Ilana Yurkiewicz explained, as a doctor, how she has to make an active effort to avoid learning callousness from the occasional deceptions of her patients. Meanwhile, in the Federalist, Teresa Mull is tackling a similar problem in modern dating. She’s worried about the danger of being emotionally overextended, and would like to see folks engage in fewer high-turnover, emotionally-intense assignations.

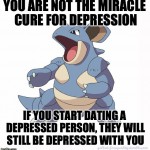

The practice of bonding and staying close until one partner arbitrarily changes his or her mind is detrimental to both physical and emotional well-being. And what doesn’t kill you makes you jaded.

While I admit that a broken heart or two along the way is inevitable, the way we respond to repeated disappointment has its own negative ramifications. We end up giving increasingly less of ourselves to each subsequent relationship to avoid another agonizing emotional roller-coaster. The piece of tape that is our emotional attachment gets less and less sticky each time it’s ripped off.

We’re left never really trusting, never really fulfilled, and never really happy. We lower the bar and settle for matches that are “good enough” but not truly satisfying because we come to value stability over idealism.

I have some sympathy for her position. I wound up deleting my OkCupid profile during a period of singleness simply because I was getting grumpy-in-advance when I had a new message notification–before I’d even read it!–because such a high percentage had been frustrating/stupid. If I wasn’t capable of opening a new message in a pleasant frame of mind, I thought it was better to shut down my inbox, until I came up with a fix to try out. And, in the meantime, I’d look elsewhere.

Mull’s problem isn’t so easily solved. She’s not objecting to one particular venue for modern dating, but to the whole kit-and-kaboodle. Her focus is mostly on encouraging emotional chastity–being more careful not to give away your heart so many times that you don’t have any of it left. I think there’s more potential in rejiggering how we approach “failed” relationships and the attendant grief, than in just trying to stay below some subcritical threshhold.

Mull’s article reminded me of some discussion I’ve seen of the drawbacks to our “Relationship Escalator” approach to romantic relationships:

Relationship escalator: The default set of societal expectations for the proper conduct of intimate relationships. Progressive steps with clearly visible markers and a presumed structural goal of permanently monogamous (sexually and romantically exclusive), cohabitating marriage — legally sanctioned if possible. The social standard by which most people gauge whether a developing intimate relationship is significant, “serious,” good, healthy, committed or worth pursuing or continuing.

There’s an element of truth to the escalator model — the Catholic view of sexuality is that it is ultimately directed toward marriage, but that’s not quite the same thing saying every romantically-charged relationship you enter is directed toward marriage–otherwise we’d marry the first person we went out. Instead, relationships are supposed to be subject to discernment, in which both people decide whether to get off the escalator entirely, or keep going, or maybe more back a step for a little while, or rest where you are.

None of these outcomes are “failures” of a relationship. Adopting a discernment-focused model for relationships means that correctly ending a relationship is a successful conclusion to the romance (which was not necessarily a mistake to begin). And it means that relationships are kiboshed by more than just a failure to make each other happy, or any kind of last-straw condition.

If you’re dating to screen for marriage, then, most of the time the problem won’t be a fatal flaw in your beloved (or, hopefully, in you), but some problem that occurs due to the conjunction of the two of you — one that wouldn’t even be an issue if you paired with someone else. Some examples: timing of when you plan to get married/have kids (often due to career constraints–sorry STEM post-docs!), plans about where to live, philosophical/religious differences, etc.

None of these are character flaws, but all might be sufficient to, even though you both like each other, to stop wheel-spinning and waiting for an acute, near-term problem to make the split inevitable. If you only break up when the relationship becomes impossible to live with now, it’s not surprising that those breakups are particularly painful.

When we expect most relationships to end well by, well, ending, it’s much more plausible that the former inamoratas might end up friends, still willing each others goods and delighting in each other, but in a new context, one that’s better ordered to the long-term happiness of them both. But it’s a lot easier to ride out the relationship-transition turbulence if our society gives us more scripts for stepping off the escalator without stepping away from a person we still like and care about.

Finally, though, it’s important to still consider Yurkiewicz’s solution, applied to this new problem. Sometimes the “fix” for pain/being taken advantage of is just thinking a little more about what tradeoff, exactly, you’d need to make to be “safe.” And, even if you do wind up deciding to shift your spot on the vulnerability-safety spectrum toward the “security” side, you’ll still to plan for how to be kind to yourself and others when unpleasantly surprised.