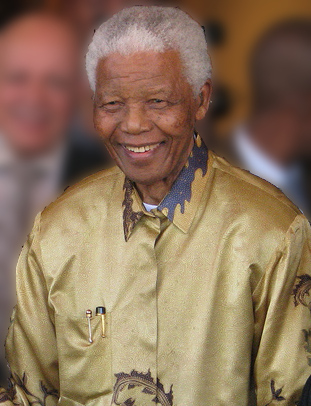

On July 18th, Nelson Mandela Day took place as people from all walks of life celebrated the work of the former political prisoner and Black freedom fighter:Nelson Mandela.

Mandela struggled against the apartheid regime, which made life for everyday Black people unbearable. Apartheid South Africa ostracized indigenous populations from power and control of their destinies, confined Blacks to a tiny landmass in desolate homes, barred Blacks from a decent livelihood, established an asymmetrical relationship of exploitation and subservience, and, in turn, produced wretched social conditions for Blacks.

As this oppression and tyranny took place, Islamic scholars of that era and land turned a blind eye, refusing to support resistance to the unjust regime that inflicted heinous atrocities against Blacks. According to Religion and the Political Imagination in a Changing South Africa by Professor Eve Mullen, the Muslim Judicial Council of South Africa declared:

The Muslim Judicial System (which represented the opinions of the ulema or Islamic scholars of South Africa) took the cowardly stance that so long as their ability to practice the rituals of Islam were not threatened, resistance was unnecessary and they remained passive as Black people suffered. One notable exception to this was Imam Abdullah Haron. His political awakening came when he was inspired to bring Islam to Black migrant laborers and became appalled by the conditions the apartheid government imposed upon Black people.

Shunning political correctness of the time, he urged resistance against the apartheid regime in his khutbas and sharply criticized the indifference of Muslims to apartheid. Imam Haron’s principled political stances resulted in him being shunned and he was widely considered an embarrassment. Imam Haron would state, “The Muslims have a revolutionary prophet but the Muslims are still asleep.”

Convicted in his stance, Imam Haron reached out and built bridges with Black communities and liberation movements, such as the African National Congress and Pan-African Congress. His stance according to Ursula Gunther represented, “A break with the ulama’s hegemony.” Soon, Imam Haron became a member of the Pan African Congress and was, “dedicated to the overthrow of apartheid by all means at its disposal, including violence.” Just like Nelson Mandela, Imam Haron was arrested under the Terrorism Act of 1967.

The Muslim Betrayal of Imam Abdullah Haron

Imam Haron was subjected to immense torture by security forces of the apartheid government which included electric shock to his genitals and needles placed in his spinal cord. Even under torture, he refused to release information and was eventually assassinated by the apartheid government security forces.

As a result of him being classified as an embarrassment to the ulama of his day, “Haron was virtually forgotten by Muslims.” Even further, “The Imam’s death did not politically ‘awaken’ the Muslim community but rather drove them into further submission of oppression…” Muslim organizations which Imam Haron formerly affiliated with were more concerned about “public relations”, securing their reputation and distancing themselves from Imam Haron than they were about condemning apartheid.

In light of this cowardly betrayal of Imam Haron, the question then becomes how can Muslims and humanity in general best honor his legacy? I posit that it can only be properly done by recognizing the myth of a post-apartheid South Africa and continuing the struggle against global white supremacy.

The Myth of Post Apartheid South Africa

In Kaffir Boy: The True Story of a Black Youth’s Coming of Age in Apartheid South Africa author Mathabane explains the laws that criminalized unemployed blacks. They were abolished with the fall of legalized racism, but they had a powerful influence while they were in effect. Mathabane’s father was fired from his job and began searching for a new one, when the police discovered him and arrested him due to his unemployment status.

His time spent in jail included strenuous work, and upon his release, “He spent days telling my mother…about the thousands of Black men locked inside simply because they, like he, had committed the unpardonable crime of being unemployed.” Such laws, criminalizing Black unemployment have been removed, but even after apartheid, we can see that three factors are directly linked: unemployment, poverty, and incarceration.

Furthermore in Not Separate, Not Equal: Poverty and Inequality in Post-Apartheid South Africa, the authors Hoovegeen reports that 68% of Africans lived in poverty, while poverty was virtually non-existent for whites; poverty continues to disproportionately impact the indigenous African population.

They further discovered that in every area of society from health to housing, Blacks significantly lag behind whites, and even when it comes to access to water, Ozlernotes that “only a quarter of Africans had access to piped water in their houses, while whites had universal access.

The problems of poverty continue today. In 2014, 45% of Black women and 35% of Black men were unemployed, whereas only 22% of white women and 14% of white men were unemployed. Thus, while formal legal racism criminalizing Black unemployment no longer exists, the vast unemployment rate of Blacks still feeds the prison system.

In a study titled Racism and Discrimination in the South African Penal System – by Dissel and Kollapen, they found that the vast unemployment rate of Blacks led to an escalated crime rate; their conclusion was, “Black people will continue to be imprisoned simply because they are poor.” This vestige of white supremacy (mass incarceration of Blacks) is still covertly and unconsciously being practiced today, though there are no explicit laws that contribute to such racism.

We can also see how the end of formal legal racism did not rectify the damage dealt in the case of the Native Land Act, which confined the indigenous African population to less than 7% of South Africa’s landmass, and gave the most fertile land to the white minority.

This inequality remains today: In a 2013 study, Cherryl Walker and Alex Dubb determined that “whites as a social category still own most of the country’s land.” According to the census, only 8.9% of South Africa’s population is white, whereas 79.2% of the population is black.

South Africa is still in a state of apartheid, just a neo-apartheid in which blacks appear to be ruling politically but white supremacy is solidified through more subtle means. The fact that a white minority owns the majority of the land in South Africa is indicative of ensuring defacto racism that still exists within South Africa.

Keep the Struggle of Imam Haron Alive!

In Towards a Post-Apartheid Critical Race Jurisprudence: Diving Our Racial Themes, Joel M. Modiri, puts forth the argument that the end of formal legalized racism did not at all end white supremacy; rather, he indicates that “white racism and the operation of white privilege have had to change in mondus operandi, and have become more subtle, covert and unconsciously practiced.” We should use Mandela Day and the Memory of Imam Haron to honor them by devoting ourselves to ending this neo-apartheid which still exist in South Africa.