(At least once every two months, I plan to take a break from reviewing new releases and analyze a past masterpiece. Sometimes it will be a movie from decades ago, sometimes a more recent film.)

If you asked a dozen film historians to name a great humanist director, I’d bet a hundred bucks that for at least half of them, the first name off their lips would be Akira Kurosawa. In his fifty year directing career (1943-93), Kurosawa unflinchingly tackled life’s biggest questions: the purpose of individual and communal life, the existence of God, the moral responsibility of leaders, and the value of tradition versus change, to name just a few. He immeasurably enriched world cinema by living up to his motto: “To be an artist is to never avert your eyes.”

Although the Japanese sensei sometimes got a little preachy, his sermonizing rarely interfered with engrossing storytelling, contagious passion, and lush characterization. Additionally, Kurosawa was a stylistic innovator. He deftly combined sound and image to multiply his tales’ emotional impact, employed brisk editing and abrupt transitions to push his narratives along, and sharply framed his images in a manner consistent with his painter’s education. A later generation of American filmmakers – including Scorsese, Francis Coppola, Spielberg, and Lucas – put these techniques to work in their own movies (and even repaid their artistic debt to the master by helping subsidize the making of his final movies).

In reviewing his remarkably consistent catalog of 30 films, at least ten of them are undisputable masterpieces (and only one is a flat out dud). The crème de la crème includes his action epic Seven Samurai (far superior to the American remake The Magnificent Seven), the comically cynical Yojimbo (blatantly plagiarized by Sergio Leone in his Clint Eastwood spaghetti western For a Fistful of Dollars), the gripping kidnapping drama High and Low, and the despairing yet colorful late film Ran (his reworking of Shakespeare’s King Lear).

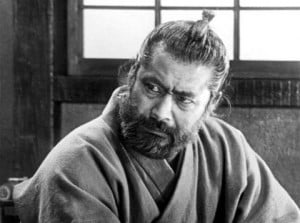

I’ve chosen to scrutinize Red Beard for a couple of reasons. First, as a coming of age tale about an unformed, naive medical doctor, the film powerfully resonates for me as a physician. More significantly, though, Red Beard marked the end of an era for Kurosawa. This was the last film he made with his longtime leading man Toshiro Mifune, arguably the greatest actor Japan has produced. Red Beard was Kurosawa’s final black and white film, and the last of his nineteen postwar movies that as a group strongly extolled an individual’s duty to effect societal transformation. Kurosawa’s color films of the ‘70’s and ‘80’s, by contrast, were garish but bleak.

Like many Kurosawa films, Red Beard, set in still-feudal Japan, centers on a mentoring relationship. In this case, the film opens with young Doctor Yasumoto (Yuzo Kayama) arriving at the clinic and hospital of Doctor Niide (Toshiro Mifune), nicknamed Red Beard. Yasumoto, a member of the samurai class, indignantly believes that the destitute patients and austere setup of Niide’s clinic are well beneath his station. Initially, he refuses to work and instead makes a nuisance of himself, hoping that Niide will fire him. Only his own near brush with death and witnessing the demise of two virtuous older men begin to awaken him to his duty to serve all humanity, rich or poor.

So, what exactly makes Red Beard a masterpiece? I will underscore five reasons for designating it a timeless classic.

First, akin to his favorite author Dostoevsky, Kurosawa’s narrative features brilliantly interlocking and contrasting characters. When Yasumoto first shows up to the clinic, he is shown around by a departing young doctor who can’t be bothered to hide his contempt for the impoverished patients treated free of charge by Niide. Ironically set against stirring images of the suffering masses (highly reminiscent of Daumier’s classic prints of the French downtrodden), this physician loudly declaims that these folks would be better off dead. Yasumoto, on the other hand, commendably demonstrates a willingness to change his attitude and mend his behavior towards Niide, his staff, and the sick under his care.

The other major opposites are two female patients at the clinic, “the Mantis” and Otoyo. We learn that both of these young women suffered horrific trauma, some of it sexual in nature. The Mantis, so completely defined by her lethal behavior that we never learn her birth name, has seduced and murdered three men in the past, such that she must be kept under constant lock and key.

Contrarily, twelve-year-old Otoyo, rescued from a brothel when deliriously ill, elects to follow the virtuous path of aiding those who are equally needy. Niide empathically instructs Yasumoto that many women have been traumatized like the Mantis and Otoyo, yet such victims still possess freedom to choose their ultimate response to hurtful experiences.

A second key to Red Beard’s greatness is Kurosawa’s skilled representation of Niide’s clinic as a safe haven. The film opens with a melody intentionally reminiscent of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, that great ode to universal brotherhood. Meanwhile, the initial credits play against a visual background of the clinic’s rooftops, signifying the healing shelter to be found there.

As the film progresses, we further observe the visual harmony of the clinic. Its pillars, halls, and latticework soothe with their straight lines and right angles. This is in stark opposition to the world outside, which is broken, twisted, disaster-prone, and windswept.

Third, the film persuasively rails against poverty and ignorance as the true source of sickness. (Funny how this hasn’t changed, 150 years later and across the Pacific Ocean, where over half of U.S. health costs can be chalked up to alcohol, tobacco, obesity, and undertreated illnesses that blossom into far worse conditions.)

Ex-Marxist that he was, Kurosawa cleverly proposes a remedy to society’s economic inequality through the visual symbolism of Yasumoto and Otoyo’s clothing. When Yasumoto first arrives at the clinic, he stubbornly refuses to shed his lavish samurai garb. Only as he buys into Niide’s ethos does he don the simple uniform worn by all of the clinic doctors.

Otoyo conversely graduates to finer attire. In her ill state, she is carried to the hospital in ratty, tattered clothing. Clinging to her past like Yasumoto, she initially refuses to surrender these garments, but when she chooses to make the hospital her home, she simultaneously accepts a fine kimono given to her by a friend of Yasumoto.

Fourth, Kurosawa maintained a stable of topnotch actors, from whom he consistently elicited excellent performances, and Red Beard is no exception to this rule. Toshiro Mifune could always be counted upon to fully step into the roles created for him by Kurosawa, whether an impoverished wannabe warrior (Seven Samurai), a tubercular gangster (Drunken Angel), a businessman descending into madness (Record of a Living Being), or a neurotically insecure detective (Stray Dog). Here again, Mifune doesn’t disappoint, as the tireless paragon whose gruffness cannot conceal a tender heart broken by the incomprehensible misery around him.

Yuzo Kayama may have been a Japanese heartthrob when he took on the role of Yasumoto, but he, too, brings substance, depth, and plausibility to his impassioned reactions to the events around him. Equally winning are the skilled portrayals by supporting actors. For instance, Tsutomu Yamazaki made viewers’ skin crawl two years previously as an icy killer in High and Low. Here, he compellingly plays Sahachi, a terminally ill handyman doomed in his love for a woman already trapped in a family-arranged engagement. Actress Haruko Sugimara was better known for playing middle class busybodies in the domestic dramas directed by Kurosawa’s contemporary Yasujiro Ozu, but in Red Beard, she utterly convinces as a loathsome madam who oozes insincere charm in her fight to reclaim young Otoyo for her brothel.

A crucial fifth reason for this film’s masterpiece status is Kurosawa’s manifold visual expertise. The widescreen format has seldom been better and more generously used than in Red Beard. When the deadly Mantis stalks Doctor Yasumoto, they initially face off at opposing ends of the screen, with the gap steadily narrowing during her slow, suspense-filled seduction.

A later scene, in which Otoyo strives to aid a proud malnourished urchin named Chobo, could serve as a study for perfection in framing and execution. The action unfolds in a field where hospital quilts are hanging up to dry, so Otoyo and Chobo intermittently appear and disappear behind the laundry, or only their hands are visible, as each offers the other a gift of food.

Kurosawa ingeniously utilizes the varied shadings of black and white, too. As the doctors dine together in the evening, their figures and the shadows behind them create a lovely symmetry. In another scene, moonlight striking fence rails and steps as Sahachi meets his lady, with only a small tinkling bell for sonic accompaniment, produces a dreamlike effect.

I’d like to conclude on a personal note. Early in the film, Niide imparts this piece of wisdom to Yasumoto: “There is always some story of great misfortune behind illness.” In my medical role, these words have become a mantra for me. They serve as a fine reminder of the human aspect of physical adversity, which can easily get lost in busyness, suffocating bureaucracy, or the reductive temptation to see patients as a mere collection of symptoms.

However, Kurosawa’s urging of humanistic compassion is a universal message, most definitely not for health care workers only. In one of Red Beard’s climactic sequences, the doctors gather around a gravely ill child, forming a semicircle. The camera, and by extension the viewers, close the remaining 180 degrees. It’s as if Kurosawa is asking us all, “Will you lend a hand, too?”

5 out of 5 stars

(Parent’s guide: Red Beard is unrated, but contains mature subject matter, some violence, and a medically graphic scene or two. I consider it suitable for teens, but not for younger children