuals felt: my entire life has been marked with exclusion and bullying because of my feminine personality traits and my perceived sexual orientation, and I have struggled in a number of religious environments with extreme dissonance between what I truly believed and who I truly was, and the overwhelming pressure of my religious community to suppress and conform to their standards of what was right and good.

The exclusion and bullying I’ve experienced related to both of these aspects of my identity have contributed to the severity of my depression and suicidality. And clearly, my experience is not unique. Around the world, we are facing a mental health crisis with amplified levels of depression and suicide, and yet our society at large and our communities of faith are clearly not equipped to address this crisis in a way that saves lives. We have failed to fully comprehend that depression and other related illnesses are in fact, illnesses, and must be treated by health professionals.

While the details of Pastor Andrew Stoecklein’s story have rightfully remained private, it is likely that he experienced the conflict that so many people face when their faith doesn’t address or offer any consolation to their mental health struggle. Many faith communities teach that depression, anxiety, and fear are purely spiritual matters that must be addressed through spiritual practice or spiritual counseling. In many faith communities, there is still deep stigma around taking medications to help with mental health. When I first was prescribed my antidepressants as a student in Bible college, I felt tremendous shame and often heard from fellow peers that the right way to deal with my struggle was to “take my burden to God”, and trust that he would heal me.

But after years of praying and seeking spiritual guidance, my mental health wasn’t getting better. My panic attacks were increasing and so was the inner anguish I experienced. If only I would have been in a community that understood that what I was experiencing was at least partially a result of a chemical imbalance in my brain that could only be corrected with medications, I may have received treatment years earlier and shortened the intense suffering I endured throughout my teenage years.

But in order for that to have happened, my faith leaders would have needed to have been humble enough to admit that they didn’t have answers to my struggles or that the answers they did have were insufficient. It would have required my faith community to understand that mental health illnesses effect a large portion of the population and that there is no shame in experiencing neuro-divergence in whatever way that manifested in an individual. It would have required a reframing of our understanding of the human person to be more than just a body and soul, but also a physical mind that needs physical treatment when it is suffering.

But most faith communities and faith leaders aren’t willing to acknowledge this truth, and because of that, thousands of peoples suffering is amplified because they feel that their faith is somehow inadequate because they aren’t experiencing healing, and they feel fearful about pursuing non-spiritual options for treatment because they believe that their suffering is only a spiritual struggle.

In the story of Jamel, we see highlighted the tragic results of exclusion and bullying of LGBT+ people that is still all too prevalent in our world today. In my new book True Inclusion, I devote a chapter to exploring the results of exclusion on the human psyche. Looking at both psychological research on exclusion, as well as the classic Christian theology of human identity, I come to the following conclusion:

From the Christian perspective, to exclude another person from relationship, and especially relationship to God, is perhaps the most blasphemous and destructive sin we could commit. To isolate another human being is to cut them off from the relationships that are so fundamental to what it means to be a human, and degrades the very essence of their humanity.

When a person is excluded or marginalized from their classroom, peer group, family, or church, all of the evidence suggests that we are degrading their very sense of personhood and cutting them off from what Brene Brown calls “the irreducible need of all people” to belong. And the research shows that the perspective theorized in Christian theology is true: LGBT+ people who grow up in non-inclusive religious families, for instance, are five times more likely to attempt suicide than those who grow up in inclusive families. The mental illness that develops as a result of the trauma of exclusion is well documented and costs thousands of precious LGBT+ lives every year.

When my sexual orientation was revealed to my mentors in my Bible college, I was told that there was something fundamentally wrong with me and that I needed to seek God’s healing or else leave my community because my “sinful lifestyle” would not be tolerated. I was pressured into meeting with a professor who practiced a lite form of conversion therapy on me for a year, praying that God would heal and liberate me from the impulses of my gay desires. As I endured this treatment for an entire year, my internal dissonance drove me to the floor in the utility closet in my dormitory many nights begging God to take this identity away from me or else take my life away- for nothing could be worse than living as an openly gay man and being excluded from my community of faith and my calling to be a pastor.

The threat of exclusion and the anguish I felt when I wasn’t being healed of my sexuality landed me in the emergency room twice during my senior year of Bible college with severe panic attacks. Suicidal thoughts plagued my mind daily and every aspect of my social, spiritual, and physical life suffered. And on top of all of this suffering, I was too ashamed to pursue psychiatric help or to get on medication because again, I believed and was told that my anxiety and depression were an illness of spirit, not mental illness as a result of the trauma being inflicted on me by my faith community.

As my suffering was amplified to a crippling level, I finally was driven to seek out mental health professionals who identified what I was going through as an illness, who affirmed my sexual orientation as natural and good, and who offered me the therapy and medication I so desperately needed. And it was the assistance I received from psychotherapists and psychiatrists that eventually allowed me to live a healthier life, free from crippling depression and anxiety.

Nearly a decade later, I still struggle occasionally with mental illness, but I am living a much better life than I ever could have imagined back in Bible college. And it was only when I realized both the profound impact of exclusive teaching and practices in the church, and the reality and treatability of mental illness that I found this wholeness of life. I am a truly blessed person, because many people never gain access to the resources and truth that I was fortunate to find. And the gut wrenching end of many of those experiences are when we hear the stories of young Jamel and Pastor Stoecklein who suffered the loss of their lives because of exclusion and mental illness.

No one should have to suffer like these people. No one should be shamed because of who they are. No one should be made to feel inferior for seeking out mental health professionals to assist them with their mental illness. No one.

It is time for a serious change in our communities of faith and in our society. It is time that we all agree that depression and anxiety are, in fact, mental illnesses that must be addressed medically. It is time that we all acknowledge that any teaching that excludes or marginalizes based on a person’s intrinsic identity directly impacts the mental health of the person at whom it is targeted, and therefore should be understood as abusive and rejected as “false teaching”. It is time that Pastors admit that we are not trained to deal with the mental health struggles of our communities, and for churches to begin partnering with mental health professionals to meet the needs of their congregations.

If we don’t make these changes and quickly, there will be more loss and more suffering. But if we do, we will see a transformation of the health of our communities at both an individual and corporate level as more people find the help that they need and are embraced for the uniqueness of their identity- our communities will flourish and suffering will be reduced. The faith community has all too often fallen behind the wave of social change, but in this area, it is imperative that we catch up and begin leading the way. If we begin to address mental health and reject exclusion in these ways, there will be measurably less suffering, less bullying, and less exclusion in arenas of our community’s life. With a simple change in posture and teaching, we can usher in a new era of understanding that literally saves and improves lives- and isn’t that what our faith is all about anyways?

Not one more life has to be lost to suicide. Not one more person has to continue suffering at the hands of their faith community. Not one more child needs to feel ashamed of who God made them to be. Not one more. And the change begins with us.

If you are struggling with depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts, or any other form of mental health, please reach out to The Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 where there are people standing by to help you get the assistance you need.

My new book True Inclusion: Creating Communities of Radical Embrace will be released from Chalice Press on September 11, 2018. You can pre-order your copy here.