Beverly Engel writes that a meaningful apology “communicates … the three R’s — regret, responsibility, and remedy”:

1. A statement of regret for having caused the inconvenience, hurt or damage. This includes an expression of empathy toward the other person, including an acknowledgement of the inconvenience, hurt, or damage that you caused the other person. …

2. An acceptance of responsibility for your actions. This means not blaming anyone else for what you did and not making excuses for your actions but instead accepting full responsibility for what you did and for the consequences of your actions.

3. A statement of your willingness to take some action to remedy the situation — either by promising to not repeat your action, a promise to work toward not making the same mistake again, a statement as to how you are going to remedy the situation … or by making restitution for the damages you caused.

Aaron Lazare, similarly, outlines what he says are the “up to four parts to an effective apology“:

1. A valid acknowledgment of the offense that makes clear who the offender is and who is the offended. The offender must clearly and completely acknowledge the offense.

2. An effective explanation, which shows an offense was neither intentional nor personal, and is unlikely to recur.

3. Expressions of remorse, shame, and humility, which show that the offender recognizes the suffering of the offended.

4. A reparation of some kind, in the form of a real or symbolic compensation for the offender’s transgression.

I think both of those outline the essential, necessary components of any meaningful apology — one that can be described as genuine, worthy of being offered, and capable of being accepted.

And both models show us, clearly I think, that neither “Thank you for your service,” nor “Happy Veterans Day” comes close to satisfying those criteria. These ritual statements are inadequate and unsatisfying apologies — partly due to the fact that we repeat them without ever quite acknowledging that they have anything to do with the attempt, and the need, to apologize.

The parades and flag-waving and all the rest are legitimate and necessary expressions of gratitude, but they are also attempts to skip ahead to what Engel calls “remedy” and Lazare calls “symbolic compensation.” The gratitude they attempt to convey is thus undermined by the reminder that regret and responsibility may never be explored, discussed or acknowledged.

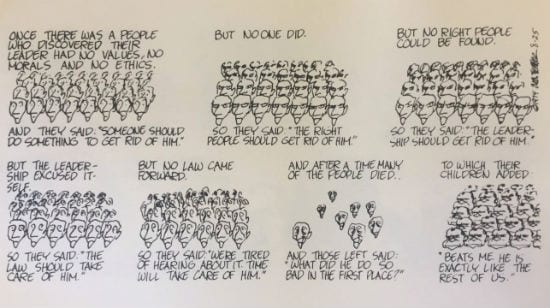

That failure to express, or even consider, regret and responsibility also prevents us from providing another essential element to any meaningful apology: The pledge not to do it again.

And again, and again, and again.

We can’t offer such a promise because we’re going to do it again. We’re still doing it now. And we have no intention of stopping.