I post this analysis at the risk of being completely ignorant. I mean that in a humble sense–as I seek to learn to care about the welfare of all people. Speaking of an oppressed culture, as one who lacks the ability to fully understand, is a risk. I post this reflection as part of my journey of understanding the African American struggle. This reflection focuses on an essay by African-American feminist scholar Delores Williams. Her essay moved me. I welcome insights. Please know that I’m aware of the fact that my blindspots are broad.

I post this analysis at the risk of being completely ignorant. I mean that in a humble sense–as I seek to learn to care about the welfare of all people. Speaking of an oppressed culture, as one who lacks the ability to fully understand, is a risk. I post this reflection as part of my journey of understanding the African American struggle. This reflection focuses on an essay by African-American feminist scholar Delores Williams. Her essay moved me. I welcome insights. Please know that I’m aware of the fact that my blindspots are broad.

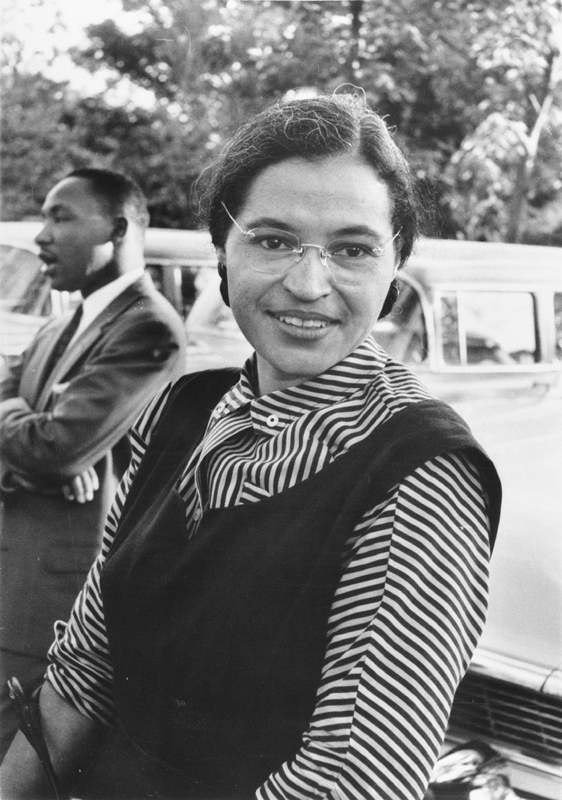

Anyone who grew up in the years following the Civil Rights Movement knows the story of Rosa Parks. This woman embodied a posture of dignity and resistance. Her iconic refusal to give up her seat on a bus for a white person gave inspirational fuel to the movement. As a woman—a black woman—she took up a call for justice by asserting both her female and black identity.

In Sisters in the Wilderness: The Challenge of Womanist God-Talk, Delores Williams states that “the modern phenomenon of black mothers like Rosa Parks acting as catalysts for social change stems from a long tradition of black mothers and nurturers who were catalysts for social change in and beyond the African-American community—even though some social processes in the community restricted black women’s opportunities while expanding black men’s opportunities” (543). In other words, according to Williams, a long tradition of black women asserting themselves—even when socially powerless—created the conditions from whence resistance was made possible. It is to this tradition that I will to focus in this response essay.

Delores Williams begins by anecdotally helping readers understand why a womanist approach to the African American narrative intrigues her. After being frustrated by the lack of female voices in the African American theological tradition, she began excavating various historical and literary sources, from a womanist perspective, to uncover the centrality of the black woman in the tradition. Before I go on to explore some of her findings, the lack of female resources for inquiry into the past raises an important issue. I’ve heard it said that history is not the study of the past, but rather it is the study of how things were remembered and why.[1]

One thing to note is how patriarchy controls the way we remember the past, in virtually every culture in human history. Much of our so-called histories come from the perspectives of the victors, the ones in power, and not from the social class who experienced “life on the ground.” This tendency exists even in the African American tradition, but fortunately not to the point that we cannot salvage resources for seeing the ways in which oppressed women maintained their dignity.

Williams’ discussion helps us to see how the African American community appropriated the Scriptures to make meaning out of their experience of slavery and oppression. Surprisingly the Exodus is scarcely mentioned, mostly as this is not her area of focus. She notes that in liberation theology that the “validating biblical paradigm in the Hebrew testament was the exodus event…. [and in the] Christian testament [their] paradigm was Luke 4, when Jesus described his mission and ministry in terms of liberation… [with] their normative claim for biblical interpretation… [of] ‘God the liberator of the poor and oppressed” (531).

I was a bit surprised by her choice to nearly disregard this theme as a resource. It seemed, at first, that even the womanist can find helpful resources in the experiences of post-Egypt women who play a role (albeit minor) in their journey to the Promised Land. Liberation from a God who “hears the cry” of the oppressed certainly offers hope to both the oppressed woman and man alike. What becomes apparent is that Williams’ interest is not in liberation per se (at least not in the essay I read), but in the “mammies” who asserted themselves and maintained their dignity through their faith in a God who valued them as human image-bearers. As Williams makes clear: “[T]he African-American mother’s God-consciousness and absolute dependence upon God provided hope… where hope seemed absurd.” This view of God provided resources for their own self-image and empowerment to at times defy “laws and custom in order to nurture black people with care and compassion” (542). “Mammies” were empowered through their own self-worth, even when the hope of liberation was distant. They were strong right where they were planted. That fact should inspire us all.

Williams chooses to focus on a different theme that still helps build her case: that of Hagar, the slave cast out as a single mother of Ishmael. This story does not, in the author’s opinion, belong “to the liberation tradition of African-American biblical appropriation” (532). In many ways, Hagar’s story is not one of liberation by God, but of her taking up her own cause of freedom from her oppressive masters with God being a resource for her own efforts of survival. Her approach, then, is a “survival/quality-of-life tradition of the African-American biblical appropriation” (534). She credits, for instance, the “mammy” within slavocracy as the strong mothers of the community who utilized the Christian tradition as a source for maintaining dignity even as she was systematically raped and bred by slave owners.

At one moment as I read this essay, I was nearly moved to tears in the middle of Starbucks. As a white male I have no idea what it is like to struggle with dignity in this way. About “mammy,” Williams states: “But it must be emphasized that strength is not necessarily synonymous with power, nor does it here imply an idea of black matriarchy…. The antebellum black mother had no real power… many… had the helpmate not of the black man but black religion” (536-537). I have no real experience of lacking power in this way. Therefore, I may never know this sort of “strength.” This is a similar strength, I assume, that Rosa Parks utilized generations after slavery as she asserted the dignity of black women in the modern world. Thank God for the strong “Mammies” of the African-American story.

————————-

[1] This insight comes from, Historical Jesus: What Can We Know and How Can We Know It? by Anthony LeDonne (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2011).

****Page Numbers Correlate to this book: Theory and Method in the Study of Religion: A Selection of Critical Readings