The federal government struck a blow for religious liberty this month in a Clarksburg, West Virginia courtroom. The case is fascinating and hilarious, and the winning argument has the paradoxical benefit of upholding a man’s right to a religious claim that the court’s ruling proves to be factually ludicrous.

The case also neatly disproves the absurd “Christian persecution” narrative promoted by perpetually aggrieved privileged hegemons and the hucksters who rile them up, like for example Fox News TV-talker Todd Starnes.

Matt Harvey has the story for the local paper, the Exponent Telegram, “Jury rules for worker in religious discrimination suit against Consol Energy” (via Christian Nightmares):

A federal jury Thursday [Jan. 15] ruled in favor of a general laborer at the Consol Energy/Consolidation Coal Co.’s Mannington mining operations who said he was forced to retire because of his religious beliefs.

The jury returned $150,000 in compensatory damages for Beverly R. Butcher Jr. …

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission had sued Consol Energy on behalf of Butcher. The federal agency’s filing asserted Butcher, an evangelical Christian, was told he must submit to biometric hand scanning for time and attendance tracking, even though that is against his religious beliefs. …

The jury found that Butcher “had a sincere religious belief that conflicted with an employment requirement” and that Butcher informed his employer of that belief.

The jury also found that Consol Energy failed to provide a reasonable accommodation for Butcher’s beliefs and that it wouldn’t have been an “undue hardship” to do so.

That’s a pretty good summary of the legal questions at stake. A conflict arose between employment requirements and the sincere religious beliefs of a worker. When that happens, the worker has a free-exercise right to a reasonable accommodation of their religious beliefs — provided that such an accommodation is possible without creating an undue hardship for the employer.

Note that all of these legal matters are a bit fuzzy and subjective. Questions of sincerity, reasonableness and whether or not a solution would be an “undue hardship” are not easily quantifiable. They all involve judgment — which is why cases like this often wind up in court.

But while they may be subjective, such questions have unavoidable legal significance. The trickiest of these is probably the matter of sincerity. Courts do not usually want to be the arbiters of religious sincerity — they lack the capacity and the clear jurisdiction to evaluate such a thing, and often prudently seek to avoid getting entangled in such a murky matter. Yet sincerity has a clear legal significance in cases like this.

But while they may be subjective, such questions have unavoidable legal significance. The trickiest of these is probably the matter of sincerity. Courts do not usually want to be the arbiters of religious sincerity — they lack the capacity and the clear jurisdiction to evaluate such a thing, and often prudently seek to avoid getting entangled in such a murky matter. Yet sincerity has a clear legal significance in cases like this.

Suppose, for example, that I decide I’d prefer not to work on Saturdays, and so, between bites of a cheeseburger, I inform my employer that I’ve suddenly converted to Orthodox Judaism. The EEOC wouldn’t take up my case because my religious claim would be obviously and demonstrably insincere, and my employer is not legally bound to find a reasonable accommodation for my unreasonable, insincere religious claim. Sincerity and insincerity are not always easily determined, but the point of that example is to show why such a determination is legally necessary.

In this Consol Energy case, the worker’s religious sincerity is not in dispute. Both the EEOC and the coal company mostly agree that Mr. Butcher’s religious beliefs are genuine.

Consol Energy apparently did attempt to show that Butcher’s religious beliefs were, if sincere, somewhat incoherent. But even though they were right about that, it didn’t help their case against the EEOC.

This is, for me, the fun part, because Mr. Butcher, it turns out, is an End Times, “Bible prophecy” Rapture enthusiast and a devotee of the pseudo-Christian folklore promoted by the likes of Tim LaHaye, Hal Lindsey and Jack Van Impe.

Butcher, in other words, is not so much an “evangelical Christian” as he is a devotee of anti-Antichrist-ianity. He’s obsessively worried about the Antichrist, and he balked at his employer’s use of hand-scanners because the weird, Barnum-esque folklore he’s swallowed has taught him that such devices are a tool of Nicolae Carpathia.

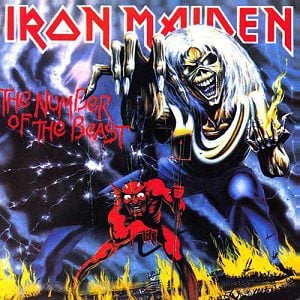

The company that makes those hand scanners, Recognition Systems Inc., seems all-too-familiar with the fear that causes anti-Antichristians to recoil from their technology. They’ve tried to engage those fears by taking these folks’ concerns seriously. Over the years, I’m sure, they’ve heard from a lot of people like Beverly Butcher or Tim LaHaye — people who say they are opposed to the use of hand-scanners because they “take the Bible literally.” And Recognition Systems recognizes that the Bible passage at issue is this one, from Revelation 13 (quoted here in the King James Version preferred by anti-Antichristians):

And I beheld another beast coming up out of the earth; and he had two horns like a lamb, and he spake as a dragon. And he exerciseth all the power of the first beast before him, and causeth the earth and them which dwell therein to worship the first beast, whose deadly wound was healed. And he doeth great wonders, so that he maketh fire come down from heaven on the earth in the sight of men, And deceiveth them that dwell on the earth by the means of those miracles which he had power to do in the sight of the beast; saying to them that dwell on the earth, that they should make an image to the beast, which had the wound by a sword, and did live. And he had power to give life unto the image of the beast, that the image of the beast should both speak, and cause that as many as would not worship the image of the beast should be killed.

And he causeth all, both small and great, rich and poor, free and bond, to receive a mark in their right hand, or in their foreheads: And that no man might buy or sell, save he that had the mark, or the name of the beast, or the number of his name.

Here is wisdom. Let him that hath understanding count the number of the beast: for it is the number of a man; and his number is Six hundred threescore and six.

Recognition Systems takes these people literally when they claim to take the Bible literally. That was the premise of the letter they provided for Consol Energy to give to poor, frightened Mr. Butcher:

Butcher’s employers handed him a letter written by the scanner’s vendor, Recognition Systems Inc., according to the lawsuit.

Addressed “To Whom it May Concern,” the letter “discussed the vendor’s interpretation of Chapter 13, Verse 16 of the Book of Revelation contained in the Bible; pointed out that the text of that verse references the Mark of the Beast only on the right hand and forehead; and suggests that persons with concerns about taking the Mark of the Beast ‘be enrolled’ (meaning, use the hand scanner) with their left hand and palm facing up,” the lawsuit asserted.

“The letter concludes by assuring the reader that the vendor’s scanner product does not, in fact, assign the Mark of the Beast,” the lawsuit asserted.

That last assurance is naively optimistic. It won’t help to reassure folks like Mr. Butcher that the hand scanner “does not, in fact, assign the Mark of the Beast,” because that’s exactly what they’d expect the Beast to say. “He deceiveth them that dwell on the earth,” after all.

Recognition Systems’ suggestion that Butcher simply scan in with his left hand is a perfectly logical response to his claim to be motivated by a “literal” reading of Revelation 13:16. But it, too, is naive — too credulously accepting that he is using the word “literal” to mean anything of the sort.

In any case, it doesn’t matter whether Recognition Systems Inc. or Tim LaHaye has the more “literal” interpretation of Revelation 13:16. The jury in Clarksburg was not being asked to adjudicate between competing interpretations of the Bible, and no jury should be asked to do that. Their task, rather, was to look at employment law — at Mr. Butcher’s rights as a worker — and to determine whether or not Consol Energy complied with that law.

And Consol Energy did not. The main problem, legally, turned out to be that the vendor’s use-your-left-hand suggestion was the only proposed accommodation that Consol Energy was willing to provide for Butcher’s religious belief (his whackily unorthodox, stupid, and laughably incoherent — but questionably sincere — religious belief).

And that was why Consol Energy lost this case. That was why Consol Energy deserved to lose. They broke the law.

Religious liberty, if it is ever to mean anything at all, must include the freedom to be wrong. It cannot matter, legally, whether or not a religious belief is orthodox, or coherent, or part of a longstanding established tradition. Protecting religious liberty means protecting the right to believe in the implausible, the idiosyncratic, the offensive, the stupid, the factually insupportable, the demonstrably false. Otherwise we’d wind up putting the state in the position of adjudicating between legitimate and illegitimate religious beliefs.

And that, we should have learned by now, never ends well. That’s a recipe for inquisitions and for sectarian violence. That reduces religious liberty from an inviolable human right to a privilege contingent on the religious perspective of the current regime.

Beverly R. Butcher Jr. is wrong. And he has every right to be wrong — even to be ludicrously wrong, as he is. Defending religious liberty means we have to defend the right of people like him — or like Tim LaHaye, or Ken Ham, or Cindy Jacobs, or Tom Cruise, or David Green — to be ludicrously, offensively, exuberantly wrong.*

So the absurdity, stupidity and foolishness of Butcher’s religious beliefs can have no bearing on his legal right to a reasonable accommodation. Such an accommodation should have been easy for Consol Energy to provide, but they refused to do so:

Company officials rejected Butcher’s counter offer to either keep a written record of his hours, as he had been doing, or to check in and check out with his supervisor, the lawsuit contended.

At many different jobs, I’ve checked in and out using old-fashioned punch-card time clocks, digital time clocks, written time sheets, and informal nods to the boss. I’ve never used a hand scanner. Most people haven’t. Most companies haven’t. So allowing Butcher to clock in using any of those other methods surely wouldn’t have been an “undue hardship” for the company.

That’s why the EEOC won this case for Butcher and why Consol Energy lost.

But consider the delicious irony of what that outcome means for the content of Mr. Butcher’s religious claim. The good guys here — the advocates defending his case — were the feds. And the feds actions here proved that the existence of hand-scanner technology does not mean that “no man might buy or sell, save he that had the mark, or the name of the beast, or the number of his name.”

By winning his case, the EEOC proved that the substance of Butcher’s religious claim — his “Bible prophecy” religious objection to hand-scanners — was nonsense. By defending his religious liberty, the EEOC proved that the content of his religious claim was false.

The EEOC just proved that Beverly R. Butcher Jr.’s religious beliefs are wrong — and that he has the right to be wrong.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* Note, however, that the right to be absolutely wrong does not entail an absolute right to force others to agree or to comply with you. Every belief, no matter how obviously wrong, has the right to a “reasonable accommodation,” but not to an unreasonable accommodation. Everyone has the right to be wrong, but we do not have the right to create an undue hardship for everyone else.

Thus, for example, as a Scientologist, Tom Cruise has every right to refuse psychological and psychiatric care, and we can reasonably accommodate his religious liberty on that point. But accommodating Tom Cruise does not mean that health insurers cannot be allowed or required to insure psychiatric care for everyone else.

Similarly, David Green is a devout anti-abortionist. That’s his religion — a religion even more dubious than Scientology in that it includes the factually untrue dogma that equates contraception with abortion. Green’s religion may be loopy and dumb, and it may be dependent on false claims about human biology, but he has every right to be so utterly, demonstrably wrong. His sincere foolishness, like Cruise’s, should be afforded reasonable accommodation.

But, just like Cruise, Green does not therefore have the right to create an undue hardship for everyone else. He does not have the right to require others to be wrong as well. Just as Scientologists do not have the religious liberty to prohibit everyone else from having psychiatric care or insurance for such care, so too anti-abortionists do not have the religious liberty to prohibit everyone else from using contraception or from insurance that covers it. That’s why the Hobby Lobby decision was incorrect — why it makes about as much sense, legally, as Cruise’s ideas about Xenu and Dianetics.