In Horses of the Dark Time, I explored some of the horse mumming customs which happen toward the end of October in Britain. But most of these frisky, yet mysterious, skull horses make their appearance over the Christmas and New Year season. Lots of people are familiar with the Welsh Mari Lwyd, and you can read about her here, but there’s more to these traditions than just her, so much more, and I love them all!

We have a poor owd horse

And he’s standing at your door,

And if you wish to let in

He’ll please you all I’m sure.

Poor owd horse, poor owd horse.

He once was a young horse

And in his youthful prime;

His master used to ride on him

And thought him very fine

But now he’s getting owd

And his nature doth decay,

He’s forced to nab yon short grass

That grows beneath yon way.

We’ll whip him, hunt him, slash him

And a-hunting let him go,

Over hedges, over ditches,

Over fancy gates and stiles.

I’ll ride him to the huntsman;

So freely I will give

My body to the hounds then,

I’d rather die than live.

Poor owd horse, poor owd horse.

So goes the song of one of Britain’s house-visiting traditions involving dead horses at Midwinter. The tradition of the Old Horse is mostly found in the area around Sheffield, South Yorkshire, including bits of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. The tradition can only be proven to go back to the mid-19th century in this form, but how old is it really? Nobody knows. The church’s Council of Auxerre (circa 578 AD) states that “It is forbidden to masquerade as a bull-calf or stag on the first of January.” A hundred years later the Archbishop of Canterbury expanded the theme in his Liber Penitentialis:

“If anyone at the Kalends of January goes about as a stag or a bull; that is, making himself into a wild animal and dressing in the skin of a herd animal, and putting on the heads of beasts; those who in such wise transform themselves into the appearance of a wild animal, penance for three years because this is devilish.”

Proof that animal disguise has been popular in Europe for a long time. Whether these traditions grew out of the behaviour that was bothering the Archbishop, is another question, along with how long before the 6th century such practices had existed. But since Christianity was still far from being the only game in town in 6th century England, it’s likely that the practice of animal disguise was an old one, whether it was Saxon, Celtic or something else. I’m not even going to speculate on the purpose or meaning of these early customs. I also have doubts that The Old Horse is a direct survival of a pre-Christian ritual, even if I may quietly wish it was!

Like other mumming traditions, The Old Horse has a death and resurrection theme but instead of a human, it’s the horse, itself, which dies and is revived. In some traditions, like Richmond, in the video below, the song is sung while it’s acted out. The horse just crouches down quietly for a moment and is told to “get up” again, at the appropriate moment in the song. I’ve read of an earlier version with a play in which the horse has lost a shoe. A blacksmith is called to shoe it, which the horse resists, but the job is done wrong and the horse dies. Then a farrier is called, who revives the horse with medicine. I don’t know whether that version still exists.

When I watch this video, my thoughts are mixed. The singing is wonderful and adds to the festive midwinter feel, but I find the beating of the horse a bit disturbing, even though it’s just an act. My thoughts turn to peasants stoning hapless donkeys to death in remote Iberian villages, but I suspect that’s a false analogy. In scapegoating, there is rarely any hope of resurrection. In the 19th century, this tradition was a bit of fun and a way to get extra cash and beer. Like The Derby Tup, a similar tradition involving a ram’s head and a mock sheep butchering, perhaps it was also a way of coming to terms with the ever-present reality of the short, sometimes brutal lives of animals, that country people dealt with.

The teams soon got to know which houses were best to visit, and where they would be unwelcome. There is no evidence that the participants thought that their custom was magical or Pagan. They would have all been nominal Christians in the 19th century, and perhaps even pious ones.

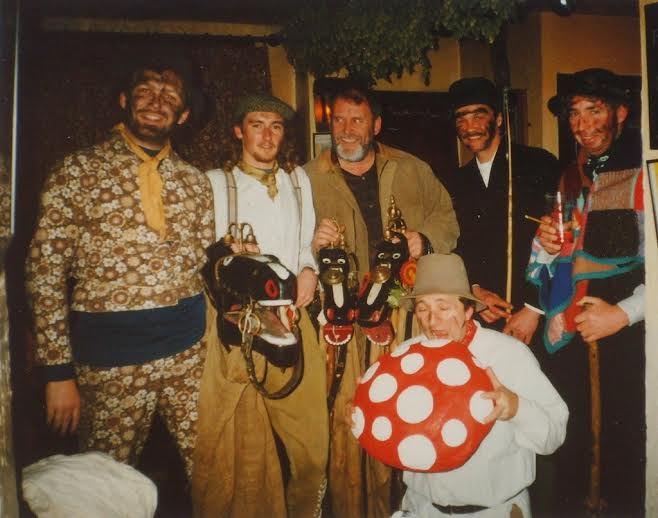

Whatever Pagan-ness that we sense bleeding through these customs is not what motivates most of the current participants. Most of them will tell you they just enjoy doing it and would hate to see it die out, and although their rhetoric often includes the idea that their tradition “goes back to Pagan times”, they rarely sound all that convinced. Dave Mooney, who founded the modern team in Kimberley, Notts. told me:

“I think that the horse may symbolise the season – he’s old and ready to die, just like the old year – but I don’t attach any religious significance to that.”

However, his passion and commitment to the tradition is typical.

“It was my idea to revive the custom. I was quite young at the time, and stumbled on it, accidentally, in a book. I persuaded some friends to help me. I helped to make the first incarnations of the horse (from wood, papier-mâché and chicken wire), and financed the buying of a horse’s skull for the current version. Dobbin is currently stabled in my bedroom.”

Meanwhile, in Kent (England’s extreme SE corner) is the tradition of Hoodening. The name comes from the “Hooden Horse”. The “H” is often dropped to make it ‘ooden ‘oss and ‘oodening. This tradition also has a lot of singing associated with it — even carol singing and sometimes handbells. Written references to it go back to the mid-18th century, and although individual villages may have gaps, or periods when their horse “slept” for a few decades, it is still going.

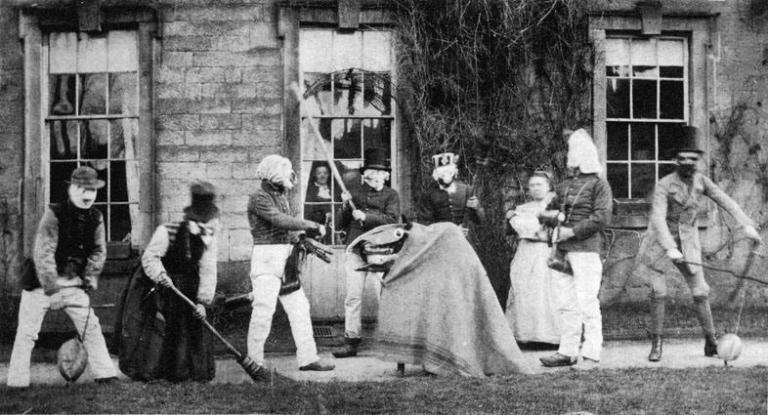

In the 19th century, and probably before, the Hoodeners were usually men and boys who worked with the horses on larger farms. The horses were generally turned out over Christmas, giving the men free time, which some of them used to take the horse ’round to other farms or villages. As far as I know, there was no play associated with Hoodening at that time, and no death and resurrection element, although there was still likely to be a groom or wagoner to lead the horse, a man in drag, possibly a “boy” or jockey, and other stock characters.

The party would arrive and sing songs, the horse typically chased the women, especially servants, and often frightened the children. There would be a lot of joking and “horseplay” and the jockey or some of the onlookers might try to mount the horse. Sometimes the onlookers tried to pull the jockey off the horse, instead. The Hoodeners would be given beer and maybe cake or money before they moved on to their next visit.

Unlike most traditions, which usually have a real horse or pony skull for their horse, the Kentish tradition is to make the horse head out of wood. Although they vary, the style is still distinctive, and can also be just as scary, I think.

In modern times it has become more usual to do a play of some kind. At St Nicholas-at-Wade, a village with a long tradition of Hoodening, a new play is written every year, with references to both local and global events worked into the script, and someone dies and is revived. At Whitstable singing is more important, and the play Is more a case of ritualized horseplay with a few lines of dialogue.

Hoodening became pretty rare from the start on the First World War until after the Second, but in Kent they prefer to view that as the tradition just having a little rest, and it is interesting to see how it clawed its way back to popularity again as different groups in different villages decided it was time to bring the horse back into use. “George” of the St Nicholas-at-Wade group spoke to me about it this way:

“In the year I was born [1966], Dobbin started his horseplay in the village again after his nap, and our family has been involved since that year – so I would have been in the audience of course since then, and probably played my first part in it in around 1977.”

George is one of the musicians for the group, but occasionally takes on a role as one of their herd of three horses, which are stabled at his house. He obviously has some deep feelings for them.

“One thing that feels quite special is to carry the horse home at night, particularly on the last night – just me and him, alone in the world, the pub’s normally closed, the village asleep, and (partly no doubt thanks to the beer) we feel invulnerable – even if a car did come, we’d walk in the middle of the road, because it’s our village, we (collectively) have been here centuries longer than those iron horses or other newcomers.”

“We’re also incidentally adamant that the horses (now) are nobody’s possession, they belong in the village, they belong to the village, they live here. If the house caught fire, Dobbin would probably be the first thing I’d rescue.”