In 2015, I’m reading and blogging through Ronald Knox’s collection of sermons on Christian exemplars, Captive Flames: On Selected Saints and Christian Heroes. Every Monday, I’ll be writing about the next portrait in the book, so you’re welcome to peruse them all and/or read along.

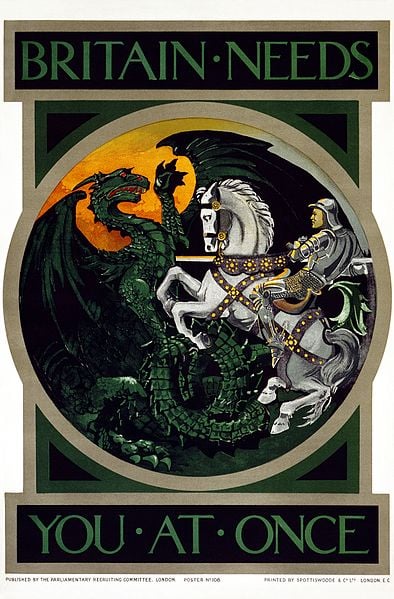

In his sermon on St. George, Knox focuses primarily on why England would choose this saint as its patron, and what this reflects about England itself. It makes sense that Knox looks past the saint at what the choice of him reflects, since, as he points out in his remarks, this is a saint whom we honor, but about whom we know almost nothing. Knox uses the rallying cry “St George for merry England!” as his jumping off point for instruction:

That word ‘merry’ is not so simple as it sounds. It is a difficult word, for example, to translate into any foreign language. It is typical of our modern conditions that hardly ever use it nowadays, except when we call a person ‘merry,’ meaning that he was slightly drunk. It survives, chiefly, in old fashioned formulas such as Merry England, or a Merry Christmas. Merry does not mean drunk, or uproarious, or frivolous. It means that a man is light-hearted, that his mind is at ease, that he is in a good humour, that he is ready to share a bit of fun with his neighbours. There is humility in the word, and innocence, and comradeship. And such a frame of mind as that is not to be secured, by grown-up people, through a continuous whirl of excitements, or a long course of dissipations. It comes from within.

Knox is still correct; I almost never hear the word “merry” apart from “old England” or “Christmas.” I can’t think, off-hand of any time I’ve heard it applied to a person (possibly Dumbledore has merry eyes at some point?). If I want to think of the virtue Knox is describing, I think I most often see it described, in secular and religious sources, as “lightness.”

From G.K. Chesterton’s Orthodoxy:

In perfect force there is a kind of frivolity, an airiness that can maintain itself in the air. Modern investigators of miraculous history have solemnly admitted that a characteristic of the great saints is their power of “levitation.” They might go further; a characteristic of the great saints is their power of levity. Angels can fly because they can take themselves lightly. This has been always the instinct of Christendom, and especially the instinct of Christian art. Remember how Fra Angelico represented all his angels, not only as birds, but almost as butterflies. Remember how the most earnest mediaeval art was full of light and fluttering draperies, of quick and capering feet.

From Eliezer Yudkowsky’s “Twelve Virtues of Rationality”

The third virtue is lightness. Let the winds of evidence blow you about as though you are a leaf, with no direction of your own. Beware lest you fight a rearguard retreat against the evidence, grudgingly conceding each foot of ground only when forced, feeling cheated. Surrender to the truth as quickly as you can. Do this the instant you realize what you are resisting; the instant you can see from which quarter the winds of evidence are blowing against you. Be faithless to your cause and betray it to a stronger enemy. If you regard evidence as a constraint and seek to free yourself, you sell yourself into the chains of your whims.

Merriness and lightness seem to be the moral and epistemological analogue to the “ready position” we had to assume in gym (weight over the balls of your feet, knees slightly bent, feet shoulder width apart). The aim was to be ready to move swiftly and smoothly, in the manner of Chesterton’s angels. Knox is describing the tempermental way we can prepare ourself to offer and share joy, not as a planned, premeditated act, but as the natural response to the opportunities that present themselves to us, as we live alongside others.

I tried to think about when I feel lightest or merriest, since although I try to offer joy and hospitality to others, it’s frequently within the safety of structure and scheduling. The closest I’ve probably come to Chestertonian levity in the last few months was when I babysat a friend’s two year old for a whole weekend. When we walked to the farmer’s market, or to the playground, I was without a deadline (for once).

I had no reason to hurry my charge along — if she wanted to look at pebbles by the sidewalk for ten minutes, that was fine; we had no commitments to anyone else that we needed to keep. I could respond lightly and merrily to whatever came up, throwing myself into going down a slide with her, until she wanted to dig in the dirt, and I sat on the bench, ready to be called on.

I got to cheat, a little — knowing I was babysitting, I cleared my calendar of all other commitments (a temporary luxury not available to actual parents). I made space for levity by subtracting other obligations and connections. I don’t think that solution generalizes very well, if I want to be able to make and keep standing commitments to other people.

But, if there were anywhere it would make sense to develop this temperament, whatever the costs of clearing time and space, it would probably be in my prayer life. I don’t feel as patient or as balls-of-my-feet ready in prayer as I do with a child. My ease-of-responsiveness feels much more strained when I’m trying to follow God, instead of a two year old.

As I look toward Lent (beginning next week), I’d like to think about preparing for Easter by cultivating the merry lightness that Knox praises, so that I have to opportunity to move quickly and joyfully in response to God.